Trailblazer Alex Williams recounts surprise Queen of the South stint, iconic Man City match, Klu Klux Klan taunts and what Arsenal legend said to him

“It was at Palmerston, that’s what it's called, isn’t it? It was strange the way it all happened. Billy McNeill was my manager, he was friends with Mike Jackson, the manager of Queen of the South, I remember the name because obviously Mike Jackson is not a name you forget …”

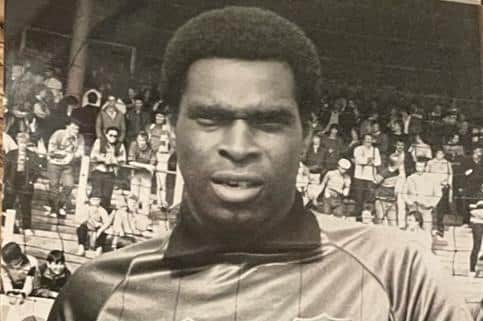

Not in the mid-1980s, certainly. Alex Williams is recounting the journey he made from the English top flight to the old First Division in Scotland. From Manchester City to Queen of the South, from being labelled one sort of bastard to another sort of bastard.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was a noteworthy path even then, particularly since his previous appearance and final-ever game for Manchester City was against Manchester United. His next outing after that 3-0 defeat? It was Queen of the South v East Fife 12 months later, crowd 2,306. Not too shabby an attendance at all, but still some way short of the 48,773 who took in the Manchester derby.

It was September 1986, the same month as The Sun first used the term ‘wacko Jacko’ to describe the other 'Mike' Jackson on its front page. Alex Ferguson was playing out the final weeks of his Aberdeen reign before changing the face of English football at Manchester United. Meanwhile, Williams was consulting his road map before heading for Dumfries and his digs at the Balmoral Hotel, owned by Queen of the South chairman Willie Harkness.

Even the fact he drove himself there is evidence that his back problem – the reason he was seeking to kick-start his career in the second tier of Scottish football – wasn’t being taken seriously enough. It wouldn't happen now. For a start, Queen of the South would be quickly crossed off the list of possible destinations on account of their artificial pitch.

Back then, like all Scottish grounds, it was grass (Stirling Albion installed the first artificial pitch in Scotland the following season). There were more black players than artificial surfaces in Scotland at the time – though only just. Victor Kasule started the campaign at Albion Rovers and ended it with Second Division champions Meadowbank Thistle. Mark Walters signed for Rangers on Hogmanay in 1987.

Williams, whose parents hailed from Jamaica, says he felt welcome in Dumfries, where he deputised for the injured Alan Davidson for five games. “I remember walking into the ground, a young kid walked up to me and said, you are the Man City goalkeeper and he said, you are on X number of pounds a week. It was not a huge amount – but he was actually spot on. It was like, how does he know that?! But the fans made me feel at home as soon as I walked in. The manager asked me what clan I am. I was like, ‘What do you mean?’ 'You know, what clan?' he said. I told him I didn’t know. He said, ‘Well, we will just put you down as the Black Watch’.”

One phrase comes up a lot when interviewing Alex Williams, now 62: They were different times. “Everyone had a little chuckle and I did as well. They were great lads. I don’t remember an awful lot about the games.”

Queens won the first one 2-0, but Williams conceded five times on his next appearance – a 5-2 midweek defeat against Morton at Cappielow. A 1-1 draw against Dunfermline and 3-1 defeat to Dumbarton, both at Palmerston, followed. He rounded off his Scottish sojourn with a 4-3 win at Montrose in front of 544 spectators.

“What I do remember is that, obviously down in England, especially the away games, I had endured a lot of racism,” he says. “Whatever you could call a black person I got called. When I went up to Scotland and ran out to play the first away game I was expecting all sorts of abuse about the colour of my skin. Nothing. Instead, they referred to me as an 'English bastard', which I found amusing.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is unlikely a player will ever go from first-team player at Manchester City to Queen of the South again, even on loan. It was – yes, that phrase again – a different time, although City manager McNeill's friendship with Jackson – they were at Celtic together – was clearly a major factor. Still, the move raised eyebrows.

