David Wilkie on Olympic glory, his ‘pal’ Elton John, boarding school woes, blaming Warrender for losing his hair and why he prefers Duncan Scott to Adam Peaty

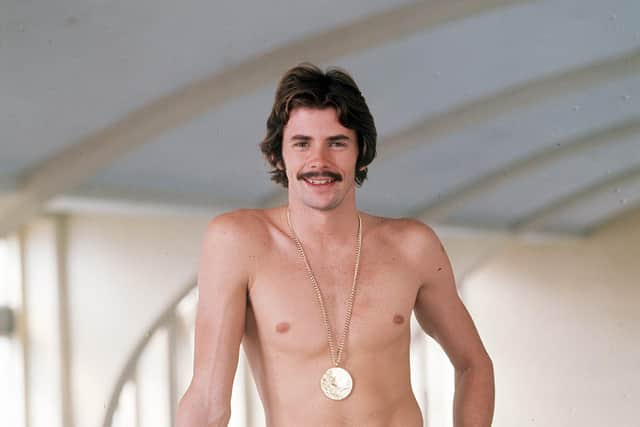

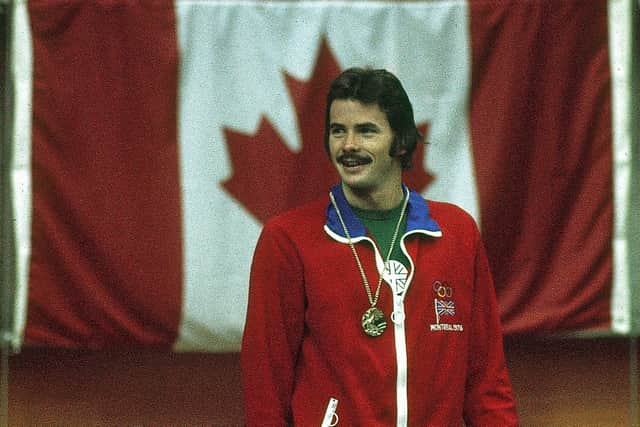

For David, in far-off Montreal, torpedo-ing his way to Olympic gold and glory? For David with that anti-streamline hair and moustache, looking more like a sensitive singer-songwriter of the 1970s soft-rock idiom? For David whose aqua-based heroics inspired a generation of Scottish weans to battle chlorine, verrucas, jettisoned Elastoplasts and the “No petting” diktat while diving for bricks in their pyjamas to achieve swimming proficiency?

The answer, chorused in households across the land, was a resounding “Yes”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhat a thrill to be snuggled up in Wynciette, dry this time, and cradling mugs of Ovaltine while cheering our man’s obliteration of deady American rivals and the world record for the 200m breaststroke. What a hoot as well ...

“For the Beeb’s harassed commentators,” wrote the great Aussie wit Clive James, reviewing coverage of the final on 24 July, 1976, “it was hard to know how to follow that climactic moment when David Wilkie won a gold medal and Alan Weeks had an orgasm.”

The doyen of TV critics then made a valiant attempt to jot down all the foaming delirium, no mean feat in the days before VCRs: “Tonight the Union Jack is raised and is being waved very proudly indeed! … A proud Scot! … And so the big moment has arrived! … The Flying Scotsman! … We have a certain gold medallist! … David Wilkie is absolutely superb! … And it’s … Wilkie!”

So what a pleasure now, with today the anniversary of one of the greatest swims of all time, to be talking down the line to the 67-year-old, at home in Surrey by his own pool and contemplating a return to his regular 20 morning lengths after being laid low by a summer cold. First question: given he was in south-east Canada making history, did he know, perhaps learning later, that he’d sent Weeks and co-micman Hamilton Bland into the throes of ecstasy?

