Stuart Lovell on Hibs cup heartache, Livingston Hampden glory, doing the running for Latapy and Sauzee and his new charity role

Lovell had previously played for Hibs but Livi’s captain simply didn’t fancy them that day, despite the Leith team’s golden generation starting to flower. “I laugh about it and am still baffled as to why so many people reckoned Hibs were such strong favourites.

“My mate told me he didn’t think it was worth us even turning up. I pointed out we weren’t playing the 40,000 fans Hibs would be bringing to Hampden but a side which I didn’t think matched up well to ours. ‘Who’s going to win you the cup?’ I asked.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“‘Derek Riordan,’ he said. “I said he was going to be playing against Dave McNamee who could run 100 metres in 10.9 seconds so Deek wasn’t going to be getting away from him. Meanwhile on the other side of the park we had Jamie McAllister - an absolute flying-machine.

“My mate came back with Garry O’Connor. I said: ‘We’ve got three centre-backs: Marvin Andrews will win all the headers, Oscar Rubio would kick his granny for a fiver and Emmanuel Dorado will pick up the pieces.’

“‘Look at our midfield - Scott Brown and Kevin Thomson,’ he said. ‘But we’ve got three in there,’ I said, ‘Lee Makel, Burton O’Brien and myself. We’ll dominate. And we haven’t even talked about your defence yet - the weakest part of your team. There’s a lack of pace. David Fernandez and Derek Lilley can exploit that.’”

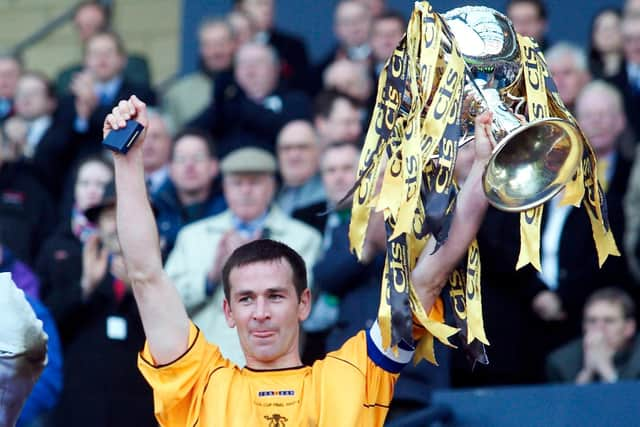

Which is precisely what happened, the Lions winning 2-0 to stun a support almost four times as large as their own and secure the club’s greatest day. Until tomorrow, perhaps, when a guy with an almost identical backstory to Lovell has the chance to lift the trophy again.

The similarities with Marvin Bartley are remarkable. The latter is born in Reading, Berks, and is a youth team lad there while Lovell spends eight years with the Royals. Both become Hibees and share the disappointment of not being picked for a Scottish Cup final. Seemingly surplus to requirements, both move to Livingston and grow in influence as club skipper.

And, I point out, both display a flair for overhead-kick spectacularity that was, shall we say, kept a closely-guarded secret at Easter Road. “You’re right,” laughs Lovell, twice capped by Australia. “Mine came against Rangers in 2002 and was the favourite of all my goals. It was sweet for coming against my old boss at Hibs [Alex McLeish] but more importantly it helped Livingston win the game and clinch third place that season. Afterwards Winker [Andy Watson, McLeish’s No 2] said: ‘What the bloody hell was that? You never did it for us!’”

Lovell, 49, is still apologising for that 2004 Hampden triumph. The HQ of the charity Street Soccer Scotland are in Leith and when he walked in there last October his new colleagues immediately declared themselves as Hibbies and issued low-level abuse.

Helping the socially disadvantaged, Street Soccer Scotland are dedicated to creating what the mission statement calls “purpose and hope” through football. This very good cause, with Sir Alex Ferguson among the ambassadors, is aimed at the homeless and long-term unemployed and those with addiction and mental health issues.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLovell explains: “I wasn’t a superstar, just a journeyman, but football is a very privileged life and now I just want to give something back.” He’s loving the gig, even though Covid has made it extra-challenging. “Lockdown has been hard on everyone but especially those who struggle with isolation and we’ve had to rely on Zoom to keep everyone engaged. Still - and here I’m going to plagiarise my old Livingston team-mate David Bingham, though minus the Dunfermline accent - ‘Better auld soup than nae soup.’”

Lovell has been able to exploit his contacts in the game for some pretty decent Q&As. “Stephen O’Donnell did one the other day and he was great. He’s a salt-of-the earth bloke who’s become a Scotland international. I’m sure some of them went away from the session thinking: ‘That could have been me, maybe.’” Now, though, the ambition is more modest: to simply get back to kicking a ball about together again.

