When Steel ruled behind Iron Curtain

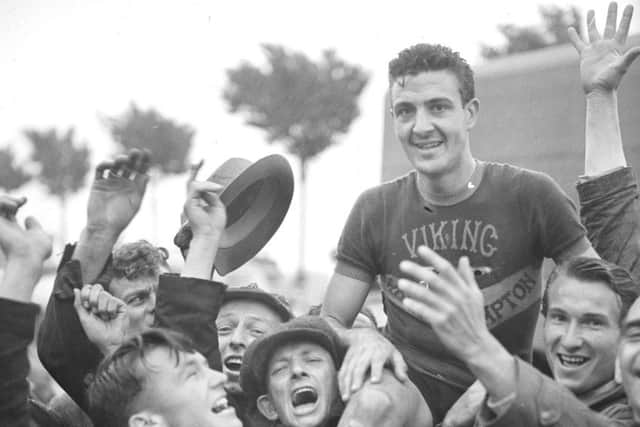

His name is Ian Steel and it is 60 years since he started the Tour de France as part of the first British team to be invited. It would prove a bitter experience, one that he says “definitely” contributed to him quitting soon after. Which is a shame, because Steel, only 26 in 1955, 86 today, was a huge talent: the winner of the first Tour of Britain in 1951 and, a year later, of a race that rivalled the Tour de France for crowds, toughness and prestige, albeit on the other side of the Iron Curtain: the Peace Race, from Warsaw to East Berlin to Prague.

The roads were bad, the riders were strong and the organisation was not especially keen on a westerner winning. Yet win is exactly what Steel did. He remains the only English-speaker ever to do so.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSteel was oblivious to the politics – there were enough of those at home, where his sport was riven with factions and disputes. He lived to race his bike: it was all he had wanted to do as a kid in Glasgow and Dunoon, where he and his sister lived with their grandparents after being evacuated from the city in 1939.

The 1952 Peace Race covered 2,135 kilometres in 12 days but first it necessitated a trip to the Polish embassy to apply for visas and to hear that, if anything happened, they would be on their own. In Warsaw the British team was introduced to Marshall Rokossovsky, the commander of the Soviet forces in Poland, who stood sternly behind his desk, meeting the teams one by one and addressed him as he knocked back a glass of vodka. Not knowing what they should say to the commander, Steel’s team-mate Bev Wood suggested the British team address him with: “Bollocks.”

“We said ‘bollocks’, with military precision,” Steel explained a few years ago in an interview with Rouleur magazine, “to the most dangerous man in Poland.”

Before vast crowds the riders were waved off from a national stadium adorned with enormous portraits of Communist Party leaders and Stalin.

“A mind-blowing spectacle,” said Steel. “Bands, marching, flags, Stalin everywhere. At the end, they released a thousand white doves into the skies above Warsaw.”

Steel rode into contention as the race became more gruelling. The Czech rider Jan Vesely held the yellow jersey until a tough mountainous stage to Chemnitz where Steel and two of his British team-mates went on the rampage, putting nine minutes into the Czech.

On the final stage, into Prague, Steel wore yellow but Vesely hadn’t given up. “He was two-and-a-half minutes down on me and the team said, ‘Sit on his wheel,’” Steel recalls. “I said, ‘That’s not very fair.’ They said, ‘You sit on his wheel or else.’

“Vesely tried everything into Prague, his home town. He tried a couple of times to break away and then the French-Pole, [Jan] Stablinsky [a future world road race champion] took off and I chased.” Steel had ignored his team-mates’ instructions; Vesely counter-attacked, and Steel, with the help of a team-mate, had a difficult job clawing him back. He spent the rest of the stage glued to Vesely’s wheel to enter Prague’s Strahoy Stadium, where 220,000 people were waiting, as the overall winner – he also led the best team. It wasn’t a popular victory. “When we finished the different stages there was always a lap of honour,” Steel says. “But when we got to the finish there was no victory lap, nothing.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe prizes were unusual. “Oh, we got radios, briefcases, statues. And a bike – I gave that to the correspondent of the Picture Post, who followed the race around.” (Legend has it that he was a fellow Scotsman who lived in Prague.)

A couple of weeks ago, Steel was the honoured guest of the Ayr Roads Cycling Club for the 50th and final edition of the Davie Bell Memorial Road Race. Steel turned up with his wife of 62 years, Peggy, who possesses the same exuberance as her husband.

Within minutes of meeting, he tells a story about their first encounter. She was the sister-in-law of his mechanic at the Viking professional team, Bob Thom, with whom he stayed in Wolverhampton. Steel recalls Peggy entering the living room wheeling a bike, asking: “What do you think of my frame?”

