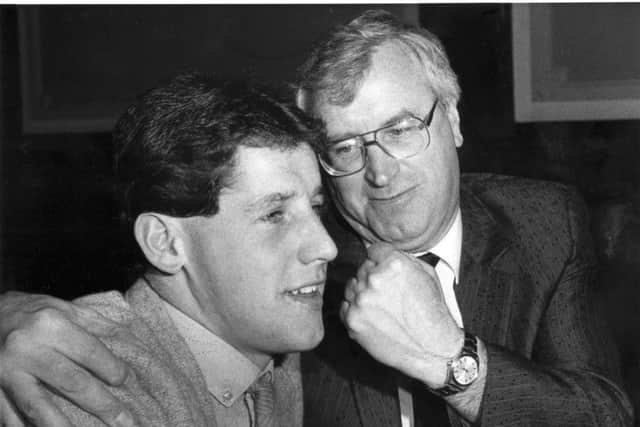

Interview: Queens and Rangers legend, Ted McMinn

On the back of an old cigarette card, Ted McMinn’s style might have been called seat-of-the-pants. And it’s not a bad description given that no one really knew if he was going to dump a full-back on his backside or attempt one shimmy too many and end up in that situation himself. But it suggests that football came easy to the big winger, that he just daundered into the game without a backwards glance. Nothing could have been further from the truth.

As an example of the crazy dramas of his life, the humour and the sadnesses, take the day McMinn found out he was switching from his hometown team to his boyhood heroes: “It was early one Sunday morning and I’ll never forget it,” he says. “The only people who ever knocked on our door were the police looking for big brother Martin because he’d pinched a motorbike or hot-wired a car and you never saw four boys scatter so quickly. Eventually Mitchell was nominated to answer it. He saw these two serious-looking guys in hats and ties – detectives? – and instead of ‘Hello’ he said: ‘What do you want?’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Mitchell came and found me. I was thinking: ‘What did I do? Break a window? Hit a car with a golf ball?’ But it was Willie Harkness, the Queen of the South chairman, and his brother, Sammy. ‘Hello Ted,’ they said, ‘we were wondering if you’d be all right to take a wee trip to Glasgow.’ I said: ‘But I’m due at the sawmill.’ They said: ‘I wouldn’t worry about work, son – you’re signing for Rangers.’

The McMinn boys were home alone because their father was at his work, as he’d been pretty much all the time since their mother had walked out on the family, often putting in 18-hour shifts to provide for them. Ted, only six when she left, was too embarrassed to invite his chairman into their Dumfries flat as five males could never keep the place clean. He was so excited, though, he thought he was going to burst. “I wanted to run down the stairs and right round our scheme to tell everyone. I went to the sawmill, told them. They were like: ‘What are you thinking about, packing in your job for Berwick Rangers?’ ‘No, not Berwick, the mighty Rangers.’”

I’m talking to McMinn, the Tin Man himself, in his Derby home because tonight the reduced Rangers are at Queens for the start of the Premiership play-offs. “This’ll be a tough one for me because I love them both,” he says. But his story does not need the hook of such a game and would be worth telling at any time. Queens, Gers, Sevilla, Derby County, Birmingham City, Burnley, Joondalup of Australia, Slough Town – these were the staging-posts of a quixotic football wanderer and for every manager like Graeme Souness who ran him out of town there were usually two who loved him as they would their son (Jock Wallace, Arthur Cox).

The career stats also include four wives and one leg. But at 52 he’s found happiness at last with Marian and a sense of purpose and worth with his first full-time job since having to undergo amputation. “I work at a special needs school, St Clares, doing the handyman stuff and a bit of PE. I’ve marked out a football pitch and usually get roped into the games, which can be tough, because I’m only supposed to be on my artificial leg for a couple of hours a time and when I get home I’m knackered. But it’s a fantastic job and I love it. The pupils think I’m amazing because I can still play, after a fashion, and some would probably say I wasn’t much better when I had the two legs. But the kids are even more amazing and a wee reminder there’s always some people worse off than yourself.”

Aged six, though, McMinn would have been forgiven if he thought no one had it as bad. He remembers returning from an errand and seeing his mother, Evelyn, standing across the road from the family home on Dumfries’ Lochside estate, suitcase by her side. He waved but she didn’t respond, and that was the last time he saw her.

