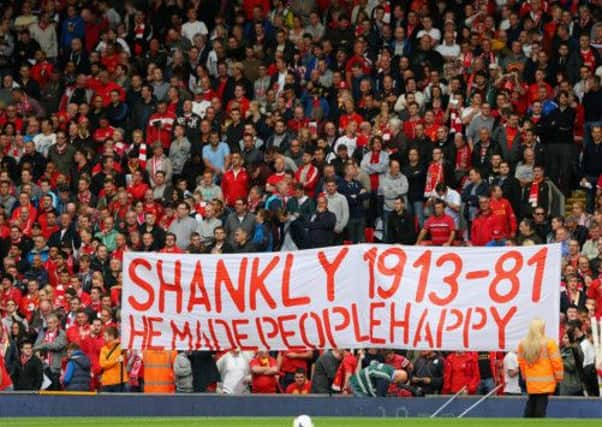

Bill Shankly’s legacy lives after 100 years

Such relationships were important in the mining villages which dotted Ayrshire but have, since the coal was mined out, died.

Glenbuck, Burnfoothill, Corbie Craigs, Darnconner, Burnieknowe, Cronberry, Torhill and Rankinston grew up around workable coal reserves and as in the case of all but Cronberry and Rankinston, vanished once the coal was worked out.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdExotically-named football clubs are a feature of Ayrshire football: Burnfoothill Primrose, Rankinston Mountaineers, Cronberry Eglinton – Shankly’s old team – and, most-memorably, Glenbuck Cherrypickers, have gone. Craigmark Burntonians, Kilbirnie Ladeside and, of course, Auchinleck Talbot survive.

The book Cairntable Echoes – which is made up of snippets from the archives of the Muirkirk Advertiser – includes a short piece on local football in the 1930-31 season. It reads: “The resuscitated Glenbuck Cherrypickers opened their season with a resounding 3-2 victory over Cronberry Eglinton at Burnside Park. Team – Bertram, Thomas, J Brown, J Tait, A Brown, Menzies, Miller, A Tait, Shankly, Miller and Bone. The team went on to lift the Ayrshire Cup, beating Lugar Boswell Thistle 1-0 in a replay, in what would prove to be their last-ever game.

Given that all his older brothers – Alec, Jimmy, John and Bob – had already joined the senior ranks, that Shankly, listed at centre forward, has to be Willie Shankly. He may have started the season with the Cherrypickers, but he finished it with the opposition, Cronberry Eglinton, from whom, at the start of the following season – with Eglinton folding – he went senior with Carlisle United.

His upbringing in Glenbuck, a village which was already dying when he was born there, 100 years ago today, on 2 September, 1913, at Number 2, Auchinsilloch Cottages cast a long shadow over Shankly’s life and beliefs. In places such as Glenbuck there was an oft-asked question: “Who’s he for – a Shankly, or Smith, or Brown?” This was because, most of these small mining villages did live up to Donald Finlay QC’s description of a typical Scottish mining village: “3000 inhabitants – four surnames”.

With so many extended families living there, it was not unusual to have the same surname repeating itself along each of the miners’ rows of houses, so it was important to know which of perhaps ten or more Alex Browns or John Taits was being spoken of.

However, this closeness paid dividends in the dark and dangerous coal face, where brothers would look after each other, as would cousins and second cousins; an esprit de corps, a sense of togetherness closer than in even the most disciplined of army regiments or ships’ companies, helped the men at the coal face get through each difficult shift. Then, of a weekend, the same closeness worked in the strips of Glenbuck Cherrypickers, or Auchinleck Talbot, or Muirkirk Athletic. Shankly always strove to have that sort of togetherness in his teams. They watched each other’s backs and the player who couldn’t or wouldn’t fit into his idea of recreating the togetherness of the pit never lasted long.

Another carry-over from Shankly’s upbringing was the way he made players earn their place. As a 14-year-old, leaving school to go into the pits, Shankly wasn’t immediately sent to the coal face. He started at the pit-head, then went underground; even then, he would have to earn the right to a place at the coal face. He would have to prove he fitted in, that he could do the still difficult, but nonetheless “easier” work of clearing-up, hauling the coal from the face to the pit bottom, before he would be permitted to actually hew the black diamonds from the thin seams of the East Ayrshire coalfield.