“Yes, I did,” he laughs. “But that was a great commentary, wasn’t it? Alan was old-school BBC, like David Coleman and David Vine, and a terrific enthusiast. I found out about the Clive James crit, too, and Alan knew about it and he was such a humble man that I think it embarrassed him. But, trouper that he was, when we worked together later, speaking at various sports events, he’d make a joke about it along the lines of: ‘When you get to my age, orgasms are a cause for rejoicing!’”

The Wilkie/Weeks gold standard, then, is the challenge for those in Tokyo: Andy Jameson and Adrian Moorhouse describing the action poolside and Adam Peaty and Duncan Scott in the water. Our man will turn fan through the wee small hours, and he’ll be especially cheered if the Glasgow-born contender can inherit the “Flying Scotsman” mantle.

Says Wilkie: “I like Adam, he’s a great competitor, a tough beast - and that’s what he’s like: a Hereford bull, charging up and down the pool, but he only swims one event, the 100m breaststroke.

“I prefer watching Duncan because he’s an all-rounder like I was. I could swim all the events and held world records in a variety of them. Adam may be our most successful swimmer right now but I think Duncan is our best swimmer. He’s not the best-ever, though - that’s me.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWilkie chuckles as he says this but there’s no need for any false modesty.

British, European, Commonwealth, world and Olympic champion, all at the same time. Those best-on-the-planet records? In all, five. In Montreal, the only non-American man to win a swimming gold. A performance voted finest of the entire Games. Even now, get a bunch of wrinkled pool legends together and it will still be nominated and eulogised.

He’s been pretty successful towel-dried, too, for while Peaty may be the current swim-team’s poster-boy, Wilkie was first to hold the title. Peaty can inspire headlines like this week’s “I’ll go like flash in my tash” but has there ever been a groovier moustache than the one sported by Wilkie - on the chat-show appearances in the wake of his stunning success, on his own TV programmes such as Winning With Wilkie, and just sauntering up the Kings Road?

Once in this Swinging London thoroughfare, Elton John nodded and said: “Hi David.” The American friends with Wilkie that day were gobsmacked. He thinks back to that time: “Did I hang out in nightclubs? Yeah. Did I meet some crazy people? Yeah. It was great fun.” There were fast cars and glamorous girlfriends, including Debbie Raymond, daughter of porn baron Paul, who died of an overdose after they’d split up. “She had a lot of talent as a singer but so much money and the drugs got to her, which was a bitch.”

Wilkie would eventually settle down with Helen Isaacson, an interior designer with whom he founded a vitamins business eventually sold for £7.8 million and for the dad-of-two there have also been forays into pet food and property. Along the way, alas, his cherished thatch disappeared.

“I really loved my long locks,” he sighs. “All my American rivals had crew cuts so I was regarded as this freak.” Wilkie removed every hair from his body in an attempt to shave the odd hundredth of a second off PB but those on his head were preserved under a cap, initially one borrowed from his mum Jean, which made him stand out from the rest, as did the goggles.

He laughs: “I still remember the day, out in China and only 28, when I shrieked: ‘That can’t be a bald patch!’ I thought there had to be something wrong with Chinese mirrors. Unfortunately there wasn’t. I blame the chlorine - and I blame Warrender Baths!”

What a tale Wilkie has to tell and what careering contrasts his life had thrown up by the age of 11. Up until that moment he’d swum, purely for fun, at the Colombo Swimming Club in Sri Lanka’s largest city where he was born - a lovely palm tree-lined lido with azure blue waters just beyond. But then he was deposited in Edinburgh, snow on the ground, scratchy blankets in the boarding-school dorm - and “the worst vending-machine hot chocolate in the world, the worst soup too”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWarrender, one of the capital’s Victorian-built municipal pools, was where the journey to Montreal began for Wilkie although he certainly didn’t embark on it right away. Firstly he had to get over his homesickness. “That was hellish. I couldn’t understand why I had to leave such an idyllic place as Sri Lanka where I’d enjoyed so much freedom and swap it for this cold, closed environment. There were a lot of tears.”

