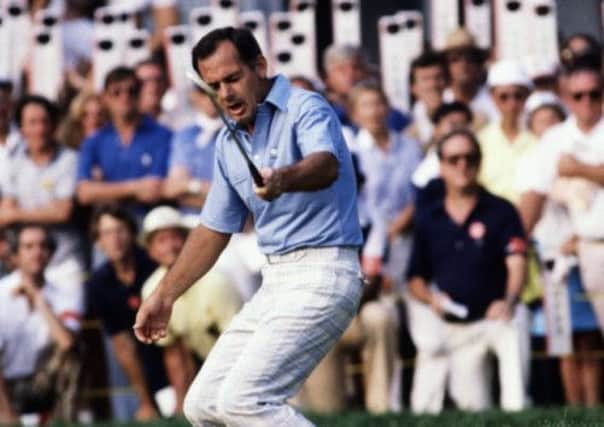

David Graham on his great round at 1981 US Open

EVEN in such a highly competitive field, David Graham’s feat stands out. On the course where, in 1930, Bobby Jones won the US Amateur to complete an unprecedented and never-to-be matched Grand Slam. Where, two decades later, Ben Hogan simultaneously struck one of golf’s most iconic poses and a 1-iron for the ages to the 72nd green. And where Lee Trevino and Jack Nicklaus went head-to-head over 18 holes for the 1971 US Open. Against all that, Graham’s closing 67 at Merion in the 1981 version of what America calls the “national championship” resonates still.

It has been called the “perfect” round. It wasn’t of course, but it was close. The Australian missed only one fairway from the tee – the first, by less than a foot – and hit every green in regulation figures, albeit twice his ball trickled on to the fringe by a matter of inches. So Graham putted for birdie on every hole, making four and three-putting once, at the fifth.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was a performance laced with the precision that was the hallmark of Graham’s highly successful career. Always immaculately turned out, the now 67-year-old was a renowned ball-striker (albeit chronically slow) and one of the most fastidious players of all time when it came to his equipment.

“David is the only guy I’ve seen who re-gripped his clubs every day before he practised,” says Trevino, a close friend of Graham’s. “He’d come out with a pair of scissors and a roll of tape and lighter fluid. He’d put the new grips on, let them dry for five minutes then he’d hit balls. He had all the grass on the practice range dead from the lighter fluid. He was a perfectionist in the way he dressed, spoke, carried himself and tried to play.”

In contrast with today’s “bomb and gouge” generation, Graham built his success – 35 wins around the world, including two major championships – on accuracy. His philosophy upon arrival at the then 6,544-yard Merion layout was therefore not difficult to figure out: “Hit fairways and greens and see what happens.”

“I liked the course right from the start,” he said last week from his home in Montana. “I just had a feel for it. It’s not a long-ball hitters’ course, it’s an iron-players’ course. It’s also a course where it is best to play cautiously rather than aggressively, which suited me. My one big break came on Saturday. I hit my drive off the 14th tee into a bush. But I got away with a bogey. And I stayed with my gameplan. I was determined I wasn’t going to lose by making poor decisions.”

It was the perfect marriage. Graham didn’t make many bad choices or swings and he didn’t lose either. Indeed, 32 years on from what he calls “the biggest victory of my career”, he remains the only Australian ever to win two of the four major championships. By itself, such a distinction should see his name in the World Golf Hall of Fame. That it does not is one of that much-maligned institution’s greater shames.

“I am hurt that I’m not in the Hall of Fame,” he says with some justification. “And I don’t take any pleasure out of seeing people elected that have not as good a world record as I have. I will forever not understand that.”

Quite apart from his stellar playing record, Graham’s life, in fact, is one Hollywood could do worse than take a look at. His has been a difficult journey. When, for example, the 15-year-old David announced his wish to become a professional golfer, his father told him: “Do that and I will never talk to you again.” It was a promise the elder Graham almost kept. Only once thereafter did the pair converse, during the 1970 US Open. But it did not go well and was never repeated.

