Aidan Smith's Saturday Interview: Welsh wizard John Taylor on one of rugby's great contests, Bill McLaren, standing against apartheid and his worry that Scotland are "building something".

“I’m in Edinburgh’s Corstorphine Road with Bill McLaren,” he begins. “My first-ever game in the commentary-box and it’s alongside the master. Bill said: ‘Will you walk to Murrayfield with me, son?’ So of course I did. The streets were bobbing with red and white scarves and hats, as they always were for this fixture. But there was panic in the air. It was the first game to be all-ticket after the 100,000-and-then-some one [1975, world-record attendance] and most of the Welsh hadn’t realised this. ‘Any spares, John?’ they asked me. ‘Can I hold your notepad?’ But then a beautiful thing happened. Some supporters knocked on the door of a house and explained their predicament. They were invited in to watch on TV. They were copied by other fans who tried further along the road and got lucky too.”

Taylor, the Grand Slam flanker, cites another example of the thistle-leek communality and fraternity: “I’m finished up playing and am a hack reporting on rugby, back at Murrayfield for the Calcutta Cup. England win and I’m riding in a taxi to the airport. The cabbie thought I was English. ‘You’ll be pleased,’ he said. I said: ‘I’m neutral - Wales.’ ‘So do you know Ystradgynlais?’ he said. ‘I do,’ I said, ‘the little place in the Swansea valleys, but how do you know Ystradgynlais?’ He told me how a few years before these Welsh guys had come to Edinburgh on the ‘killer’ - the rugby special which travelled up and down from Cardiff on the same day - but after so much merriment they couldn’t face the train home. They’d had a good win at the bookies so stopped my cabbie in Princes Street and asked him ‘How much to Ystradgynlais?’ This would have been long before sat-nav but off they went. He couldn’t face driving straight back and so was put up for the next night. A solid friendship was formed. He’d been back there every other year since, enjoying Welsh hospitality, then being the host when the game returned to Edinburgh.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

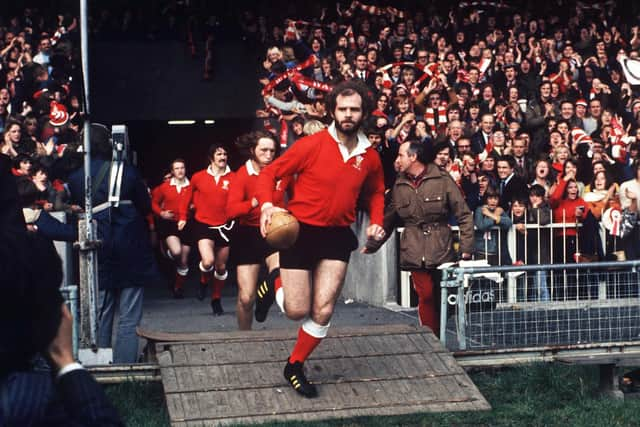

Hide AdAnd out on the park Scotland vs Wales hasn’t been too shabby down the years. If you never saw Taylor’s Red Dragons they were the Barcelona of rugby. Gareth Edwards and Barry John mesmerised crowds - and drunk-seeming opponents - much like Xavi and Andres Iniesta, and maybe our man was the Sergio Busquets of the team for his power and relentlessness, with the closest to a Carles Puyol hairstyle. Scotland strove manfully to match them, not least in Murrayfield’s 1971 blockbuster, but Wales en route to a Grand Slam won 19-18, with that steepling kick from way out wide by Taylor confirming the match’s status of a solid-gold classic.

We’re speaking via Zoom, Taylor in the memento-crammed study of the home in the Kent village of Goudhurst which he shares with his wife Tricia, a former couture model. And what a story these walls can tell. He was an All Blacks-vanquishing Lion. At the mic he described World Cups, also Olympic Games. There was the time he stood against apartheid and feared banishment from the game. And the time rugby almost killed him.