Wilkie’s dad Harry, an Aberdonian like Jean, had been persuaded to move to the South Asia island by his brother. “Uncle Harry had ended up there after the Second World War. He said: ‘You should come for the hunting - buffalo, leopards, crocodiles.’ Dad, an engineer, didn’t bring back any trophies for the walls. Our house was a grand place and we had maids but, really, I lived at the swimming club.” The only other famous Colombo old boy mentioned by Wikipedia is the science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke - did Wilkie ever run into him? “Oh yes. He was a neighbour. Fascinating but also quite weird. One can speculate how he ended up living in Sri Lanka but we shared an interest in scuba-diving and I rented my gear from him.”

Secondly, Wilkie had to become accustomed to life as a boarder at Daniel Stewart’s College. “I can’t say I ever came to enjoy it. Outside of school I was shy and timid. Inside, I got on with it because I had to. I toughed it out.” Thirdly, he had to apply himself at training, but first of all properly understand it. “Up and down the pool, up and bloody down all the time. I didn’t see the point. Monotonous and futile. And of course this was Warrender: tiled walls, nylon ropes, 25 swimmers making the water choppy - nothing at all like the Colombo. I’d come from Sri Lanka with the freshness of the ozone and the lovely smell of breaking waves in my nostrils. At Warrender that was replaced by chlorine and rotten feet!”

Wilkie’s talent had been spotted by a lifeguard but he would bunk off training sessions. “I’d sneak away to this cafe, drink Russian tea, play pinball and then nip to the loos to wet my hair before going back to school. This went on for a while until I was rumbled. The school gaited me for two weeks and my coach gave me one last chance. I knuckled down. When I look back, it’s amazing that I did. Then came the beginning of … I wouldn’t say perfection but at 16 I was competing in the Commonwealth Games [Edinburgh, 1970] and winning a medal. That was unheard of.”

Two years after that came his first Olympics, the fateful Games of Munich. “The swimming had finished and we were winding down with a few beers. We got back to the Games Village about 2am when we saw yellow tracksuits, figures coming over the fence. Security wasn’t stringent - fake passes for friends had been easy to obtain. Then the next morning at breakfast the Canadian team said: ‘Have you heard? … ’” The Palestinian terrorist group Black September took Israeli athletes hostage, 11 dying in the massacre.

Wilkie’s tremendous ding-dong with John Hencken began in Munich when the American won gold in the 200m breaststroke with the Scot taking the silver medal. Swimming gurus at US universities admired Wilkie’s glide and courted him, Harvard and Southern California among them, and he ended up choosing Miami.

Until the Commonwealths in Edinburgh, Wilkie freely admits he’d been a “lazy git”. Now he had the opportunity to have his talent hot-housed, finessed and pushed towards the ultimate prize. “I learned how to be a competitive swimmer in Scotland and then American polished me. Would I have won the gold medal if I hadn’t gone to the States? Who knows, although maybe not. But that’s not to disregard Scotland’s part in the story.”

Just imagine, I say, how much more he could have achieved if instead of skiving he’d been driven from the start. He’s not sure about that, suggesting this may have brought about disillusionment and an earlier exit.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSwimming took hold of him at the optimum moment. He didn’t like the training any more than before - “Let’s face it, this is a pretty boring sport” - but suddenly there was a goal, a dream and a rival he was determined to clobber.

Much later, he couldn’t quite let swimming go. There was an attempted comeback targeting the 1988 Olympics in Seoul. “That arose out of me being asked the question by a journalist and I thought it might have been the beer talking. I was 38 but still the second-fastest swimmer in Scotland. I hooked up with my old coach, Dave Haller, out in Hong Kong. In the end I realised I’d been away from competition for too long.” But what about Glasgow’s Commonwealths of 2014 at the grand old age of 60 - didn’t he try then, too? “Yes, but that would have been for Sri Lanka. I was going to fund a swimming scholarship there in return for a place in the team. The idea was quashed. A shame, I wanted to do it for the craic and am sure I would have loved it.”