Our man and Bartley may have something else in common: did leaving Hibs improve their status among the club’s fans, a case of not knowing what they had until it was gone? Lovell smiles: “I asked Marvin about that recently. He knew what I meant although maybe it wasn’t as categoric for him as it was for me. Marvin could be hidden away for some games at Hibs but they always brought him out for the Edinburgh derby because he was so combative. Me, I definitely felt more appreciated by the Hibs support after I left.”

Now Lovell is remembering a game at Stair Park in 1998 where the under-appreciation was highly animated for 89 minutes until a dramatic denouement. Hibs were in the second tier and making heavy weather of it. Little Stranraer had already beaten them at Easter Road in what was Lovell’s home debut, and this despite their bus driver being caught unawares by Edinburgh Festival congestion and reaching the ground late.

“My best man at my wedding, Pete McDonald, kept saying: ‘When can I come and see you play?’ I wouldn’t have chosen that match - or any at that time because we weren’t playing well - but he did. He was right in the middle of the Hibs fans, a fantastic away support as it was throughout that season, and this big guy was going through the team-list: ‘Holsgrove - who they f*** is [Paul] Holsgrove? Prenderville - who they f*** is [Barry] Prenderville? And Lovell - who they flamin’ f*** is Lovell?’

“To this day Pete quotes that back at me and he’s become pretty good at the Leith accent. The abuse the bloke dished out was something else. Pete maintains he’s never laughed so much, tears streaming down his face the whole game. Then in the 90th minute I popped up with a diving header to win it for us, whereupon my arch critic turned round to the rest and said: ‘Great result for the Hibees!’ On the journey back Pete said: ‘You’ve joined a madhouse.’ ‘I know,’ I said, ‘but I don’t mind the abuse and the team will get better.’ And we did.”

Lovell was born in Sydney, in the same Parramatta suburb where Aussie Test captain and later commentator Richie Benaud learned to play cricket. But soon his father, London-born Colin and mum Edwina, originally from Kintore, were hurrying him and big brother Simon onto a boat bound for the UK, a six-week haul which may explain his aversion to sailing.

The highpoint of his time at Reading was lining up in a Wembley playoff in 1995, just 90 minutes away from the club joining England’s top flight. The low-point was, with his side two-nil ahead, missing a penalty - Bolton Wanderers going on to win.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Football’s not about fairytales,” he says, “and you don’t get everything you want. If that was the case I would have scored that penalty and played in the English Premiership and I would have been picked for the 2001 Scottish Cup final with Hibs. Stuff like ‘Our name’s on the trophy’ is nonsense. That penalty was on me; no one else missed it. You have to take ownership of those bad moments.

“After that game I did the only thing I could do - hit as much booze as I could to try and forget what had just happened. I woke up the next day with a terrible hangover and wondered: ‘Is there a chance it was all just a bad dream?’ Unfortunately the front page of the newspaper on the mat had a photo of the penalty save.

“Then I thought: ‘I’m going to fix this. I’m going to be the guy who drives us to promotion and the fans will forgive me.’ It was a terrible decision. The team broke up and went on the slide. After finishing up I worked for the players’ union for ten years and always told guys: ‘Make sound judgments for yourself and your career.’ Foolishly I stayed three more years at Reading and no one cried any tears when I left.”

McLeish was at Wembley that day and would make two signings from the personnel on view - Mixu Paatelainen, who scored for Bolton, but first Lovell. “I had a few offers from other clubs in England but Alex was charismatic and I liked his conviction and lack of bullshit. He said: ‘The [old] Scottish First Division is the poorest standard of football you’re being offered but we’ll walk it and get back to the Premier.’”

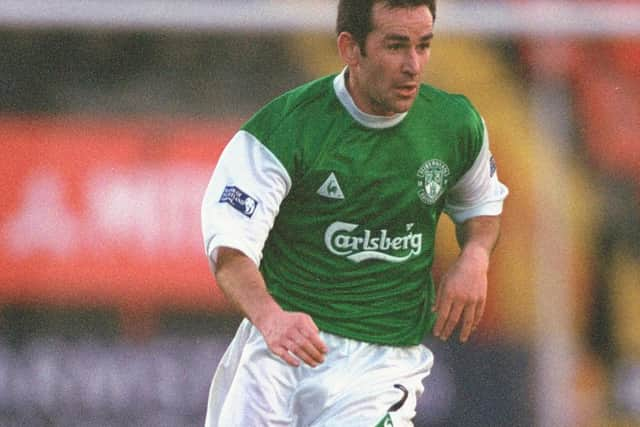

Lovell was three seasons at Easter Road. He thought he did well enough in the first, when having been signed as a striker he failed to click with Stevie Crawford so was moved into midfield, and also in the third when he played as a wing-back. “The problem season for me was the middle one. There was high expectancy among the supporters and I struggled with the system we played.”

