The Old Firm story: Jock Stein becomes Celtic's saviour

By the beginning of 1965 there was a common perception of Celtic. It was considered a club with a great past, but no great future. As yet another season prepared to slip by without Celtic making a serious challenge for the championship, it condemned the club to endure 11 seasons without a title success. Never before – and not since, indeed – has the club been separated for so long from Scotland’s most coveted prize. When it came to the sparring of the Old Firm, Celtic had become heavyweight Rangers’ punchbag.

The Parkhead club were still capable of producing outstanding players. A raft of prodigious young talents – headed up by Billy McNeill, Jimmy Johnstone, Bobby Lennox and Bobby Murdoch – were on their books. These players were also capable of outstanding results, with the last weekend in January bringing an 8-0 hammering of Aberdeen. What the club was not capable of doing, as a consequence of an autocratic chairman, Robert Kelly, imposing some inexplicable team selections on mild-mannered manager Jimmy McGrory, was winning trophies.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe day after the mauling of Aberdeen, an announcement was made that would change everything for Celtic, and indeed Scottish football. It came in confirmation that Jock Stein, the former double-winning Celtic captain and reserve coach at the club, would be leaving the Hibernian post he had held only for months to become Celtic manager that summer.

As it transpired, Stein made the move in the March. His last game in charge of the Easter Road side ousted the country’s dominant Rangers side from the Scottish Cup. The outcome proved to have huge significance. It helped smooth the way for the newly arrived Stein to snare Celtic their first major trophy in 11 years, courtesy of a 3-2 victory over Dunfermline. The symmetry was unmistakable: three years earlier he had helmed the East End Park side as they outfoxed Celtic in the competition decider.

The 1962 triumph spoke of the scent for silverware and the sense for seizing in Stein. His feats for Celtic shouted these talents from the rooftops. All this would have happened earlier than 1965 had Kelly be able to relinquish powers that never ought to have been his. The Celtic chairman did so as the option of last resort, and hid behind the claim that he was worried about Celtic supporters not accepting a Protestant as manager. Stein had left Celtic for Dunfermline as he felt he had “gone as far” as he could as Celtic’s three managers were all Catholic. He forced Kelly’s hand when telling him of an offer from Wolves. Even then he was initially offered assistant to Sean Fallon, and joint managership with the Irishman before Kelly had to acquiesce to Stein’s bottom line of full control on all football matters.

McNeill has talked of Stein’s third coming at the club – and it was very much that for the players he coached and crafted in the younger ranks – as being akin to the switching on of a light. In reality, his impact on Celtic was equivalent to removing the club from a permanent eclipse and allowing them to bask, for an age, in a summertime midday sun. Stein’s brilliance brought a blinding illumination to the Scottish game it will never again be cast in.

Stein was shrink and sergeant major, sage and sorcerer to his players. The former miner from the same Bellshill area that produced Matt Busby and Bill and Bob Shankly could extract the fuel that fired these talents as once he hewed coal – his tactical nous and technical expertise his principal tools in a kitbag bursting with them. Using his imposing frame, he could also be as brutal to players, referees and media as was his former life at the coal face.

It hardly does justice to talk of his 13 years in charge as yielding a European Cup, a then record run of nine consecutive titles, one more championship thereafter, eight Scottish Cups and six League Cups (a meagre return from that tournament considering that Celtic contested every single final of his 13 years). It wasn’t simply about the winning, which in the late 1960s was sometimes with slender margins from an excellent Rangers side. It was the swashbuckling style in which this was achieved that makes Stein both The Big Man and Celtic’s giant to dwarf all others for feats achieved while based in this country.