“Dad had to raise us on his own. He worked so hard as a fitter at the ICI plant but four hungry boys just devoured everything. We lived off crisps and lemonade. Sometimes we didn’t eat from one school dinner to the next. We’d pinch the Spam from his piece-tin. We’d pinch milk from other people’s doorsteps. We’d wait for the tide to go out at Hestan Island and come back with seagulls’ eggs and get our granny to make us a sponge cake. The big treat was Friday night when Dad would buy a sausage supper and we’d get his chips.

“I should say there were folk in that scheme who knew our situation would let us stay for tea. The teachers were sympathetic too, but because Dad was always working he couldn’t always make sure we went to school and often I didn’t. I’d try and forge my report cards, and if they said I’d only been there 11 times, stick a 1 in front – but not being the brightest it would be in a different-coloured pen. It felt like my brothers and I were the only broken-home kids in the school and I was pretty sure I was the only asthmatic. I was perpetually nervous in class, a wee worrier, so really I was never going to get an education.”

He could, though, play football, inhaler hidden in a sock, and his mum got in touch after he signed for Rangers. “I wrote back saying I didn’t have a mother and told her not to contact me again. She tried again at Derby but Arthur Cox, who knew my story, sent her away. Dad, to be fair, although he’d suffered, would say, ‘It’s up to you if you want to speak to her,’ but I always thought I’d be betraying him if I did. If one of my brothers told me she was dead I wouldn’t be bothered. That may sound harsh and horrible but it’s the way it is.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s ten years since McMinn lost his right leg just below the knee after the ravages of a mystery infection and 20 this month since his father died, so 2015 could hardly be more poignant for him. William Wallace McMinn seems to have instilled a deep patriotism in his second-youngest, who says: “My biggest regret was never winning a Scotland cap. I’d like to think I might have played in the 1990 World Cup, but I did my cruciate and was out for 14 months. I’m incredibly passionate about Scotland. Every time I hear the anthem I have a wee greet.” The old man, though, wasn’t really a football man.

“I remember Dad coming to one of my amateur games after pals at his work told him I wasn’t bad and him letting the dog drag him away from the side of the pitch. He always had binoculars with him and claimed he could still see me from this hilltop. Come to think of it, he always had the dog with him, too, even at Queens games. There was one against Stirling Albion where I got sent off. As soon as that happened, the dog and him wandered off, thinking I’d be straight out to see them. When I told him about Seville and that I hoped he’d come see me play, he still wanted to bring the bloody dog.”

If that sounds like eccentric behaviour, his son more than matched it on the park. Ungainly? Infuriating? The daftest of Scottish wingers and that’s saying something? McMinn laughs off the charges. Graeme Souness famously pronounced him uncoachable, as he never knew what he was going to do next. “It’s true, I didn’t, but then what player does?”

Maybe turning down £80 a week at Kilmarnock could also be deemed eccentric but Queen of the South, where McMinn earned less than a third of that, were his team. “As a boy, passing Palmerston when the floodlights were on, I always thought: ‘Bloody hell, I’d love to be playing there.’” Unable to afford the admission, he’d nip in free for the second half, and hope by the 85th minute to have secured a complementary pie, no matter how crusty-black. Awayday round trips to Brechin took 17 hours and were cheerfully endured. And when in 1982 Drew Busby, Queens’ manager, turned him from a fan into a player he was thrilled to be able to walk into town after games to take the acclaim (or abuse) from his old school chums, rounding off the night at the Oasis discotheque and a Chinese takeaway for the trudge home.

The player who clattered into Ibrox two years later was, he admits, a “country bumpkin”. He fell for the ruse of ordering sirloin steak for his first match-day meal. “Listen, son,” growled Jock Wallace, “I don’t know what it is was like at Queens, but here you’ll have scrambled eggs on f****n’ toast like everybody else.” Suddenly, though, he was sharing the Deep Heat with the great David Cooper himself. Wallace became his mentor – “A wonderful guy who was great to me.” The old nerves hadn’t left him and never would – “Before every single game, when the five-minute bell sounded, I’d be sick.” His first goal as a Ranger came when he worked a Boghead hurricane to his advantage to score direct from a corner – typical McMinn. The only problem was the not insignificant one of home crowds as low as 12,000.