That lack of success was replicated in Graham’s early life. A natural left-hander, he learned how to play right-handed, an arduous process. Bankruptcy slowed him further in the late 1960s but, by the early 1970s, he had developed a game good enough to earn a PGA Tour card. He won eight times on the world’s biggest circuit, most notably the Memorial Tournament, as well as on six continents. His bigger victories included the 1979 US PGA Championship at Oakland Hills – where he defeated Ben Crenshaw in a play-off – the World Cup (with Bruce Devlin), the World Match Play at Wentworth and the Australian Open, beating a strong field that included Crenshaw and Nicklaus.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEight victories on the Senior (now Champions) Tour would follow his 50th birthday. But even “golf’s mulligan” ended sadly and abruptly for Graham. On 27 June, 2004, he collapsed on the eighth hole of the Bank of America Championship. The problem was his heart. It was pumping at only 12 per cent of its normal volume. And he would never play competitive golf again, even if the game had one more knee in the groin to administer. After captaining the 1994 International Presidents Cup side, Graham was summarily removed from the ’96 matches at the instigation of certain members of his side. Not one of golf’s prouder moments.

It was on 21 June, 1981 that David Graham, golfer, peaked, however. Starting three strokes behind the 54-hole leader, George Burns (no, not the comedian), the then 35-year-old woke knowing ultimate victory was far from guaranteed. But he was reasonably confident.

“I don’t think anyone can ever know beforehand that things are going to go as well as they did for me that day,” he says. “It’s hard to be that presumptuous and think you are going to win. I certainly didn’t do that. And I don’t believe many would, certainly not anyone with any intelligence.

“I knew I was playing well though. There were plenty of indications, not least the fact that I was in the last group on the last day of a major championship. Those facts alone tell you about the quality of your game. I wasn’t off at 8am, so I had it figured out how well I was striking the ball.

“A lot of players play really good golf. And they also play rounds that are pretty close to perfect. They hit nearly every fairway and nearly every green and so score very well. But those rounds tend to be under the radar somewhat. They’re shot on Thursdays or Fridays or even early on Sundays. If you don’t win, even the great rounds don’t get much recognition, short-term or long-term.

“My round was different though. I did it on a Sunday afternoon, on the last day of a major championship and on national television. So it got a lot of attention and recognition. Add in the history of Merion and it is even more special. Throw all that into the pot and you have something memorable. My timing couldn’t have been better. I certainly couldn’t have written a better script.”

Having wiped out Burns’ edge within four holes, it wasn’t until the 14th that Graham took the lead for the first time. Another birdie followed at the 15th and, in the end, he won by three shots. His winning score of 273 was the first time a Merion champion had managed to shoot under the strict par of 280.

“I have nothing but wonderful memories,” says Graham, who rather dispelled his severe image by providing 25 cases of champagne for the press in the wake of his victory.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“And over the last few months I’ve had many opportunities to talk to people about the tournament and the course and everything else. It has been so nice for me to look back. But not many days go by without someone asking me about the final round of the ’81 Open.”

One last thing. What does Graham, a member of the “Cup and Tee Marker Placement Committee” – no kidding – at the Masters, think the winning score is likely to be this coming week when the US Open returns to the cramped confines of Merion – a fact only exacerbated now that the storied venue is 500 yards or so longer than 32 years ago?

“The course will be fine in terms of standing up to the modern player as long as it doesn’t rain,” he says. “If it plays hard and fast, Merion will do just fine. But, if it rains and it gets soft, they will eat it up. A combination of soft greens and lots of wedge shots will inevitably lead to low scores. They do that every week, to be honest, no matter where they play. These guys can do that in the most difficult conditions. They are the best of the best. So someone will light it up.”

Maybe so. But it’s a safe bet that even the new champion will not repeat Graham’s final round statistics. It was, in the circumstances, surely one of the ten greatest rounds of the 20th century. And just one more reason he should be in the Hall of Fame.