Glasgow 2014 won’t match boycotted Edinburgh 1986

It began on the second floor of Edinburgh’s Caledonian Hotel, continued into the lobby and ended amid the West End bustle. Five-star carpets, marble and tarmac – a multi-surface event, then, and one which I had no chance of winning.

No chance because Peter Heatly, the Leith-born former champion diver, was the sole sportsman in the field. No chance because, when your correspondent spotted him, he leaped into the lift, so determined was he, in his role as chairman of the Commonwealth Games Federation, to avoid discussing Zola Budd. No chance because, on the dash down the stairs, I was impeded by a New Zealand TV crew and by the time we’d co-ordinated our pursuit, the spry, diminutive Heatly was already sprinting towards his official car which would whoosh him far from tricky questions about South African-born athletes and the effect their participation could have on the already boycotted and broke Games of 1986.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBack in the Caley Hotel, where a 50-strong hack-pack had waited five hours for a decision only to be given the slip, I was interviewed about what Heatly had said in response to my yelled questions, which was pretty much nothing. Determined not to be caught out again, the reporters prowled the corridors in search of more blazers. There was a comical moment when the pack conga-ed down a staircase in the wake of an English official who had wanted Budd in their team, then back up again when he seemed to forget something. The journos caught sight of themselves in a huge gilt-framed mirror and burst out laughing, and an afternoon of frustration and farce ended with the man from the Press Association – respect, Joe Quinn – grabbing a likely suspect and demanding to know the federation’s decision, only to be told: “Get off – I work for the hotel!”

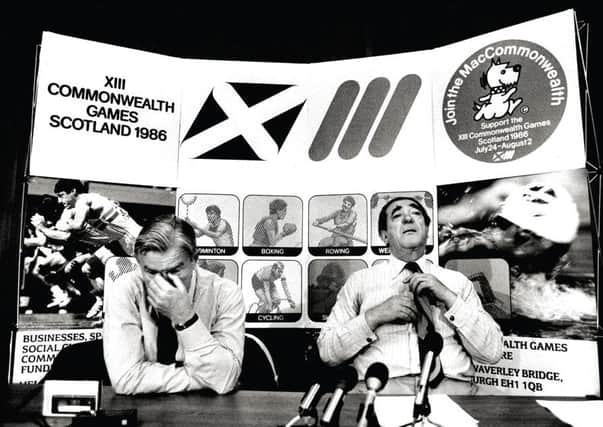

Looking back on those Games – with their key roles for a former lord provost and sweetie-shop man Robert “The Bouncing Czech” Maxwell, a war criminal supposed to have rid the world of leprosy and Margaret Thatcher – it would be easy for that mirror to skew perceptions. We reporters covering the build-up thought the funding calamity, the domino-tumble of black nations refusing to come to Edinburgh and Cap’n Bob’s out-of-control ego amounted to a terrific story, and it did.

But once the Games began – and despite everything, with more than half the Commonwealth nations staying away, they did happen – little of this mattered to the Scottish sporting public. They saw some thrills; they got to acclaim a new local hero in Liz Lynch, later McColgan, pictured left. “Sport wins at the end of the day,” was the headline on Brian Meek’s final report for The Scotsman, and not even the incessant rain mattered. “Stop writing that we are bored,” Meek was told by one woman in a high-performance plastic mac during one of the lengthy stoppages at Meadowbank Stadium. “We are having a wonderful time.”

Aneurin Evans had a wonderful time, too. The Welsh boxer wasn’t a member of the Principality’s original team but was pressed into service when his sport was the worst-hit by the decision of Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana and the rest to stay at home. Now 50 and originally from Treharris in South Wales, he drew a bye straight to the final of the super-heavyweight, was pounded by Lennox Lewis, then of Canada, and took home a silver medal for what the Guardian’s Frank Keating called “four minutes of understandable backpedalling”.

Super-heavyweight is held up as one of Edinburgh 86’s most risible contests and in Brian’s Oliver’s new book on the history of the Commonwealth Games, Evans is described as having “returned to obscurity” afterwards. I think his story might be worth hearing so I take a chance on an address in the English Midlands to write him a letter. It’s the obscure Aneurin Evans right enough.

“I had a fantastic time in Edinburgh,” he tells me. “My first day in the Games Village I got offered a massage. I wasn’t sure; it sounded a bit dirty. But this was a sports massage – lovely. I had quite a few of them because I had to wait 11 days for my fight. I’d never been to Edinburgh before – overwhelming. In fact I was down on Princes Street when the official team photo was happening so I’m blanked out of it. I was playing the slot machines.