That same system operated at Anfield. Even such gems as Kevin Keegan and Emlyn Hughes had to serve an apprenticeship in the reserves before being handed a first-team jersey.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShankly never forgot from whence he had come. My uncle Willie had been his “mucker” down the pit – contemporaries in ages, they worked as a pair. Shankly escaped the pit to play football, Uncle Willie, known locally as “Crilly” after 1920s Celtic player Willie Crilly, escaped to drive trucks. One night in the early 1970s, he found himself having to overnight in Liverpool, who were playing a European Cup tie at Anfield that night. In spite of not having spoken to Shankly in over 30 years, he impulsively telephoned the ground, was put through to Shankly and bagged a seat in the directors’ box for the game, plus a reunion with Shankly in the famous Boot Room.

One of my cousins, Allan Ross, played for many years as goalkeeper for Carlisle United, and still holds that club’s appearance record. Allan’s mother, my Aunt Elsie, was a teenage friend of Shankly – indeed, they went out together. After playing for Carlisle at Anfield, Allan approached Shankly with the opening line: “You might have been my father”. Shankly asked how this might have been and, on learning of the connection, immediately asked after Auntie Elsie and her family. He had remembered the names of all seven of Crilly’s sisters. However, on being called away, he had a sting in the tail for Allan, telling him: “Son, if I had been your father, you’d have saved our third goal”.

Shankly had survived in the tough world of the Ayrshrie juniors as a teenager, so he was willing to give youngsters a chance, if he thought they were good enough; as assistant to Andy Beattie at Huddersfield, he pushed the case for early first-team action for a whippet-thin 16-year old Aberdonian named Denis Law…the player he most-wanted to sign for Liverpool, but, was unable to persuade the directors to pay for.

One carry-over from his mining days might have told against Shankly today. He knew how hard life at the coal face was. He appreciated how lucky he was to have had the football talent to escape life underground. He felt it was a privilege to be able to make a living from kicking a football around. So, like those other iconic former miners turned football managers – Matt Busby and Jock Stein – he was disgusted by some of the demands of players, keen to cash in on the potential new riches offered by the abandonment of the maximum wage in England in the early 1960s. Some of the wages being demanded by players who, in his eyes were not fit to lace the boots of his great favourite, Tom Finney, grated with Shankly. He might have found it very hard to work in today’s “money is no object” English game.

Shankly’s road to greatness was long and tough – Glenbuck, to Cronberry, to Carlisle United, to Preston North End and Scotland, fame and glory. His best footballing years were lost to war; but, he moved on, to playing and coaching at Preston, then to management at Carlisle, Grimsby, Workington and Huddersfield Town, before he found his niche and true greatness at Liverpool.

He took a big club, which had fallen on hard times, and rebuilt it, making it greater than ever. He had huge self-belief, which he transferred to the Liverpool club – with such iconic ideas as the “This Is Anfield” sign above the tunnel entrance. He was a 20th century Spartan, totally dedicated, not to warfare, but to football.

But, he died an unhappy man. His sudden resignation from Liverpool, perhaps in a bout of depression, has never been explained. Without the daily involvement in football, he was rudder-less. He died too soon.

Glenbuck, where it all began, is dead too now. All that remains to indicate there was once a village there is a signpost on the A70, a tarmac road which peters out, some kerb stones and a bit of wall. Where Glenbuck once stood there are now some abandoned buildings and plant from a closed opencast. It looks like a moonscape or a bomb site.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe spirit of Shankly survives, in the gleaming black memorial stone, outside the entrance to what was once Glenbuck House and in the happy memories of the players he inspired and the Koppites who saw him as a father figure.

With Willie “Bill” Shankly on their side, they never walked alone.

Today, on the 100th anniversary of his birth, we should remember Ayrshire’s Number One football man – because, like that county’s number one poet, his memory is immortal.

In quotes: some Shankly classics

• “Some people believe football is a matter of life and death. I am disappointed with that attitude. I can assure you it is much, much more important than that”

• “If you are first you are first. If you are second you are nothing”

• “If Everton were playing at the bottom of the garden, I’d pull the curtains”

• “The trouble with referees is that they know the rules, but they don’t know the game”

• “Of course I didn’t take my wife to see Rochdale as an anniversary present, it was her birthday. Would I have got married during the football season? Anyway, it was Rochdale reserves”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad• “At a football club, there’s a holy trinity: the players, the manager and the supporters. Directors don’t come into it. They are only there to sign the cheques.’’

• “If a player is not interfering with play or seeking to gain an advantage, then he should be’’Shankly on the offside rule

• “If you’re not sure what to do with the ball, just pop it in the net and we’ll discuss your options afterwards’’ Shankly’s advice to Ian St John

• “It was the most difficult thing in the world, when I went to tell the chairman. It was like walking to the electric chair.”On leaving Liverpool

• “Just tell them I completely disagree with everything they say” To a translator when being surrounded by gesticulating Italian journalists

• “I was only in the game for the love of football – and I wanted to bring back happiness to the people of Liverpool”