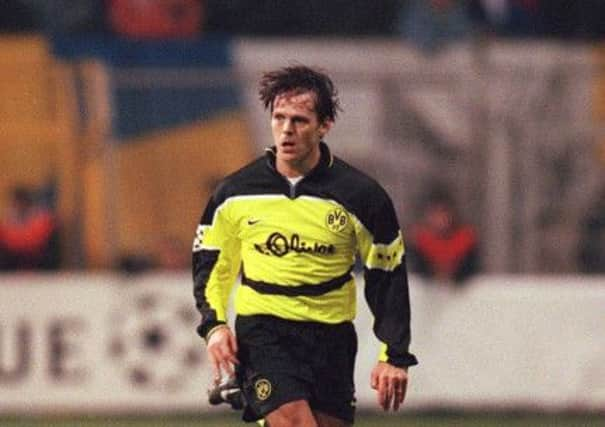

Scott Booth relives German glory days

Booth spent much of his two-year Dortmund career on loan – to Utrecht and Vitesse Arnhem – but he played, and scored, for his employers in the Champions League, and he was among the substitutes when they became unofficial world champions, beating Cruzeiro 2-0 in the final of the Intercontinental Cup.

Last week, as Dortmund again made Europe sit up and take notice, moving to within 90 minutes of another appearance in the continent’s showpiece club competition, it reminded Booth of the quality he was suddenly exposed to 16 years ago, a culture shock that brings a smile to his face even now.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“You were basically taking me out of an average Aberdeen side and putting me in with Andy Moller, Jurgen Koller, Matthias Sammer, Karl-Heinz Riedle, Stephane Chapuisat… too many to mention. You’re going in there thinking ‘what is this all about?’ The standard was so high that, for me, even training was like playing in a cup final. In order for me not to look stupid, I had to play at my best every single day.”

Booth, who now works for the Scottish Football Association as an assistant coach to the country’s youth teams, is pleased to see that standards are again high in Dortmund, that the Ruhr Valley is once more home to some of the world’s finest players.

This time, though, there is a difference. While Riedle, Sammer and Koller were expensive, proven internationals, signed from Lazio, Internazionale and Juventus respectively, it was a young, cheaply-assembled team that thrashed Real Madrid 4-1 in Wednesday night’s semi-final first leg. Most of them were German, and some of the stars – such as Mario Gotze and Marco Reus – are a product of the club’s own youth system. “For a club that was virtually bankrupt to get back to where they are, this time with really good, young players is an amazing achievement,” says Booth.

Dortmund nearly went into liquidation in 2005. The very ambition that had paid off in the late 1990s brought them to the brink of extinction. Like the rest of German football, which was stung by the national team’s failure at Euro 2000, they set about finding a new, more sustainable way forward in which they could make stars, rather than buy them. Their victory last week, coupled with a similarly stunning result for Bayern Munich against Barcelona, suggests that they have done an admirable job .

If Germany is emerging as the dominant force in European football, it is not by accident. When the country’s administrators sat down in 2001 to rip it up and start again, the outcome was a new licensing system for the Bundesliga in which every club had to invest in a youth academy. Strict rules were laid down to ensure that clubs would be run by members rather than filthy-rich benefactors willing to run up a debilitating debt. Ticket prices fell, crowds rose and, little more than a decade later, there is a vibrant, competitive league on a relatively level playing field.

“Right now, the German league is very, very strong,” says Booth. “They are playing best against best all the time, at a high tempo week in, week out, which means that it is so much easier to make the transition to a Champions League game. They’ve put a lot of hard work into revitalising their football, and now it’s paying dividends.”

The improvement has manifested itself in the national team, which has been invigorated by a new generation. Their dynamic, fast-breaking athleticism is inspired by the clubs, many led by young, imaginative coaches schooled at the same Cologne training centre.

If the Champions League semi-finals are any guide, the much-vaunted tiki-taka is in danger of being buried by a more positive, dare we say, old-fashioned emphasis on energetic attacking. Booth, whose Scotland under-15 side lost 2-0 to Germany last month, says the same physical and mental strength is apparent in their national youth teams.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We did well against them, don’t get me wrong, but they definitely have a greater maturity about them. Most of their players were bigger and stronger. Even the smaller ones seemed to be more in tune with their bodies, more comfortable and assured. At 15, they already know how to win, how to handle different situations.”

While it would be asking a lot of Scotland’s clubs to invest £700m in youth academies, as Germany’s have in the last decade, Booth believes that they should take inspiration from the Borussia Dortmunds of this world. The German club and its Bundesliga rivals, who came together at a time of need, are now reaping the benefits.

“We can get there definitely, but everyone needs to buy into it and put aside the little grievances from the past.

“Football in Scotland needs to be strong again and the only way you can really do that is by bringing through your own young players. It’s the only affordable way.”

For all its success, there is a theory that the German model is destined to be short-lived, that it must, by definition, be corrupted by its own success. Bayern, for instance, have won this season’s title at a canter. On that basis, they will be favourites to win the Champions League and, in so doing, become even more powerful. They are already threatening to demonstrate their financial muscle by purchasing one, maybe two, of the players who have been vital for Dortmund.

Booth, though, is more than happy to give Germany the benefit of the doubt, not least because this is Bayern’s first title in three years. The form this season of Freiburg and newly-promoted Eintracht Frankfurt is also a tribute to the Bundesliga’s growing strength in depth. “Given the competitiveness of the league, there is less chance of anyone running away with it year in, year out,” he says. “Every now and then, you will get a great team that just clicks, but they have put in place a system that gives other teams a chance. Yes, Bayern are getting stronger, but it doesn’t mean that the others are getting worse.”