Now 75, the wild hair which got him nicknamed Basil Brush has long gone, though a giant plaster of Paris statue in the corner of the room doesn’t exaggerate its voluminousness. No, the style wasn’t borrowed from any particular progressive rock drummer, though as a teenager he did play in a band.

The accent which fooled that cabbie comes from having lived all his life in England, first in Watford, his parents having met at “the local loony-bin” – as members of staff, he adds. A younger brother followed football but Wales was the land of Taylor’s father, and his mother, so he favoured the egg and wore the flaming red shirt for the first time at Murrayfield in 1967, an 11-5 win for Scotland.

“It passed in a blur, although you don’t forget that you played against Jim Telfer. This was the era of proper rucking when Jim would come off with his back covered in gouges. No one could shift him.

“I was 21 and probably not quite ready for international rugby. Playing for London Welsh we had a crazy festive schedule: Neath on Christmas Day, Llanelli on Boxing Day, Swansea the day after. In the first five minutes of the second match I got kicked in the head by Byron Gale. I’m sure the big bandage I had to wear helped me get noticed by the Wales selectors and for the next ten years, every time I bumped into Byron, I thanked him.

“Then came the trial: the Probables vs the Possibles, or Impossibles as I called my lot. I was up against Omro Jones – Om the Bomb – and doing well, so at half time we were swapped on the pitch, me joining the Probables. ‘You’re only borrowing that shirt,’ said Omri, who wasn’t happy.” Taylor would win 26 caps and, but for his stance against South Africa, it would have been more.

“Back in ’67, international rugby was pretty primitive,” he continues. “Living in London, working as a schoolteacher, I flew up to Edinburgh by myself and didn’t meet the rest of the team until training 48 hours before the game. Gareth Edwards, Barry John, Gerald Davies and Dai Morris were all new like me. But our selectors were an unforgiving bunch and, having lost every game that season until the final one, if we hadn’t beaten England you might never have heard from us again.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNext time at Murrayfield in 1969 Wales were the victors. Mervyn Davies - Merve the Swerve - was the newbie, nervous as a kitten, until Taylor took him on to Princes Street where he felt right at home. Edinburgh was an expedition for the Welsh hordes, an adventure. Twickenham, a shorter trek, allowed for fewer ruses, less dallying, less fun, all summed up in Max Boyce’s comedy ditty “The Scottish Run.” Plus, down Twickers way there weren’t many miners with which to bond.

As a teacher, Taylor started out in PE, switched to History and became deputy headmaster at Elliott School in Putney. So how did coping with 2,200 kids at an inner London comprehensive compare with squaring up to a growly opposition pack? “Probably tougher. I had pastoral duties, different from those at a private school, because once a month I had to be in court with the rowdiest pupils, up on charges of theft and suchlike. But I loved that school and it amused the kids that they could see me on telly, getting knocked about a rugby field.”

Between these two Murrayfield clashes Taylor became a Lion, although the ’68 tour to battle the Springboks caused him much torment. “I was obviously aware of apartheid beforehand but, desperately wanting to play for the Lions, I bought the line about how rugby was going to ‘build bridges’. “Before we flew out the South African High Commissioner in London told us: ‘You won’t understand our politics so don’t get involved. But our rugby and our girls are great so go and enjoy them.’ I got injured in the very first game, came away from the rest of the guys while I recuperated and couldn’t really avoid seeing how the black population were being treated. I remember being left in Cape Town while the team were on the high veld when this guy was kicked off the pavement. Me going to help him just made the whites even more hostile. It was appalling. Back in Putney my school was every colour, every creed. Witnessing that assault, and hearing Afrikaners defend apartheid, was in huge conflict with what I was trying to do with my kids.

“Then in Johannesburg I hooked up with an old school pal who’d come out to South Africa for his Masters degree and got involved in the protest movement. We were at a jazz club which was illegal because the band were mixed. It was raided and the pair of us had to escape over the rooftops.

“I thought: ‘Better not tell [Lions manager] David Brooks about that.’ But it was obvious to me that apartheid was growing and our presence there couldn’t do anything to change things. I was troubled by what seemed to me our game’s arrogance. The attitude was: South Africa played rugby so therefore they had to be good blokes. What, the brotherhood of rugby overrode the brotherhood of man?”

