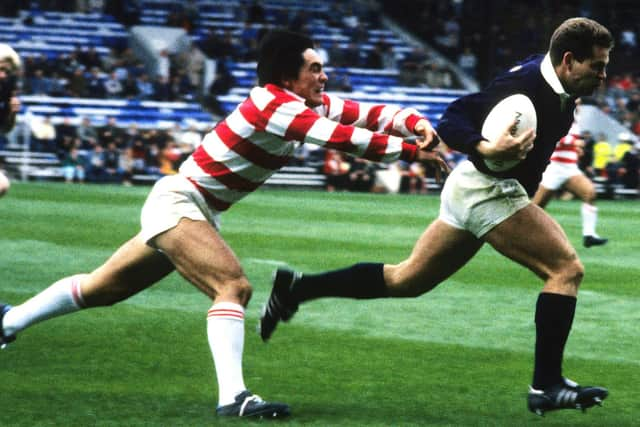

Scotland's Matt Duncan on beating Romania behind Iron Curtain and how resilience learned from rugby is helping him battle MS

This was 1986 when Romania was under the somewhat less than benign dictatorship of Nicolae Ceausescu and the order with gun at the ready to close the window blinds for landing – the opposite of normal – was the first indication that Bucharest would be a trip like no other.

It should be said that Duncan’s is a rugby story unlike many. We’ll cover the lot, including his ongoing battle at 64 with multiple sclerosis. First, though, from the former dark blue winger’s front room in Milngavie, East Dunbartonshire, some more memories of rugger under communist scrutiny: “The guard on the plane also warned us that photography was forbidden. Every soldier we saw after that had a machine gun and a big, slavering dog so no one was going to argue with that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We’d been told by guys who’d played in Romania before that our hotel rooms would be bugged and I’m pretty sure they were. When we trained there was a line of troops the length of the field, some of them just boys, wearing uniforms three sizes too big. And we couldn’t socialise because of a curfew.

“We’d come with our own food but all but one of the hampers disappeared. The department stores had fancy window displays although inside they were empty. Romania seemed like a really poor country so the soaps, lipsticks and cigarettes we’d brought to give away went down well. The match, though, was very important to Ceausescu; he wanted a victory for national prestige. I guess it was an example of what we now call sportswashing.” But the tyrant ruler didn’t get his win, Scotland triumphing 33-18.

However, if Bucharest was an unsettlingly weird place to be playing rugby then the very idea of Duncan ending up with an oval ball in his hands was equally strange. He says: “I didn’t take up the game until pretty late. But, first time at Murrayfield aged 15, I was watching all this mayhem and thinking: ‘This is fun!’ And just then my school, Douglas Academy, which until then had only played football, started a rugby team.

“I was tried at stand-off but, not being a footballer, couldn’t kick. Centre was no good because I couldn’t pass. Then full-back; ach, dropped it again. Couldnae catch either! There was only one position left and because I was a bit of a runner was sent out to the wing. If I could keep the ball in my hands, maybe that would work out.” A bit of a runner? Our man is being unnecessarily modest; he was a national schoolboy champ at the esoteric 300m hurdles.

But maybe the most surprising thing about Matt Duncan, Scotland flier, 18 caps, seven tries including scores in every group game at the inaugural World Cup and in our biggest-ever walloping of England, is that he’s not really Matt Duncan.

Born in Milngavie to English parents, he began life as Matthew Fletcher. Then, when he was just two, Harry and Margaret split up. Harry returned to his home city of Leeds and the couple’s only child remained here with his mother but in his young life suffered something of an identity crisis. “Fletcher is an English name and Mum had an English accent so from other kids I got: ‘You’re English, you’re English.’ It was teasing but it was irritating. It was also an insult to my mother: a teacher and a wonderful woman. When she remarried, became Duncan and asked if I wanted the same name I was pleased. But that’s where the driving ambition came from. My attitude was: ‘I’ll show everyone that I’m Scottish by birth and by choice.’ I was going to play rugby with a thistle on my breast.”

First, out on the wing, there was the nascent Douglas Academy XV. “We didn’t last terribly long because one of our number was caught smoking on the bus. Just before that there had been some gambling, card games for money. Aye we were a pretty wild bunch.” Duncan graduated to West of Scotland but his introduction to Burnbrae wasn’t auspicious. “An older lad from school, Graham Robinson, got me and the boys into the clubhouse, showed us the big bath which was definitely impressive, but what we really wanted was beer. Being underage we were to wait in the far changing-room. Graham came back with a tray of pints but just as we were getting stuck into them Jimmy Dinsmore, the club president, turned up at the door. He ordered us to pour the lot down the plughole.”

