Ian Stewart chose Scotland over England so he had crowd on side at 1970 Games

The winner of Scotland’s greatest-ever race, which unfolded gloriously 50 years ago this month, lives not far from where he was born, deep in the heart of the English Midlands. But in a thick Brummie accent, Ian Stewart says of his dark blue vest: “You would have had to fight me for it – and even then you would have found it was welded to my chest.”

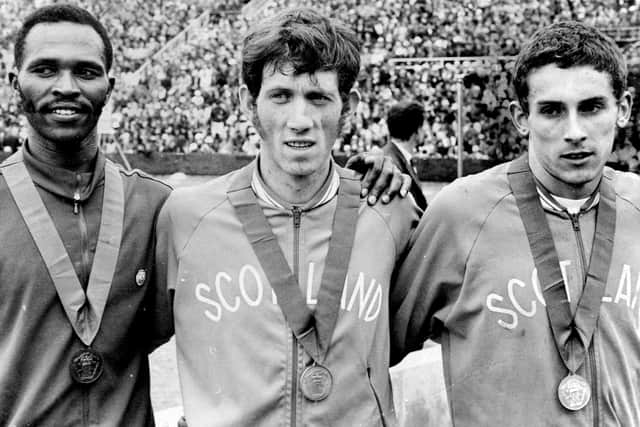

In the 5,000 metres on the last day of the 1970 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh, Stewart and Ian McCafferty obliterated a field of legends. David Coleman’s commentary still sends shivers. “And it’s one-two all the way for Scotland!” he exclaimed as the pair rounded the final bend to embark on their almighty tussle for the gold medal.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHalf a century ago was a golden time for televised sport, inspiring a short-trousered generation. Pele, Tony Jacklin and a spellbinding rugby match – Scotland 18, Wales 19 – sent us scurrying outside to mimic trademark moves. But maybe the most exciting twelve and a half seconds or so was that double dash to the line on Meadowbank’s tartan track.

I am still gripped by the race. As a schoolboy it was possible, knowing nothing about either man, to imagine McCafferty to be the more rock ’n’ roll of the two as Stewart possessed a sensible haircut and the former had sideburns – and because he was trying so hard to catch Stewart, to root for him.

Similar to the contrast which followed between Sebastian Coe and Steve Ovett, was Stewart the personable one and McCafferty the difficult one? This seemed firmed up in my mind in 2014 when I tracked down McCafferty in the wilds of North Lanarkshire where he did nothing to disprove the impression of a rebel, having burned all his team blazers and cast aside medals. At that precise moment, McCafferty was the outsider and Stewart was establishment, the latter having risen to senior posts within athletics. But, as I discover today, they were far more alike than appearances suggested. Just a pity there could only be one winner.

At least Stewart, now 71, has kept his gold. It’s in a box under his bed in the tiny Worcestershire village of Upper Bentley. These days comprising just 37 houses, this appears a very English place, and yet the 19th century “Squire of Bentley” married a Scot to become Maude Mary Cheape and a benign Victorian landowner on Mull, much admired by islanders for keeping afloat a vital steamer. Stewart, alas, didn’t always garner the same respect, with some questioning his right to run for the home nation in ’70.

Part of a fine running dynasty, he explains: “A few years after the Games I was at function when I was cornered by this Scottish athletics official who told me that Anglos had no place in the team. My elder brother Peter was okay because he was born in Musselburgh but I very definitely wasn’t. That shocked me, and our sister Mary even more so. She decided there and then not to run for Scotland like us and when she won her Commonwealth gold in 1978 it was as an Englishwoman.”

These days we hardly notice when participants in Scottish sporting endeavour reflect after the event in tones which are more Kiwi than kailyard, less home rule and more Aussie rules. Compared with the credentials of others reliant on the granny factor, though, Stewart’s are solid enough.

“My father John was a proud Scot who, when Scotland were playing rugby and if he could have got away with it, would have climbed on to the damn roof of the house and waved a Saltire. I was instructed to cheer for Scotland, no question. Dad was on the torpedo boats during the war, based out of Devon which was where he met my mother who was in Bomber Squadron, then he took her up to Musselburgh, his home town, which was where they started the family. Mum had suffered rheumatic fever for 18 months as a girl and after coming out of hospital was told she’d have to live in a single-storey house and would never be able to have children. In the end she produced six of them.” Stewart was born in Birmingham and in a storied career, in addition to Edinburgh, would strike gold in 1969’s European Championships, indoors and out, claim another Euro title on the boards in 1975 and the same year was also cross-country champ of the world. But he was a slow starter.