“I liked her frame very much,” Steel laughs now as Peggy rolls her eyes. “Did he tell you it took him six months to kiss me?” she responds. “I wasn’t interested. Wasn’t interested at all.”

These days, the couple live in Largs. But since that first meeting they have had itinerant lives: France, Spain, Majorca and Gibralter, then across the Atlantic in a yacht and years touring the American continent in their 43-foot motorhome. They arrived in Ayr with their long-time friend, Margaret Fairbairn, who recalls that after losing her husband in the late 1990s she called the Steels to ask if she could visit. “They said they were in Halifax,” says Margaret. “Halifax, Canada.”

“But we were on the move,” says Ian. “We were always on the move.” By the time Margaret caught up with them they were in Florida. But not for long, because Peggy fancied Alaska.

This all came after Steel’s career as a pioneering, hard-as-nails bike rider: as fiercely determined as he was – probably to his cost – independent-minded. Although he competed in a golden era on the continent – Fausto Coppi, Ferdi Kübler, Louison Bobet and Hugo Koblet, who was a team-mate, were all contemporaries – he was unfortunate to ride at a time of political turmoil for the sport in Britain, with different governing bodies at loggerheads and the riders caught in the crossfire.

It all came to a head at that 1955 Tour de France. Steel was selected for a British team that was the national squad in name only – in fact it was listed in the official team programme as ‘England’, despite the presence of a Scotsman.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEven before they arrived in France there was wrangling over how the team should be picked. The invitation had come from the French newspapers Le Parisien Libéré and L’Equipe and so it was decided that the British press should select the team; thus, journalists from the News Chronicle, the Herald, Daily Mail and Daily Mirror named a ten-man team that included six Hercules riders. Steel rode for Viking, Hercules’s great domestic rivals (the bike manufacturers were local rivals, too: Hercules from Birmingham, Viking from Wolverhampton).

Crucially, as well as providing most of the riders, the team was managed by the Hercules boss, Syd Cozens. That was to have devastating consequences for Steel.

“Syd had tried to get me into the Hercules team but I said no, because Viking had been very good to me,” says Steel now. But the non-Hercules riders were unsure whether they were there to represent Great Britain [or England] or to help the Hercules riders, who included Brian Robinson, who a few years later would become Britain’s first stage winner.

“Seven days in,” Steel says, “I was with a small group at the front. It was the first of the mountain stages. I was doing very well, I was very fit. And Syd Cozens comes up in the car, says, ‘Ian, I want you to go back for Stan Jones’.”

“No, I’m not,” said Steel.

“If you don’t go back you’re going home tonight,” Cozens told him.

“I thought, blow it, if this is what I’m up against,” Steel says now. “I went back through the bunch, out the back, back to Tony Hoar and Stan Jones. Stan said, ‘What are you doing?’ I told him I’d been sent back to help him. Stan said: ‘But I can’t hold your wheel!’ So Tony and I left Stan and we rode to the finish and finished within the time limit. But I was absolutely demoralised.

“My soigneur, a Frenchman, said to me the next morning, ‘Take this little bottle, just when you feel it.’ I said, ‘I’m not into drugs at all,’ but I put this bottle in my pocket.” Steel’s motivation had gone. He didn’t care any more; didn’t even want to be there. He was dropped and caught by the ‘broom wagon’, the vehicle that sweeps up riders who want to give up. Before climbing into the bus he took out the bottle and poured its contents over his sprockets. “At the finish the soigneur asked what I’d done with it and I told him. He said, ‘Non, non!’ I was home the next morning.”

The British professional scene collapsed soon after. Steel spent a brief time as a team-mate of the Swiss Koblet, the original ‘pédaleur de charme,’ who rode with a comb and a bottle of cologne in his jersey pocket, but the Scot’s career ended when he was in his prime. “Definitely!” he exclaims when asked whether he could have achieved more as a cyclist.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut he didn’t seem to dwell on that. He took up sailing instead. For six months of the year he and Peggy ran a B&B that subsidised their travels for the other six months until Ian’s throat cancer forced them to examine their priorities. Peggy said that if the treatment didn’t work they should take off. Then she said: “Why should it only be if you’re not cured? If you are cured let’s clear off anyway.”

He was given the all-clear, and thus began the life of adventure that only ended when Steel felt pain in his throat again and returned for treatment – and stayed. He relates all this cheerfully, without a trace of bitterness. The impression is of a man who – in tandem with Peggy – has lived life to the full. It was how he approached racing, he says – full on. “Oh, I had tunnel vision,” he says. “All I wanted do do was be a good bike rider.

“Which,” he adds, “I proved.”