Exit Jock, enter Souness flaunting designer threads from Italy. “He asked me where I got my suit. ‘Burton’s,’ I said, thinking it was quite a good make.” But McMinn was soon reduced-to-clear, a couple of wild nights out, including a notorious one in East Kilbride with Ally McCoist and Ian Durrant, persuading the exasperated boss to sell him to Sevilla for a reunion with Wallace at a knockdown price. “The other two were stars whereas I was just the boy from Dumfries, so I was expendable.”

By this point McMinn was already on his second marriage, the one which produced his two children, Dayna and Kevin. About his failings as a husband and father, he’s brutally honest: “Early on I was way too immature and selfish. I didn’t expect to be asked what time I’d be home, or what day. I was frightened of being hurt by a woman like Dad had been, so I couldn’t settle down with one without having a plan B. So did I walk away because my mother had done that? It’s not really an excuse but at least I’ve always been there for my kids. Jackie, June and Sue, who came before Marian, were all brilliant – the only b*****d in this story is me. Dad was upset when my marriages ended. ‘Son, you’ve got to treat women better,’ he said, ‘otherwise you’ll definitely end up on your own.’”

Being of similar age and having done national service with the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, McMinn’s father and Wallace got on famously on the former’s trips out to Spain, without the dog, to see El Tin Hombre in action. And player and manager couldn’t have been closer by that point, not least on the night they pretended to be gay. “We went hand in hand across this park where there had been a few cases of rape because couples weren’t attacked. We were pissed but managed to get to the other side okay, but when we found Jock’s car the window had been smashed and the radio nicked. He got in, still determined to drive. ‘Something’s still not right, Ted’ he said. I said: ‘Gaffer, you haven’t got a steering wheel anymore.’ We hailed a taxi and I’ve always thanked that thief.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut this closeness led to their undoing in La Liga. The rest of the team, all local, resented it, not least when World Cup star Francisco was axed and Wallace gave McMinn his shirt number. “Maybe the final straw, though, was when he clamped down on the pre-match meal. The players were used to soup, salad, steak, fish, then dessert. Jock told them to cut out one of the main courses. Me, I was the weirdo who always had an omelette.”

A decade on, the loss of his leg continues to baffle McMinn but no longer haunts him. Was the infection a legacy of cortisone injections, a tussle with a horsefly or the time he waded through a swamp in Corfu? He still doesn’t know. “The infection count in my blood was 336 – normal is nine.” There were five operations in five hellish weeks. When surgeons tried to scrape away the diseased part, the bones crumbled. They folded over the sole of his foot so it “looked like a samosa”. Hugely frustrated and unable to move without pain, he remembers crying on a fishing trip having nearly fallen in the pond and thinking: “I’m useless. I can’t carry on like this.”. So, to the doctors who’d told him amputation would give him a better quality of life, he said: “Do it.”

At first the disability was tough. “Having been a footballer, right up there, it was quite a crash.” He convinced himself this was payback for having been such a scoundrel. “Someone somewhere was sticking pins in me.” Watching football, the game he played with such awkward enthusiasm, was difficult. “If there was a bad tackle I’d get these phantom pains in my leg.” But all of this, thanks to Marian, the job and becoming a grandfather, has got better.

He thinks back to when he hung up his boots. His father, who phoned him every Saturday without fail, was no longer around. The body was creaking. “Then suddenly, for the first time ever before a match, I wasn’t sick. I knew it was all over.” What would Dad make of him now? “I’m sure he’s been looking down all this time, with his binoculars of course. He’ll be glad I’m happy, even though it’s taken a long time. But even though life was tough for us McMinns when we were growing up he did his absolute best.”

Then Tin Man laughs. “Do you know I still don’t know how to put on a tie? Marian does it for me now, my son used to do it when he was a wee boy and before that Dad did it. I’d be going off to a Queens game, he’d be in bed having worked the nightshift and I’d have to wake him. Fumbling about in the dark he’d sometimes not do it right and I’d have to go back and get him to tie it again. I remember him tying it the day I signed for Rangers, him insisting on driving me in his old jalopy when Willie Harkness had offered us his Mercedes. When we got to Ibrox there was a tear in his eye. It was the most emotional I’d seen him since Mum left. ‘I’m very proud of you,’ he said. ‘This is every father’s dream.’ He’s my hero, you know.”