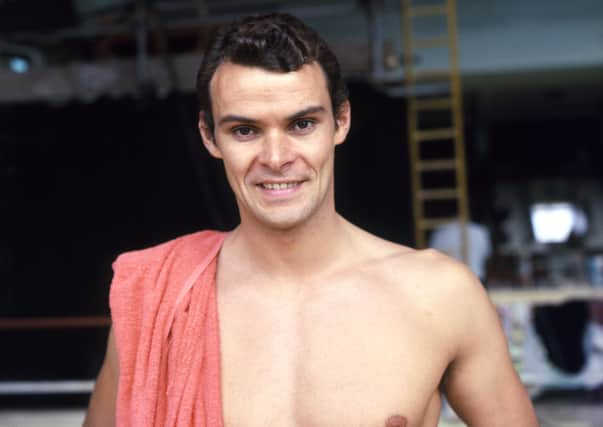

Interview: Scottish swimming sensation Bobby McGregor on how he stunned the Americans at the Tokyo Olympics

Scotland’s prince of the pool at the last Tokyo Olympics is full of sympathy for athletes denied their chance to compete in the Japanese capital this summer. “All that training gone to waste,” says Bobby McGregor. “At least that’s what some will be feeling right now.” And there’s something else which occurs to the architect in him: “All those wonderful buildings they’re not going to see.”

The world has shrunk since 1964 and people are more well-travelled than the lad from a pebbledashed council house in Falkirk who, when told he should try for the Commonwealth Games in Perth, assumed this was our fair city and not the Australian version 9,000 miles away. Still: those arenas. “They knocked me out,” he adds. “I took millions of photographs. They were inspiring to me when I was halfway through my degree. After that I wanted to design a spectacular swimming pool for Scotland.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was none more spectacular in Tokyo than the Yoyogi National Gymnasium, a stunning, sweeping, modernist icon which was the venue for the swimming and, along with others from ’64, will see action again when Covid-19 has been banished and the Olympics are-re-staged. McGregor, 20 at the time, reverentially intones the name of the man who dreamed up the Yoyogi: “Kenzo Tange.” But, under what at the time was the world’s largest suspended roof span, he wasn’t quite able to bring home gold.

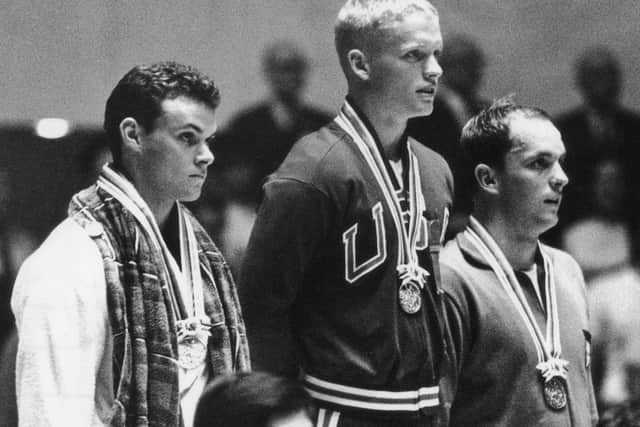

“I regret that to this day,” says McGregor, now 76. “From the moment I got back home folk told me it was great to have won a silver medal but for a sportsman who thinks he’s going to win the only thing worse than second is fourth and you’ve missed the podium completely. And I did think I was going to win. I was confident, I was cocky. I missed out by six hundredths of a second.”

The new James Bond?

Still, it was a valiant effort and what a thrill it is to be talking to the Falkirk Flyer today. Before the ’66 World Cup, before Lisbon, his 100m freestyle final qualifies as my earliest memory of sport on the goggle-box. Indeed, Bobby in the Yoyogi goes beyond sport. It’s in the general archive of monochrome marvellousness along with Neil Armstrong on the Moon, Chris Bonnington on the Old Man of Hoy and, yes, Kenneth McKellar in the Eurovision Song Contest. And the question I’ve always wanted to ask him is this: as a strapping, square-shouldered Scot of dark good looks, did he ever get mistaken for Sean Connery?