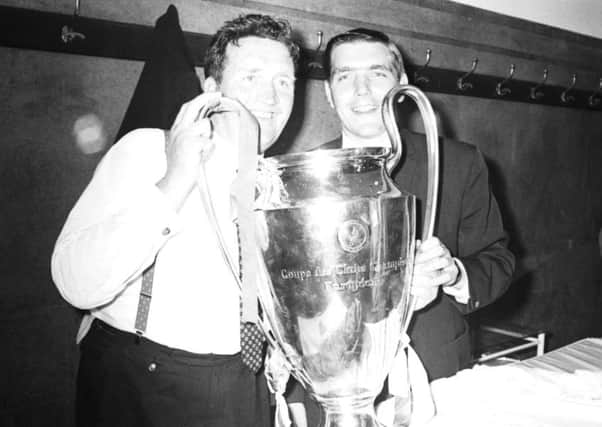

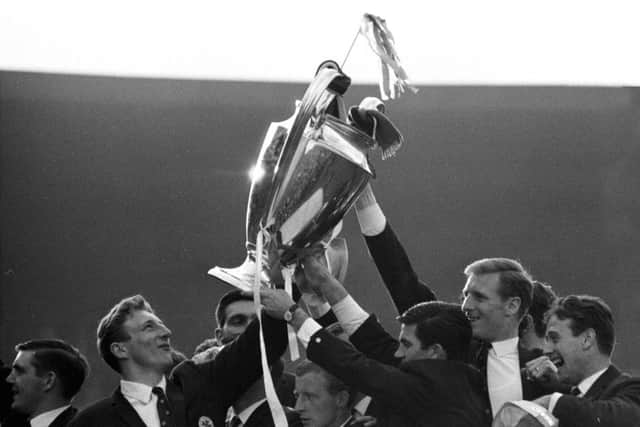

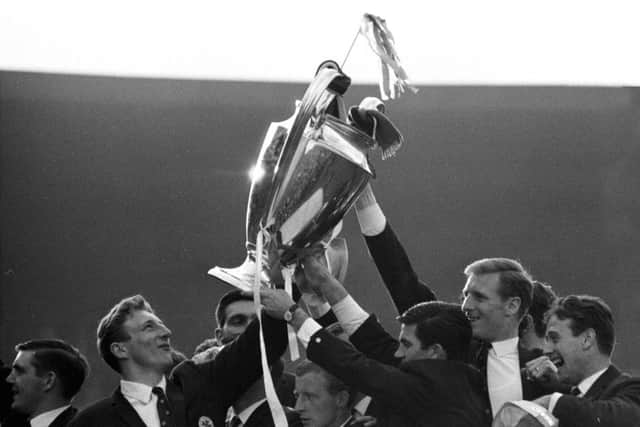

All roads inevitably lead to Lisbon when setting out Stein’s magisterial management abilities. The 1967 European Cup final victory over Internazionale that made Celtic the first non-Latin side to win the prized club tournament then more then a decade old,and being held hostage by suffocating defensive play, has few equals in its history.

Never before or since has the European Cup/Champions League been won by a team producing more than 40 goal attempts. The fact that all Celtic’s players were born within a 30-mile radius, is also without parallel among winners. For the most stirring evocation of the 2-1 win in the Portuguese capital on 25 May, 1967, the words attributed to Stein are impossible to better. “There is not a prouder man on God’s Earth than me at this moment. Winning was important, but it was the way that we won that has filled me with satisfaction. We did it by playing football; pure, beautiful, inventive football. There was not a negative thought in our heads.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome negatives though do arise when assessing Stein’s Celtic years. He allowed complacency to develop among the squad after they had beaten Leeds United to set up a European Cup final against Feyenoord in 1970, a loss of that prevented his Celtic team truly cementing their greatness. Yet, with one win, one other final, two semi-finals, and two quarter-finals in the European Cup over an eight-year period, Celtic equalled Bayern Munich’s current standing in club football’s most prestigious tournament.

It was not nature but a car crash in 1975 in which he almost died that robbed Stein of his edge. In three of his last four seasons, Rangers were champions. Trebles the Ibrox side claimed in 1976 and 1978 helped shatter the aura around Stein. These landmarks sat alongside the Cup Winners’ Cup triumph of 1972 as successes to savour from the decade.

Celtic’s failure even to earn a European place in 1978 – one year after Kenny Dalglish’s last acts as a player at the club were to spearhead a double success – persuaded Stein to step down. He did so believing that as well as choosing successor Billy McNeill he would be appointed to the board of directors and given a football-related role. Instead, he was offered the insulting position of director within the club’s pools operation. He could only refuse, moving to Leeds United before leaving inside seven weeks to become Scotland manager.

His death in the dug-out as Scotland played out the final seconds of the September 1985 win in Cardiff that secured them a place in the World Cup finals gives cause to reflect on one of Stein’s many profundities.

“We all end up yesterday’s men in this business. You are very quickly forgotten,” he said. Stein wasn’t wrong about much, but he indubitably was about that. Stein, who he was, and the wonders he worked, will always be projected into our tomorrows.