But Wilkie will always have Montreal. It’s funny, he says, reflecting on his Olympics being dubbed “the troubled Games” - New Zealand’s participation following a rugby tour of South Africa had sparked anti-apartheid protests and a boycott - when he thinks about athletes in Tokyo huddling under a Covid cloud. “I saw footage of a bunch of them the other day behind barbed wire and looking like prisoners, just before they go out to compete in front of no crowds. The Olympics should be about freedom - mine were. The last truly amateur Games, perhaps, where even if you were gifted a box of Smarties some ramrod idiot official would come down hard. Money flooded into sport soon after but we were still Corinthians.”

There wasn’t much craic between Wilkie and Hencken. “We were completely different personalities - our respective universities reflected that. John was at Stanford, a serious place, and he was a scientist developing rockets. Miami was Suntan Uni where boys and girls went to have fun.”

Over four years they competed against each other in around a dozen collegiate swim meets, honours more or less even, and although Wilkie was world champ going into ’76, Hencken still had an Olympic gold over him.

There was a recurring nightmare for Wilkie, always ending with him finishing second and staring up at Hencken. Coach Haller, though, knew Wilkie was ready, having been astounded by the times he’d posted in training for legs-only breaststroke, an exercise repeated in sets of ten. Then, after raisin bread with butter and a glass of milk for breakfast, it was race day.

By then the Warrender chlorine was a distant memory but Wilkie retained the goggles - “I would fiddle with them when we were introduced on the blocks to calm the nerves. Anyone going after a gold medal is going to have doubts, fears and maybe get really scared. You’re always thinking about failure. If the pressure gets too much that’s when the guys who probably should win, don’t.” But externally at least Wilkie looked like he was back under the Sri Lankan palms, hearing the waves crash onto the beach, without a care in the world: “He was the coolest person I’d ever seen,” according to physiotherapist Tony Power.

Wilkie destroyed the field. Down the final length, with Alan Weeks nearing climax and the TV audience back in Scotland roaring him home, he was no longer thinking about Hencken. He wanted the world record and he got it - 2:15:11, three seconds faster than he’d ever swam before.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

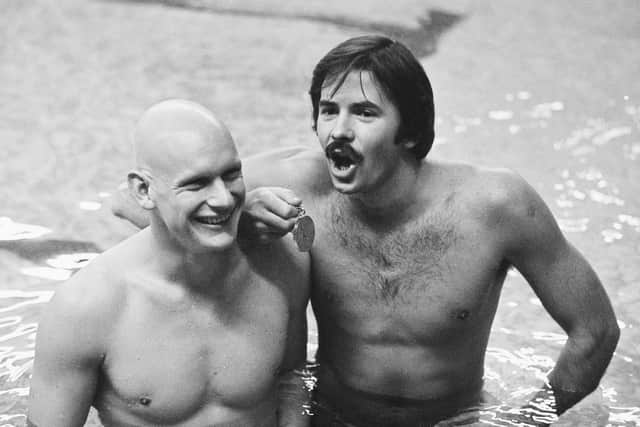

Hide Ad“An unforgettable race,” reported The Scotsman, “overflowing with tension, excitement, emotion and compliments.” In the water, trying to take in his achievement, Wilkie turned to Hencken and said: “It’s been a good four years, John - thanks a lot.”

And on the podium, unlike in the nightmare, he was looking down on the American. “I shook his hand,” says Wilkie, “for what I’m sure was the only time ever. Then we walked away from Montreal and haven’t seen each other since.”

As Weeks so palpitatingly, patriotically put it: “Absolutely superb!”

A message from the Editor:

Get a year of unlimited access to all of The Scotsman's sport coverage without the need for a full subscription. Expert analysis of the biggest games, exclusive interviews, live blogs, transfer news and 70 per cent fewer ads on Scotsman.com - all for less than £1 a week. Subscribe to us today

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.