The next Lions tour after the New Zealand triumph would be South Africa again in 1974 but Taylor made himself unavailable. Before then he informed the Welsh Rugby Union he didn’t want to play the Springboks when they came to Britain and Ireland in the winter of ’69-’70. His stance got him into bother. “I was told by a couple of England rugby officials that if I’d been English I would never be allowed to play international rugby again.” In the Principality, too, they weren’t happy with him. “There was no issue with my Welsh team-mates for we respected each other’s decisions. But [all-round Wales sporting great] Wilf Wooller, a hugely influential figure, became my arch-enemy. He disapproved of the anti-apartheid protests when the South Africans toured and we had lots of arguments on TV.” Taylor had been reassured by the WRU that being a refusenik wouldn’t affect future selection, but it did. “I thought I was done, career over. The team went on a poor run, though, and I got back in.”

Taylor is heading to the Millennium Stadium today, hoping the Dragons will stir, but is fearful that Scotland are “really building something”. His only game against us in Cardiff was at the old Arms Park in 1972 when he helped bundle Gareth Edwards over the line for the latter’s first try and then, along with 13 team-mates and some of the Scots, watched in awe as the scrum-half, needing no assistance, sprinted almost the length of the pitch and dived face first into red mud for his second.

Incredible as that score was, though, it generally rates as Edwards’ second greatest-ever – topped by the one for the Barbarians against the All Blacks a year later. Taylor, at the peak of his powers, should have been on the pitch that day. "I was a Baa-Baas type, a ball-playing forward. The brief had been to recreate the '71 Lions side but even though I played all four Tests in New Zealand I was the only one not picked." This was at the decree of Barbarians president Brigadier Hugh Llewellyn Glyn Hughes who labelled Taylor a "Communist", leaving him “bloody furious”. What a shame, I say, so he missed a stupendous game and a stupendous try – it could have been him and not Tom David sending Gareth flying for the line with a slightly forward pass. “I know,” he laughs, “although if I’d been playing I would have been that bit quicker and not needed to make the slightly forward pass!”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStill, he’ll always have ’71, Scotland very nearly ruining Wales Grand Slam until Gerald Davies’ late, late try and, as it was hailed, “the greatest conversion since Saint Paul” from Taylor. “It was death or glory. I just kept telling myself not to overkick and remembering that I’d hit two from a similar position against England - the sort of stuff which nowadays you’d pay a sports psychologist for. Thankfully it was glory.”

Though his last cap came a few weeks after another defeat at Murrayfield, Taylor continued playing for London Welsh for another five years and was exceedingly grateful for every game and indeed every breath. “One time playing Bath I tackled this guy and pulled him down on top of me, like I’d done a thousand times before, only someone jumped on him and a stray knee became a sledgehammer, smashing my jaw in about six places, plus my skull and cheekbone. Fortunately I wasn’t knocked out because the ambulancemen reckoned that might have caused me to drown in my own blood.”

It was while recovering after a nine-hour operation when Taylor took that stroll with Bill McLaren and following his debut in the commentary-box with the BBC the great Hawick oracle would, without realising, play a part in his protege becoming the voice of rugby on ITV.

“We’re at Twickenham, Calcutta Cup, it’s just ended, and the Beeb decide they want a post-match interview. There was no on-site studio, just a big old basher light shining on the gantry at the back of the West Stand. Bill nudged me looking anxious. ‘They want me to do an interview,’ he said. ‘I’m a commentator. I don’t do that. Could you?’

“I did because Bill had always been so generous to me and when ITV got involved in rugby for the first time they remembered how I didn’t completely muck up that opportunity. But it’s Bill’s excuse which makes me chuckle even now. ‘John,’ he said, ‘if you fill in for me I won’t miss my plane and have to spend another night in this godforsaken place. I can be back in the Borders enjoying the best fish and chips by nine o’clock!’”

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.