“Peter ran for England Schools but I wasn’t interested,” he says. “I copied him to the extent of joining a running club, but a small one which hardly ever met while he was at Birchfield Harriers, a famous outfit. Then one day Mum said if I was going to get any better I’d have to move to Birchfield. There was no bloody way I was going to do that. Pete and I didn’t get on as kids as we were completely different from each other. I was a loner.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy then their father was working as a painter-and-decorator but with so many mouths to feed Stewart had to leave school at 15 and go to work at a Birmingham weapons manufacturer, testing guns for both military and recreational use. He eventually joined Birchfield but only intended to run cross-country. “I was hopeless on the track, too slow.” He got better, though, which must have been dispiriting for big brother. “I don’t know if it was or not. Peter and I never had that discussion.” But a key moment when they did converse was about Edinburgh and which colour vest they should wear.

“This was late ’69. My coach, Geoff Warr, and our father were present. I could have made the England team, having ran for them as a junior, but I just said: ‘Look, the Games are in Scotland, if you’re wearing a blue vest with one lap left and you’re right in the race, the crowd could carry you home.’ Peter wasn’t sure but I was. Scots at a sporting event are always more demonstrative than the English. ‘That could gain me two metres,’ I said, ‘the difference between winning and losing.’

I say this sounds like a coldly calculated decision. “That’s exactly what it was. Peter decided he’d run for Scotland too [narrowly missing out on a medal in the Edinburgh 1,500, he would take gold at 3,000 the following year at the European indoors]. Dad didn’t speak throughout the meeting but of course he was a factor in the decision, the emotional element if you like. ‘I’m over the moon,’ he said, which thrilled me. He was a quiet man, travelling by bus to my meets because he didn’t have a car, no one knowing who he was, then afterwards: ‘Good run today, son.’

In ’70 Stewart was one half of a golden couple, his girlfriend being Rosemary Stirling who also ran for Scotland by dint of a father born here and won the women’s 800m. But these were the Friendly Games, a homely affair begun with a modest parade of athletes in flannels and pleated skirts, so you wouldn’t call them the Posh & Becks of their era, and a good thing, too. Later Stewart married US hurdler Stephanie Hightower, though they divorced a few years ago.

The field for Edinburgh’s 5,000m was exceptional. As Coleman puts it: “Five of the first six from the last Commonwealth Games in Kingston and four of the fastest eight of all time in the world over the distance.” Among them Australia’s Ron Clarke, who would set 17 world records in all but never win gold, and Kip Keino – Coleman: “The majestic Kenyan” – who lurked ominously as the two Scots made their move with two laps remaining.

So what of McCafferty: did Stewart rate/fear him? Did he like him? “McCaff was a class act. If he was in the mood you were in trouble. Before Edinburgh, he beat me down here at the big Birmingham meet at Salford Park. He beat me at Grangemouth and also in a mile race at Reading the year before, a great occasion on cinders, 10,000 watching and this Canadian showman at the mic with scripted lines like ‘The devil takes the hindmost’. McCaff came up to me beforehand and said: ‘This is a night for going under four minutes – fancy it?’ In the end me and him and Peter all did.”

Stewart likens McCafferty to a firework, either dazzling or a damp squib. The fellow from the gun factory seemed to be a surer shot and a controlled explosion. “McCaff was erratic. Brilliant one race, nowhere the next. When I won the European title in Athens the year before Edinburgh he didn’t even make the team. Post-Edinburgh, a cross-country in Cambridge, I finished third and he was 90-something. One thing which I reckon counted against him was being a homebird and not racing enough outside Britain. I think he was too scared of his wife to ever venture too far.”