“I must admit I came up hoping to meet some pretty girls. By far the prettiest was Princess Diana who visited the Village and I’ve got a photograph of her. Mind you, I’ve also got a photo of Jimmy Savile who came to see us, too. Because of being a late call-up I wasn’t in tip-top condition and maybe I could have trained harder.” In his BBC commentary, Harry Carpenter said of Evans: “He really is out of his depth here. If I were him I’d be running for my life.” Evans discovered this later and says he had no intention of running, or doing anything else not in the Queensberry Rules. “On my way to the ring a couple of guys in the crowd asked when I was going to take a dive so they could bet on the round. Excuse my language but I told them to ‘f*** off’.”

But let’s return to the problems encountered by the Edinburgh organisers, without equal, then or since. Other events suffered boycotting, including the previous two Olympics, but LA in ’84 had Peter Ueberroth, a major-league hustler who created the Hamburger Games, and the first to be privately funded, producing a £250 million profit. Edinburgh had Kenneth Borthwick, a wholesale confectioner who’d been lord provost when the city was routinely under Conservative rule.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Poor Ken – he really was out of his depth,” says Alex Wood, Labour leader when the party finally seized overall control of the capital in ’84. Wood was ferociously anti-Edinburgh establishment so it’s ironic we meet in Morningside. “Yes, this is more Ken’s kind of place. He would have fitted into The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie very nicely. He was a Conservative with a small c and very keen I believe on getting a knighthood. Lots on the council were. The city chambers had the atmosphere of a gentleman’s club before we turned up: small-minded and uniquely snobbish.”

Wood, if you hadn’t already guessed, is not a son of Edinburgh. “Originally Brechin although my dad was a Glaswegian, so there is a connection with one fine city.” He doesn’t appear to have mellowed much. When he describes one old foe as a “right bastard” and another as “an empty fart of a man”, I feel like I’m back on the Edinburgh Evening News covering the ya-boo-sucks of local politicking. But then he says: “Although we disagreed violently, I do have some sympathy for Ken. We were all out of our depth.”

Scan the cuttings from the build-up to what Brian Oliver called “the most bizarre, most troubled Commonwealth Games ever staged” and you’ll find some in the capital wishing they had gone to Glasgow, reckoning the latter would have made a better job of them. Throughout the ’80s the inter-city rivalry was intense and Edinburgh noses were put out of joint when Glasgow went stoneclean-crazy and declared itself “Miles Better”, got itself an arts festival and became European City of Culture. The Evening News despatched me to write “knocking pieces” about the upstarts in the west but the capital was the only bidder for the Games. As Oliver says: “At a time of worldwide recession and great political differences, no one else wanted them.”

Edinburgh had hosted the Games before, of course – the 1970 “Friendly Games”. But the nature of big sports events had changed dramatically in the interim through terrorist outrage, political protest and the coming professional era. Did Edinburgh in its naivety, and with £17m running costs to find, pin too many hopes on a ’70 repeat? “Perhaps,” says Wood, “but what was planned for ’86 was very much in keeping with Edinburgh’s municipal tradition: staid and unadventurous.” TV rights were undersold and the sponsorship drive was too localised. When Maxwell rode to the rescue he called the preparations “appallingly amateurish”.

Within Labour ranks some wished Edinburgh had never been awarded the Games. They had different priorities – leaking windows and other council-house repairs. Wood says he’s always been sceptical about the Games ideal. “They don’t seem to know what they are. A celebration of top-class sport or a couthie collection of English-speaking nations playing bowls against each other? I’ve nothing against bowls but… ” He insists, though, he didn’t want to see them fail and quickly joined the organising committee so presumably he isn’t entirely blameless for the mistakes made. Many others moved across from the council. On a visit to Games HQ, the Duke of Edinburgh surveyed a list of 384 names and spluttered: “You could get rid of that lot for a start!” With the opening ceremony just two weeks away, the Games were still £4m short.

Of Maxwell’s intervention, Wood says: “There were no other offers. I’ve never met anyone like him before or since – he was quite unique. A man whose past lent him a Great Gatsbyesque aspect: Jewish-Czech war hero, spoke ten languages, Labour MP, press baron, owned football clubs. He had a lot of what seemed to be shreds of credibility. Add them together and you might conclude: ‘This must be a good guy!’” So what was he really like? “A man with enormous power who oozed bonhomie. An example of that power was the Games meeting at his office in London which overran and the Edinburgh guys were worried about missing their plane. ‘Stay,’ he commanded. ‘I have my helicopter on the roof’.” So was that power seductive? “Well, he had a monstrous ego as well. And then there was the complete ruthlessness of the man. When he wanted something done he just told you to do it, although not in a nasty way – he was just so confident of his own potency.”