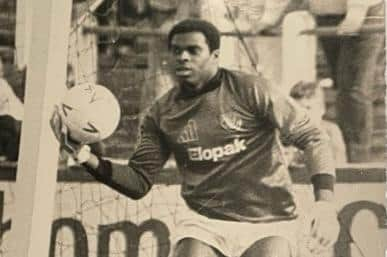

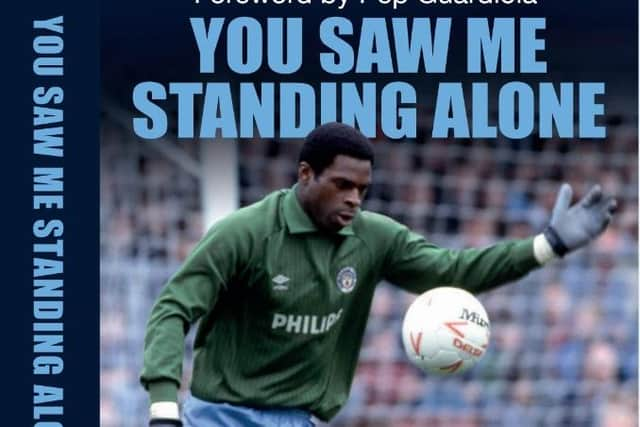

Williams was no normal player. He was the first black goalkeeper to play in the English top flight and suffered for such presumption. As recounted in a book published in September called You Saw Me Standing Alone, a scrunched-up programme set alight to resemble the burning crosses branded by the Klu Klux Klan greeted him as he made his way to his goal at Everton. Razor blades were sent to him in an envelope before a game at Chelsea. It made the sadly commonplace hurling of bananas into his goalmouth appear almost humdrum.

Williams was just 18 when he made his debut for Manchester City. He had to cope with finding his feet at a grand English club, albeit one beset with financial problems, while performing the role of trailblazer. “I never thought of it at the time. But I have since met Ian Wright, whose two sons played at City. I introduced myself to Ian. I said, 'Hello, I am Alex Williams'. He looked at me and said, 'You don’t have to tell me who you are. When the bell went at high school for lunch I used to run down the stairs and go in goals in the playground pretending I was Alex Williams'.”

Wright ultimately excelled further forward. Others remained between the sticks, inspired by Williams. “I have since spoken to Shaka Hislop, David James, who all speak highly of me. I gave them the fortitude to go and play football. Now there's (Andre) Onana at Manchester United, many others."

Although black footballers were creating room for themselves in the mid-1980s, it came at a cost, as Williams discovered. That can still be the case now. He was intrigued to discover that there is now a black manager installed at Queen of the South, one who has bravely articulated the continued struggles. Two years ago, Marvin Bartley wrote that he could go into his Instagram inbox and be guaranteed to find at least two unsolicited messages containing insults about his skin colour. Bartley has since stepped into front-line management with Queens and little that's happened in the interim suggests his experience is radically different now.

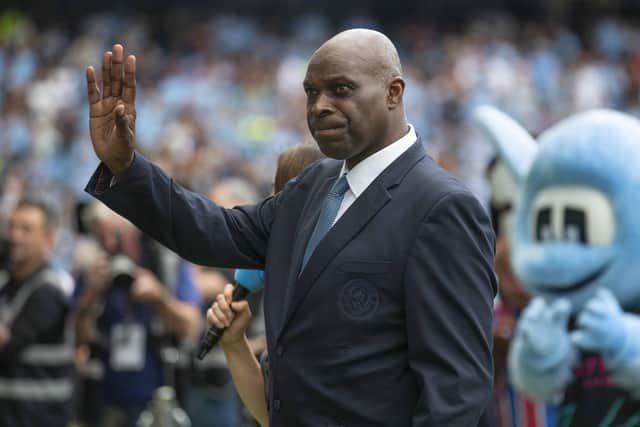

Williams recently met Eilidh Barbour, Bartley’s sports presenting partner, at a North-west (of England) football awards’ night. Barbour was co-hosting the event and he was collecting a lifetime achievement award for 33 years’ service with Manchester City's community charity programme. Williams mentioned his brief stay at Queens and she duly informed him of the current manager's identity. “Maybe I will send him a copy of the book,” Williams says with reference to Bartley.

He's never made it back to Palmerston, where he says he was only 60 per cent fit. The back injury proved chronic and he was forced to quit shortly afterwards, aged just 25. No benefit game, no testimonial. “Manchester City did not really have the money. (Chairman) Peter Swales, a lovely bloke, was not in the wealth league where he could grant a testimonial and raise £30-40,000.”