Stewart offers an example of his own attention to detail: “Ron Clarke ran in Stockholm every year. I decided to go there before Edinburgh for the specific reason to beat him and plant me in his mind come the Commonwealths.” Then, although it’s not a direct comparison, he mentions some typical McCafferty mayhem: “McCaff was a plumber, working at a school one day, when he challenged the rest of his crew that he could beat the works lorry in a race the length of the playground during the lunch-break. McCaff was in his overalls, and apparently outpacing the truck, when the driver slammed his foot down only to realise he was suddenly headed straight for the cafeteria!”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith his focus and method it’s no surprise that Stewart would later move into coaching. He worked with Mo Farah before the Olympian was mentored by Alberto Salazar but is reluctant to discuss his former charge, still mired in the controversy surrounding Salazar’s doping ban. Back to McCafferty, though: Stewart was very fond of the harum-scarum contender.

He laughs when I recall being challenged by the silver medallist: “You can try and find me but I bet you’ll get lost.” But he’s dismayed when I tell him about McCafferty having destroyed 20 scrapbooks and almost all evidence of his running career.

“I liked McCaff’s company; many’s the time he had me in stitches with his daft stories. But I think for him I was the exception. I remember a road-run in Edinburgh with Lachie Stewart and all the Scottish middle-distance boys when the needle between them and him was very obvious. I think I was one of the very few people he could tolerate. Similarly, he was one of the very few I could tolerate!” The devil takes the hindmost indeed.

Stewart lists some contemporaries and his intolerance of them including England’s Dick Taylor (“I didn’t get on with him”) and America’s Steve Prefontaine, once described by Coleman as “almost an athletics Beatle” who bumped Stewart in the 1972 Munich Olympics, the latter forced to settle for bronze: “I let the incident distract me too much, which was my fault, resulting in the most disastrous race of my career – but the acclaim for Pre was way over the top because he never won anything.” Brendan Foster is a pal with whom Stewart last year walked the 500-mile El Camino de Santiago, the pilgrims’ route through France and Spain: “He rates Edinburgh the greatest 5,000 of all time.” Another Englishman, and another pal, is David Bedford, who liked to hit the front but had no finish, although his biggest problem was nerves: “He was Harry Have-a-chat, always seeking out company, which didn’t do him any good.” But then not everyone could be calmly Zen like Stewart.

He had a long time to kill in the Games Village before his event but this was no problem. “I’d get asked ‘Aren’t you bored?’ but that question became boring. I brought lots of books with me to Edinburgh, lay on my bed and read them and didn’t get caught up in the endless chatter. The only issues were with my coach and my brother. They were worried about Keino and I didn’t need to hear about him so I took action. I broke off all contact with the coach for five days before the race. I’d been sharing a room with Peter and threatened to chuck him out if he didn’t stop being so negative.”

His preparation produced a perfect run and as he predicted, the Meadowbank crowd were wonderfully raucous, although McCafferty’s charge was a factor in that. “I wasn’t aware he’d got the silver medal, thought it was Keino who’d chased me. I didn’t know until I asked McCaff where he’d finished; he wasn’t too pleased at me for that.”

Last glimpsed on the start-line in Munich, Stewart didn’t encounter McCafferty for the next 42 years. Then, at a Scotland-Germany-Russia meet at Glasgow’s Kelvin Hall, announcer John Ridgeon surprised Stewart by summoning his old foe from behind a door. “We were interviewed for the big screen. John invited McCaff to reminisce about our race and he said: ‘I cannae remember anything’. John tried again, asking about rivalries. McCaff said: ‘You cannae be friends off the track when you’re enemies on it.’

“He was right of course, and although our conversation off-camera didn’t extend much beyond that we met up again a few months later back at Meadowbank and he was much chattier and friendlier. Typical McCaff, showing his two sides again.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStewart was pleased to be back at the scene of his triumph, since demolished. “I had a nice memory of coming out of the stadium in ’70 and bumping into my great aunt Meg from Musselburgh who was thrilled to have been at the race. Dad wasn’t there. He couldn’t afford to make the trip but watched on TV in Birmingham in a pub full of Scottish labourers and I think they enjoyed a lock-in.

“That night I went out for dinner in Edinburgh with my girlfriend Rose, my coach and a sportswriter from home. I wasn’t drinking and neither was Rose, but thankfully the other two were, as a whole lot of booze was sent over to our table. I think some of the other diners were slightly disappointed when they heard this accent of mine, but hopefully they thought I ran a good race.

“Anyway, I did it for my dad. And if you ever see McCaff again, say hello from me, one loner to another … ”

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

The dramatic events of 2020 are having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive. We are now more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription to support our journalism.

Subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app. Visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Joy Yates

Editorial Director

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.