The Old Firm Story: Graeme Souness revolution at Ibrox

When Jock Wallace led Rangers to a second domestic treble in three years under his guidance in 1978, the Ibrox club looked to have firmly wrested the balance of power in Scottish football back from Celtic after the unprecedented period of dominance masterminded by Jock Stein.

It proved to be an illusory state of affairs for Rangers as the Old Firm duopoly was dramatically shaken up by the emergence of Aberdeen and Dundee United as serious players on both the domestic and European stage. Under the brilliant management of Alex Ferguson and Jim McLean respectively, they were tagged the New Firm as they regularly plundered silverware which the Glasgow giants had almost come to regard as theirs by right.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile Celtic’s response to the challenge now posed by the Dons and United was resilient and effective enough to see them still win four championships in the period from 1979 to 1986, Rangers reeled into a tailspin of underachievement.

John Greig, while unfortunate not to land the domestic treble in his first season at the helm following Wallace’s acrimonious departure to Leicester City in 1978, was unable to replicate as a manager his stellar feats as a player for the club.

When Greig resigned in 1983, Rangers failed in bids to persuade both Ferguson and McLean to transfer their obvious managerial gifts to Govan. Instead, Wallace returned for a second spell in charge but could not arrest the decline in which Rangers supporters became wearily accustomed to fourth or fifth-placed finishes in the championship.

With Rangers lacking direction and purpose on and off the pitch, the seeds of unimaginably radical change at the club were sown in the Nevada desert by a reclusive 42-year-old millionaire in late 1985.

Lawrence Marlborough, grandson and heir of former Rangers chairman and property magnate John Lawrence, struck a deal to increase the Lawrence Group of companies’ share in the club to 52 per cent. For the first time, Rangers were under majority control of one shareholder. Marlborough remained an absentee landlord, nominating David Holmes as his representative and de facto chief executive on the board. If that appointment generated minimal media coverage, Holmes’ first major decision in his new role generated front and back page headlines in Scotland and beyond.

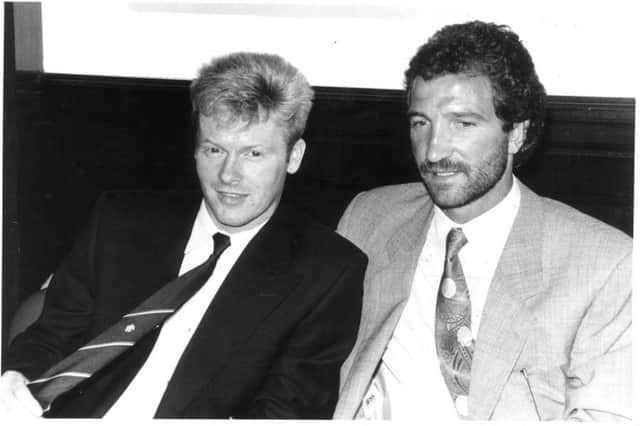

In April 1986, having taken time to assess the extent of the malaise afflicting Rangers, Holmes sacked Wallace and replaced him with Graeme Souness.

Just 32 and still Scotland captain, the former Liverpool midfielder breezed into the job with all the dynamism, self-assurance and ruthlessness which had made him one of the most accomplished and successful players of his generation. With Holmes ripping up a wage structure in which the best-paid players at Ibrox were picking up no more than £300 a week at the time – less than their contemporaries at Celtic and Aberdeen – Souness was able to embark upon a recruitment programme which left the rest of Scottish football gasping in astonishment.

With the ban on English clubs from European football in the wake of the Heysel Stadium disaster the previous year indirectly providing the now big-spending Rangers with additional pulling power, Souness was able to use the force of his personality to persuade a series of high-profile English players to join him at Ibrox. The capture of Terry Butcher, who turned down Manchester United to instead become Souness’s first captain at Rangers, was emblematic of the scale of ambition being displayed by a club which had languished in the doldrums for so long.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe impact was immediate, Souness leading Rangers to their first title in nine years, Butcher scoring the goal which clinched it at Pittodrie in May 1987.

Success and serenity seldom went hand in hand for Souness, who was sent off on his debut against Hibs at Easter Road, one of three red cards he collected as player-manager of Rangers. He was constantly at loggerheads with match officials and the SFA, even incurring a staggering two-year touchline ban as the transgressions totted up.

Celtic’s response to Rangers’ first title win under Souness was the sacking of Davie Hay as manager and re-appointment of the iconic Billy McNeill for a second spell in charge. It paid an instant and unforgettable dividend for Celtic supporters who revelled in a league and Scottish Cup double in their club’s centenary season of 1987-88. But it proved a temporary bump in the road for the Rangers’ juggernaut piloted by Souness and, from November 1988, funded by Edinburgh businessman David Murray who had purchased Marlborough’s controlling interest in the club for £6 million.

The championship was reclaimed in 1989, the year in which Murray and Souness also pulled off the most astonishing transfer coup in Scottish football history when they signed former Celtic striker Maurice Johnston from French club Nantes.

Johnston had been poised to return to Celtic, where he was even paraded by the club at Parkhead before the deal was formally concluded. In snatching him from Celtic’s grasp, Rangers both ended their long-standing and lamentable policy of not signing Roman Catholic players and secured the services of a top-quality international who helped them cement their status as the pre-eminent force in Scottish football.

A few weeks before Rangers clinched a third successive title in 1991, Souness departed as dramatically as he had arrived, unable to resist the lure of returning to Liverpool as manager. After just five years at Ibrox, the Rangers he left behind was almost completely unrecognisable on and off the field from the one he had joined to such seismic effect.

The good times continued to roll domestically for Rangers supporters as, under Souness’s successor and former assistant Walter Smith, the record of nine consecutive title wins set by Celtic under Stein was equalled and elite-level players such as Brian Laudrup and Paul Gascoigne brought their brilliance to Scottish football.

Murray’s financial strategy and ambition for Rangers, of course, would ultimately prove overreaching and lead to the extraordinary events of the past few years at Ibrox which will be addressed in the final part of this series.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut not before the Old Firm traded heavy-weight blows again in the late 1990s and 2000s, the arrival of Dick Advocaat as Rangers manager counter-acted by a financially and strategically revitalised Celtic’s appointment of Martin O’Neill.

Just as Souness had done at Ibrox, so O’Neill was able to drag Celtic out of a torpor which had afflicted them for so long. With the New Firm reduced to the roles of also-rans, Scottish football had a firmly established two-horse race at the top once more.