“Well, some could see a likeness back in those days. And when I had a house in America folk over there told me I spoke like him. I have to say that my wonderful agent, Athole Still, hustled for me to take over as James Bond when Sean was giving up the role. He spoke to [007 producer] Cubby Broccoli about this, telling them there was another hunky Scotsman who would be ideal. Obviously that didn’t happen!”

While Connery as Bond was greeted by Ursula Andress memorably emerging from the deep, he faced many water-based perils in Thunderball including murderous frogmen, but McGregor encountered a few of his own. Petty-minded townsfolk and their elected representatives could be a problem, even without harpoon guns.

He explains: “I trained at Falkirk Baths where my father was the manager and that was some help: he let me bomb up and down for three-quarters of an hour early in the morning before the doors opened to the general public. But I needed a bit more than that, I was going to the Olympics. Dad asked the town council if I could have a lane in the evenings but recreational swimmers complained and that was stopped. We tried lunchtimes and the same thing happened. Honestly, I don’t think you could make that up.”

McGregor’s frustrations chime with those of Ian Black, the Highlands schoolboy sensation of the 1958 Commonwealth Games whose gold-medal success at butterfly was greeted with astonishing churlishness and jealousy by his headmaster and who found his local authority just as reluctant to assist him in his bid for the Rome Olympics two years later.

“It’s not as if swimming back then was an obscure sport,” adds McGregor. “After Ian’s achievements, it had a massive profile compared with today. You hardly see it on TV anymore which is a shame because it’s brilliant for everyone’s good health. When I was coming through there were ten or 12 big meets – Scotland versus the home nations and international events – shown live every summer. I first swam for my country at 16 and was so proud. A bit later, the BBC would phone me up and go: ‘We’ve got the schedule of races here – can you tell when you’ll be competing so we know which ones to cover?’”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSwimming was amateur – in just about every sense. McGregor was rated one of the top three on the planet and the year before Tokyo, set – and twice broke – the world record in the 110 yards freestyle, Britain being one of the countries which continued to use imperial distances. But there was another setback just before the Games: “The entire Great Britain swim team was to be coached by Bert Kinnear [Arbroath-born Olympian, swam backstroke at the 1948 Games]. The Americans, though, all had individual coaches. Dad trained me normally and we asked the council if he could possibly come out to Japan for five days before my event. The cost, flights and hotel, was £2,500 but the councillors had a vote and rejected the idea.”

The Americans couldn’t believe he trained in a 25-yard pool

It should also be mentioned that Falkirk Baths were the regulation length for a UK municipal pool at that time. “My rivals couldn’t believe it was 25 yards. I didn’t think it was such a big deal but obviously 50 would have been better. The other guys just laughed. Before Tokyo I was interviewed by [American magazine] Sports Illustrated. They sent a journalist all the way to Falkirk for a day-in-the-life feature and, first thing, we met at his hotel and I took him to the pool. He was dumbfounded it was only a 25-yarder and I reckon he must have thought I was kidding him and there was a secret Olympic-sized pool round the next corner that I wasn’t telling him about. Incognito, he followed me the next day to see if I went back to the wee town baths. Of course I did.”

Robert Bilsland McGregor also won silver in Perth, once he’d realised it was Down Under, and the next Commonwealths in Jamaica in ’66. His quest for gold was finally achieved in that year’s European Championships in Utrecht. In retirement as the father of two grown-up sons he’s returned to Helensburgh with his wife Bernadette, the old open-air pool there being where he first dipped a toe in water, although he didn’t learn to swim until he was nine.

This is perhaps surprising when you consider that his father, David, wasn’t just a pool manager and his coach but an Olympian in his own right, having been a member of the GB water-polo team in the Berlin Games of 1936. “Dad was an extremely modest man and when he came to train me he was obviously keen for me to do well but not overbearing, just lovely in fact. When I found out how notorious the Berlin Olympics had been I asked him about them. Understandably, he hated Hitler’s propaganda. And he was really upset that Germany were able to re-arm after the Second World War.