Incredible as it seems now, the turn-of-the-century Hibees featured the divine talents of Franck Sauzee and Russell Latapy. McLeish decided these would best flourish in a diamond formation, not Lovell’s favourite way to play, which in that campaign left the team short of legs. “We were outnumbered in the midfield. Franck couldn’t run and Russell wouldn’t run but it would be the other guys - Pat McGinlay or Grant Brebner or myself - who’d get it in the neck from Alex. I had plenty of fall-outs with him.

“I also took a power of stick from the punters. My wife Nicola came to games at that time but she stopped. The flak I was getting scarred her. I told her she didn’t need to be there. I wasn’t one of those guys who was always waving up at their fan club. She wondered how I could stand the abuse. What choice did I have? I said I could hardly wade into the crowd and leather those dishing it out - ‘In case you hadn’t noticed there are always quite a lot of them!’”

Lovell is at pains to stress that while required to fetch and carry for Sauzee and Latapy he understood his place in the grand scheme and loved playing alongside the pair. “Russell arrived first, after a bounce game at Brechin. One of the youths, who’d watched it, said: ‘Wait until you see this wee guy from Trinidad.’ At training I was like: ‘Go on, impress me.’ You can usually tell about a player from the first touch and Russell’s was immaculate.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“His debut was at Ayr United. I had a poor game that day and was annoyed with myself because I’d wanted to impress him: ‘You and me, mate, playing in the same team.’ Every time after that I hoped he might think I was at his level though obviously I knew I wasn’t. But Russell never acted superior, as if Hibs were beneath him, and neither did Franck.

“His debut was at Falkirk. Apologies to their fans but this was Brockville, an absolute dump with cold dressing-rooms and condensation running down the walls. I was sitting next to him and thinking: ‘What the hell is he doing here?’ The pitch was a quagmire but Franck was like a ballet dancer - one who liked crunching tackles. You don’t ever forget having really great players in your team.”

Lovell was involved in big triumphs over Hearts, the millennium derby and 6-2 in 2000, the year he won his two caps. “Both came at a tournament in Dubai. After the first game against Kuwait, the guys asked the manager, Frank Farina, if we could have a night out. ‘Be back by 4am,’ he said, which was pretty generous. But I’m embarrassed to say we overshot the curfew. I’d flown across with Tony Vidmar when we’d got chatting to a couple of the stewardesses, girls from Wales. Viddy was more clued-up than me and he’d grabbed a phone number. The team and the Emirates crew all ended up at a house party. Shuffling back to our hotel at 7am in time for breakfast wasn’t what I imagined international football would be like!”

But Lovell’s disappointment the following year at not starting that final against Celtic was “the biggest kick in the teeth of my career.” He’d been a regular all season only to lose out to Ian Murray. “Ian was better defensively than me, no doubt about that, but I was angry. I said to Alex: ‘Do you want to win the game or are you just trying to keep the score down?’” Hibs also had to do without Latapy, banished for partying with his pal Dwight Yorke. “That seemed to be Alex saying ‘Look how strong I am as a manager’ but it was the wrong decision. The chances of us beating Celtic without Russell weren’t diminished by ten per cent - it was more like 50.”

A couple of times today Lovell checks himself. His omission was a “shock” but how shocking, really, next to the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation? “I don’t want to be defined as a footballer,” he insists. “When I was playing I’d hear old pros talking about how the game wasn’t as good as in their day. I vowed I wouldn’t become embittered like them. We’re a long time on God’s green earth. When one thing’s over, why not do something else?”

For him that’s Street Soccer Scotland. “‘Come and play football’ is a powerful message when your life has been full of chaos and trauma and it’s incredibly rewarding being able to see how something so simple and yet so brilliant can provide structure and boost self-esteem.” The charity is established in the four biggest cities and it’s Lovell’s job is to grow the charity beyond them. He hopes potential benefactors will read this interview and want to help.

But Stuart Lovell was a footballer once and he isn’t about to forget the joy it brought him. The joy, after walking away from European competition with Hibs, of then achieving Uefa Cup qualification with Livingston. And the joy of Hampden glory when, though he rejects such a notion, the League Cup seemed to be the club’s destiny.

“We’d just been hit with administration and had to watch as team-mates, colleagues and friends lost their jobs. After the semi, there was no singing in the dressing-room - you wouldn’t have known we’d won. Come the final, though, we knew what we had to do.”

Get a year of unlimited access to all of The Scotsman's sport coverage without the need for a full subscription. Expert analysis of the biggest games, exclusive interviews, live blogs, transfer news and 70 per cent fewer ads on Scotsman.com - all for less than £1 a week. Subscribe to us today

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.