Maxwellian pronouncements included “Jerusalem wasn’t built in a day” and “This is like the Battle of Arnhem. Of course we lost at Arnhem… ”

But not even he could prevent the boycott. While other sports shunned apartheid South Africa, British rugby players continued to fraternise. The black African nations were angry with Thatcher, even more so when she refused to hit South Africa with trade sanctions. Wood was aware of the depth of feeling, having got himself arrested in his Militant days for attempting to halt a Springboks tour match in Hawick – “You waited for a lineout to happen close by, then you ran on” – and again at the city chambers the night the SA ambassador was being wined and dined. Wood thinks Borthwick could have issued a statement distancing the Games from Thatcher’s position. “That would have definitely put the kibosh on his knighthood, and maybe the boycott was always going to happen anyway.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThirty-two teams and nearly 1,500 athletes stayed away, but the self-styled saviour of the Games ensured the show went on. With a box of coins at the ready, Maxwell could tell the Queen: “Permit me to present you with a token of this great event that I have organised.” He secured great publicity for himself and his papers without having to pay very much. Marketing consultants calculated the exposure as being worth £4.3m; Maxwell didn’t even pay £0.03m for it. Journalists – those from non-Maxwell titles – were incensed by his hijacking of the Games but even the most morally righteous of them would have to admit they loved telling the story of the man’s lack of coyness in other areas: the commandeering of cars and hotel suites already allocated to Games officials; the receptions where he served Kentucky Fried Chicken or roared at Chinese restaurants which didn’t do takeaways: “Just tell the manager it’s for Robert Maxwell of the Commonwealth Games!”; the unveiling of his special friend Ryoichi Sasakawa who may not have eradicated leprosy as stated but contributed more than four times as much as Maxwell to the Games’ cause. The Japanese philanthropist told his stunned Edinburgh audience he’d live until the age of 200. In the end he only made it to 96. An obituary described him as “the last of Japan’s A-class war criminals… a monster of egotism, greed and ruthless ambition and political deviousness… almost a lovable rascal”.

Oliver says that despite ’86 featuring Daley Thompson, Steve Cram, Steve Ovett, Linford Christie, Ben Johnson, Sally Gunnell, Lynch, Lewis and sundry others, Cap’n Bob was the most written-about figure. That’s probably true, although if you were a firmly-focused sportsman you saw it differently. Scottish cycling bronze medalist Eddie Alexander is another from ’86 who is difficult to track down. Working as an executive in the oil industry, he is often in Azerbaijan. “I knew there were some problems with money,” he tells me. “Who was it came in again… [long pause] Maxwell?”

A product of the Clachnacuddin Cycling Club, Alexander faced long rain delays. Yes, they cycled bareback in those days, or rather bare-topped. The velodrome built for the Friendly Games was supposed to get a roof 16 years later but it never materialised. He just laughs, though, when I suggest that cyclists in the sport’s current sexy incarnation are big jessies for riding indoors.

“That was the way it was back then,” says Alexander, now 49. “Of course it’s great there’s Lottery money and legacy now but in our day the local councils had to take on the sports burden. I first cycled the velodrome in 1979 en route to a schoolboys race in Holland. Despite all the creaks and groans from the wood having warped and lifted, I thought it was fantastic. The track was replaced for ’86 but obviously we couldn’t do anything about the rain.”

The showers were frequent and heavy. The competition overran so much Alexander missed his appointment with the Queen at her garden party. The hold-ups – which sometimes required volunteers to attack the sodden surface with hot-air blowers and then for officials to declare it “dry enough” – disrupted his sprint semi-final with Canada’s Alex Ongaro. “We couldn’t finish and had to come back the next day. I tried to stay focused but I ended up getting no sleep and not riding very well.” Alexander, though, won’t hear a bad word said about ’86. “Sport back then was still more or less amateur. Yes the Games were done on a shoestring but I don’t think of them as being anything other than a success.”

So what was the legacy? It’s there if you look. Alexander inspired Chris Hoy. ET on a BMX was the future Olympian’s first hero on two wheels but then he saw Alexander dodging those puddles.

And remember Aneurin Evans, pictured below? He decided against turning professional after the Games. “Folk used to say: ‘You were such a gifted fighter but you were lazy.’ It’s true that I was far more interested in what came with the boxing: all that attention from women.” But he defended the honour of ’86. “I used to get guys coming up to me in the pub fancying their chances with me. They thought I’d got a medal for just turning up. But the boycott wasn’t my fault. I didn’t like that aggro but let’s say these fellas weren’t very successful.”

Then there’s the legacy of the Commonwealth Games themselves. If the sweetie-shop man and his cronies hadn’t stepped in, the sequence might have been broken.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNow, at last, Glasgow get their chance. Our friends in the west should be able to provide more competitive sport but will surely struggle to match Edinburgh for off-track drama, chaos and unintentional comedy.