Allowed back, Duncan would hang around the pitches on Saturday afternoons and if the fourths or fifths were a body short he’d get a game.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThen as a uni student based in Crewe he’d travel up for what by then was his regular shift on the flank. “I’d like to tell you it was all for the love of rugby but sex and money were involved, too! I had a girlfriend in Glasgow and would stay over with her. And West gave me 20 quid for the train but using my student railcard I was able to pocket a fiver.”

Life was good for the young man, his trademark moustache sprouting nicely, but what was that strange feeling in his legs? “There were these dead areas. I first noticed them when I was 18 or 19. My poor dad contracted MS and died in his forties. But I didn’t worry. I didn’t get myself checked out. I thought if there was anything wrong it was just going to get in the way. Nothing was going to stop me playing rugby.”

Duncan’s international debut came against France at Murrayfield in 1986. “I roomed with Gav [Gavin Hastings] and rode on the bus to the stadium with Soley [David Sole]. It was their first game, too. I don’t remember much about it because everything happened so fast. But we won by a single point [18-17] and I was bursting with pride.”

Every player takes a different path to their first cap; Duncan’s had been hectic, both emotionally and physically. There was the family break-up. The doubt over who he was. The doubt over whether he’d be any good at a sport which at first hadn’t interested him. The death of his father. Those funny twinges. “How the hell did I get here?” he must have asked himself that day, not least because if it hadn’t been for the orthopaedic surgeon to whom he’d gifted match tickets, Duncan probably wouldn’t have been on the pitch.

“Jimmy Graham, a wonderful man. I’d been in a cast for two years because of a complicated ankle injury. Jimmy had to use part of my achilles to hold the tendons in place, an operation he’d never performed before. Then at the start of my comeback season, when I was determined to push on and become a Scotland international, I shattered my collar bone. It was broken into three bits and I needed a bone graft from my hip. Jimmy to the rescue again.”

A few weeks after France, England came to town, Duncan diving for our first try in the never-bettered 33-6 thrashing. The team featured the brilliant talents of John Rutherford and Roy Laidlaw who’d won a Grand Slam, allied to the likes of John Jeffrey and Finlay Calder who’d claim the prize later. “England had a reasonable set of guys but they were full of themselves, which has always been their downfall. Our coaches Derrick Grant and Ian McGeechan had pinned stories from the papers on the dressing-room wall about how they were going to hammer us, Duncan couldn’t catch, this fool couldn’t tackle – basically rubbishing our team. John Beattie announced that as soon as the whistle sounded he was going to whack Wade Dooley, and he did. This was the Glasgow gang culture equivalent of taking out the big man, the leader. Game bloody on!”

In the 1987 World Cup in New Zealand Scotland met Romania again, bettering the previous score and crossing for nine tries and 55-28. Tonight Duncan will watch with wife Sharon from the front room in Milngavie hoping for another romp. “The team cannot be thinking ahead to Ireland. I’m of the generation which never lost to the Irish but we must win this game first, and win it well. The performance against Tonga was good but still probably 20 points short of what it should have been.”

His final appearance came in 1989. A dad of two and grandfather to four, Duncan has retired from a fulfilling job in local government helping the most disadvantaged find employment, on top of 20 years as a volunteer for the Children’s Panel looking out for waifs and strays. Some challenges may be over but MS is being faced with his usual fortitude and humour.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Not long after I finished playing I got paralysis in my arm. I couldn’t understand what was wrong and was very disappointed because I was drinking a glass of wine at the time! I went for tests which were inconclusive, and that was fine because I didn’t want a diagnosis.

“MS isn’t hereditary but I remember how it affected my father. When I went to stay with him in the school holidays, six or seven years old, he was unsteady on his feet and I was seen as the poor kid with the drunk man. Folk would tut-tut in the street and I wanted to say: ‘He’s just slipped!’ I didn’t know he had MS but he deteriorated from it quite rapidly.

“Really, I barely knew him. He was cut out of family photographs. Even ones of Mum on their wedding day. Different times and I guess that was how divorce was viewed back then. It was sad but I was young and with people who were looking after me. There was nothing I could do to change the situation.”

Duncan has a connection with his father now. It’s unwanted but he’s determined to stay positive. “Maybe it was idiocy to not want to be told I might have MS but I believe that attitude can get me through this. Things will get worse, I know, and it really is a bitch of a disease because it can get you in all kinds of places. So far, though, I consider myself lucky. My eyes are okay and I can swallow my food – some folk struggle and also have trouble speaking. The fine motor skills are a problem – I can’t use a pen or a screwdriver. But I can walk a mile and a bit unaided and leaning on a golf trolley I can play nine holes. I thank all my rugby coaches over the years for teaching me resilience. It’s the game that’s helping me get through this. And I will, I have to.”

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.