Remembering Joe McGhee’s 1954 Empire Games triumph

Proof that this achievement was born of a sensible plan to pace himself came later the same evening on the dance floor at the Closing Ball, where the Scotsman demonstrated he still had energy left to burn.

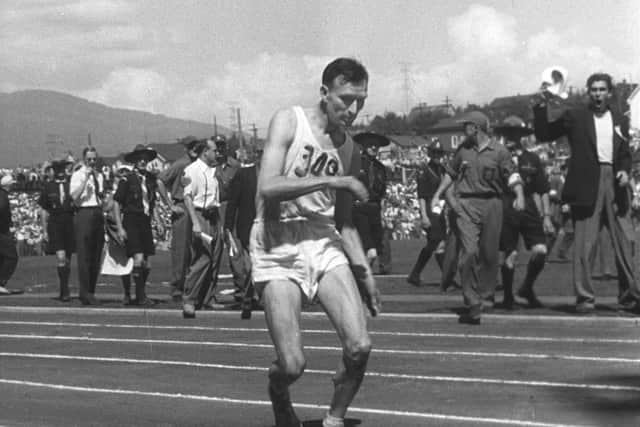

Earlier in the day, McGhee, who has died at the age of 86, earned Scotland’s first gold in the last event of the Games. Although the race is well-remembered, it is not because of the victory secured against the odds by the then 25-year-old McGhee, in sweltering conditions.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRather, the race regularly crops up in features chronicling the greatest mishaps in sport, alongside Devon Loch’s collapse at the last fence and Don Fox’s missed goal-kick in the final minute of the Challenge Cup final. However, in this case, the word “mishap” does not sufficiently convey the tragedy that so nearly befell Jim Peters, the English long-distance runner who had set four records for running the marathon in the previous two years.

Perhaps emboldened by his status as favourite, Peters, from Hackney, shot to the front. By the time he reached the stadium, not only was he in first place, he was leading the field by what some reports estimate was a time of 17 minutes. But, to the horror of those looking on from the bleachers in the old wooden stadium, Peters started to wobble.

Even now, images of him keeling over again and again, “like a drunken vaudeville tumbler” according to one report, are fixed on the mind, more so than McGhee’s impressively spritely dash to the finish, in a time of two hours 39 minutes and 36 seconds. Peters is allowed to stumble on before finally collapsing, yards from the line. McGhee, meanwhile, strides to victory, a protective cloth around his neck helping shield him from the merciless sun, in temperatures that reached nearly 30 C.

But how many recall that it was a Scotsman who took gold that day? Accounts of the race centre mostly on the admittedly dramatic denouement experienced by Peters, who never raced competitively again. Indeed, it was only in hospital the next day, when McGhee visited the ailing Peters, that the Scot truly comprehended the seriousness of his condition.

This is one reason why McGhee so rarely spoke about his success, although he did record his own memories in a diary, an excerpt from which was published by Scotland on Sunday in 1994. Many myths exist, including the story McGhee himself had collapsed on a kerb-side before being urged on by a watching old woman, a Scot, who demanded he got up, “because the honour of Scotland was at stake”.

Not so, wrote McGhee. He had simply run a more pragmatic race than his rivals, who, as well as Peters, included another Englishman, Stan Cox. “And then he even had enough energy to dance at the Closing Ball until 1am, before getting up at 6am the next morning,” his son, also Joe, confirmed yesterday.

This was one of the tales he used to hear from his father while they completed 12-mile training runs together in Aberdeen, where McGhee moved to take up a position as a linguistics professor at the Aberdeen College of Education. He previously worked in schools in Stirling and Dalkeith.

Joe junior was blessed. While he got to hear about the time his father earned a gold medal in such strength – and mind-sapping circumstances, few others did. “He was a modest man, he kept much to himself over the years,” his son said yesterday.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOthers are now left to do the talking on his behalf, including Lachie Stewart, the former Scottish distance runner who won gold in the 10,000m at the 1970 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh. This feat was acclaimed in the way McGhee’s was not. Stewart yesterday described McGhee as “one of Scotland’s true athletic greats”. The fact the Peters saga overshadowed his victory was, according to Stewart, “unfortunate”. McGhee was, however, an influential figure. “His name cropped up often in conversation, maybe not so much in the generation of today, but certainly in my generation,” said Stewart.

There was never personal ill-feeling felt by McGhee towards Peters. It is the media whom he cautioned, deservedly, for dredging up his rival’s collapse “with monotonous regularity”. In fact, McGhee and Peters, who died in 1999, would later meet up on occasion, once at the request of legendary BBC broadcaster and former rugby international Cliff Morgan. “Peters did acknowledge at the end of the day how sorry he was dad did not get the recognition,” said Joe yesterday. “It’s interesting to hear them both speaking together on the radio, recalling what happened so many years earlier. My dad did visit him the next day in hospital – he was one of the few people who got in to see him.

“Peters at the time was so dehydrated it was touch and go whether he would pull through. There was never animosity between them. In fact, on the radio you can hear a quite touching camaraderie.”

McGhee never returned to Vancouver, the scene of what deserves to be remembered, despite all the attendant drama, as one of Scotland’s finest sporting victories. “He wasn’t much of a traveller,” said his son. Back in the early 1990s, Joe junior did make the trip to Vancouver himself, however. It proved timely. “The actual stadium was being pulled down,” he recalled. “I managed to sneak in two days before it was demolished. It was as if fate had taken me back.”