Some consolation for Williams was knowing he had already achieved so much, including being one of the few goalies to ever save a penalty from West Ham United's Scottish full-back Ray Stewart. "At the end of the game the West Ham players made a guard of honour and clapped me off the pitch," he recalls. There was less acclaim when he saved Pat Nevin's infamous 'worst penalty of all-time' in a 4-1 defeat at Chelsea since it only required him to fall on the ball, although he's slightly miffed he doesn't receive more credit. "I could have gone the other way," he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe has come to appreciate the full extent of his contribution only belatedly. "A raw teenager trying to make a name for himself in arguably the toughest league in the world required nerves of steel," he writes in his memoir. The fact he was black, a goalkeeper and seeking to make the breakthrough "in racist Britain in the 1980s" was, he concludes, "unprecedented".

He is remarkably relaxed about what he endured. In a way, he says, the abuse started washing over him. Not so his father, who he banned from coming to watch him. “I stopped him going to the matches because I am quite flexible around racism, but my father had zero tolerance,” he says. “If I made a mistake and someone said something he’d be up there in the crowd … I had enough trouble on the pitch without having to worry about that."

Millwall away was one assignment where he didn't need any additional stress. "In some ways it was good we got beat, which allowed us to get out of the ground. Had we won I think I would still be there now trying to get out… It was a big learning curve. Other than perhaps playing away at Chelsea, I didn’t really get anything worse than that." The game? A Youth Cup final second leg. Williams was 17-years-old.

*****

It might seem odd to begin the second part of an interview with Alex Williams with a quote from his wife, Julie, but she has joined us in the Manchester hotel where we met last month. It's her story as much as his. They have been together for over 40 years, through thick and thin, through success and failure and across more than just one supposed 'divide'. Not only is Julie white, she’s from a family of Manchester United supporters. When her father heard she was seeing a Manchester City youth player, he badgered her: 'So when are we going to meet this goalie fella, then?!'

She adds: “I never once felt I had to say, oh by the way, he’s black. It was not discussed. On the day Alex met my mum and dad, it was Boxing Day, I remember looking down the path. My dad shouted, ‘Alex is here!' Alex came in, they shook hands and spoke. My dad said: 'I wish you had warned me' – and for a split second I was like, what?! – 'how huge his hands were!' The only thing my mother said, after we got married, was that in the future you might decide to have children, and she said it will pull at your heartstrings. I said, 'What will?' She said, 'I am a mother. You won’t understand now but, because they will be mixed race, some people and children will be cruel. It will be hard.'”

There was no issue on that front because they chose not to have children. The football genes have been inherited by Williams’ nephew, Ethan, who plays midfield for the Under-18s at Manchester United. It has further muddied the waters when it comes to club loyalties within the family. "The strings were always pulled back to City, because of Alex,” says Julie.

Williams never let them or anyone else down. A reverse of the famous Aguero moment 11 years ago, when Manchester City became English champions for the first time since 1968 with a winner deep into injury time, dethroning rivals United in the process, was the final game of the 1982-83 season. City needed a point to stay up. Luton Town, who they play this weekend at Kenilworth Road, were the visitors. Luton required a win to save themselves and simultaneously deposit City in the second tier for the first time in 16 years. It seemed unthinkable that City would suffer this fate. They were ninth as recently as December.

They were fourth bottom with four minutes of the season left. Maine Road was tense and goalless. Brian Stein slung in a cross that Williams managed to punch but only as far as substitute Raddy Antic, who was lurking on the edge of the box. Williams got a touch to his shot – it might have been better if he hadn't, as the deflection took the ball away from a covering defender and into the back of the net. After the final whistle Luton manager David Pleat skipped inelegantly across the pitch in his flapping beige suit and cream-coloured loafers, one of football’s iconic 1980s moments.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNot that Williams will call it that, although he was alert to the significance, and what it could mean for him personally. City were already being linked with a move for Pat Jennings. But while there were huge changes, including McNeill's surprise appointment as manager, Williams kept his place. "The Scottish influx came in," he says. McNeill, already alarmed at finding the purse strings so tight, was forced to turn to contacts and players he already knew, such as Derek Parlane, Jim Melrose, Jim Tolmie and Neil McNab. "They did brilliantly," says Williams. "We were close to coming up the next year. We had a much better season the one after. Those two seasons I think I played every single game. I had a run of about 105 games without missing a game."

They came back up two years later, beating Charlton 5-1 on the final day. "I played all 42 league games and had 21 clean sheets, so every other game was a clean sheet and we only went up on goal difference. If anyone was to point a finger at me about the Luton game, I could say in my own mind, ‘OK, but two years later I played a massive part in us coming up’. Not that I needed to justify the Luton game to anyone but myself."

You Saw Me Standing There by Alex Williams MBE is available for £15 from alexwilliamsbook.co.uk

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.