“Water-polo was huge in Dad’s day – and as a Scot you had to be extremely good to get into the British team. I found this out when my mum showed me a suitcase full of his medals and write-ups. He played for the club in Motherwell who won many championships and had folk queueing round the block to see them play. But you don’t hear much about water-polo these days either.”

That Sports Illustrated piece on McGregor was a fine piece of writing, full of colour about him probably preferring fishing to swimming – indeed he’d only learned to swim to be allowed to venture alone to the Union Canal beyond the back garden in search of pike – and being given this build-up when he went back to Comely Park Primary School to present prizes: “Someone as well known as George, Paul, Ringo and John.” Much more of a Frank Sinatra fan, McGregor clearly intrigued the journalist, John Lovesey, for belonging to an “iron and coal town”, being so shy about his celebrity status and “tending the fire his mother likes to have blazing summer and winter”. But there was respect for McGregor’s times in swimming’s blue riband race and the threat he posed to Lovesey’s countrymen.

Looking ‘scunnered’ on the podium

The United States, Australia and Japan had dominated the 100m. Since the Games began in 1896 only three gold medals had eluded those countries and since the Second World War only three bronze had gone elsewhere. Yet here was the “sheer, shining novelty of a Scots lad fighting for room at the top”.

McGregor wants me to stress that when he describes the difficulties he encountered on the road to Tokyo he is not “making excuses”. This was sport at the time, in Britain at least, and there had been help for his glory bid from his university, Strathclyde, who reinstated an old pool which had been concreted over. And our man’s optimism about his chances increased when he discovered that the American Steve Clarke, who held the metric world record, had been hit by appendicitis.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe reflects on what we now call big sport and its motivations back in the amateur era: “Very few athletes had a chance of winning a medal. For maybe as many as 90 per cent it was about getting in the team and getting on the trip, travelling the world, meeting other fit young people of like mind and enjoying the fabulous parties. That was one of the main reasons I took up swimming. But then I did get a chance … ”

McGregor had not ignored the challenge of the man who would snatch gold from him, Don Schollander, but this American had little experience of the distance, his speciality being 400m. Hailing from Oswego, Oregon (pop: 36,000, on a par with Falkirk), he thought the 100 would “make or break” him for the rest of the Games. Make that make. Schollander would go on to claim four golds, the first to do so since Jesse Owens in Berlin.

“I liked to go out fast which always left me absolutely knackered during the last ten metres, when I hoped my technique would see me home,” adds McGregor. Five metres from the wall the Falkirk Flyer was ahead but Schollander produced what he admits was a “stunning finish”.

McGregor laughs as he remembers how on the podium for the medal ceremony he looked “scunnered” about the result. Back home there was a parade for him and a civic reception: “I stopped myself from mentioning how the council hadn’t let me train.” The next Olympics in Mexico coincided with his finals at uni and, struggling to achieve peak fitness while he crammed for the exams, he finished fourth. Following his father, he played water-polo for Scotland. There were appearances on A Question of Sport. He had a spell in journalism for The Scotsman and our sister paper, Edinburgh’s Evening News. As an architect he didn’t quite manage to replicate the feats of Kenzo Tange but designed pools for swanky houses. He was the go-to guy for cutting the ribbon to open new municipal baths, among them Kirkintilloch and East Kilbride, although notes with regret that some have since closed.

But there was no lack of appreciation for McGregor’s talents across the pond in the States. “The International Hall of Fame in Fort Lauderdale, Florida staged a meet every Christmas for the world’s top swimmers and I was invited three years in a row. And in ’66 there was a re-match against Schollander at his club in Santa Clara, California. Mark Spitz was also in the race and it was broadcast live on CBS. Because of my studies I was about to decline. Then Don told me Frank Sinatra would present the prize to the winner and since he was my idol that clinched it. I won but Frank didn’t show. Bing Crosby deputised and what a gent he was.”

You see, Crosby is still Crosby and a silver medal is still a silver medal.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.