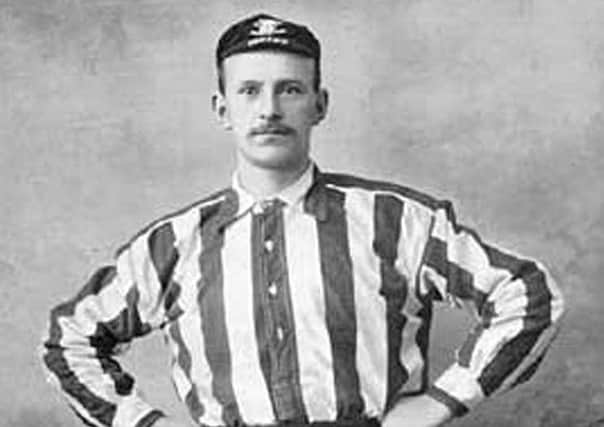

Remembering Ned Doig, Scotland’s Prince of goalkeepers in Sunderland’s ‘Team of all the Talents’

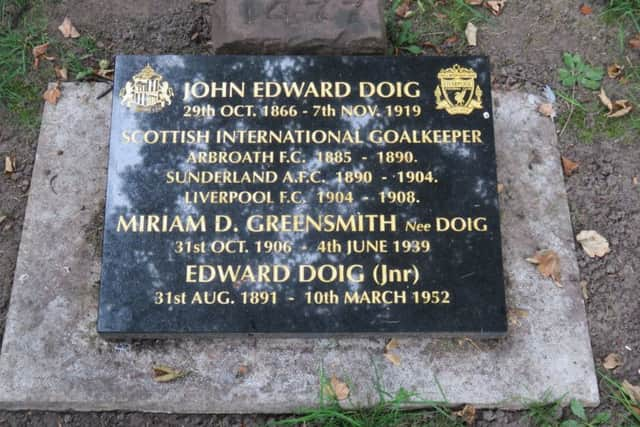

Tomorrow, it will be 100 years since John Edward Doig died. He was laid to rest in plot 1477 of Anfield Cemetery. Chiselled into the modern, gleaming plaque settled on his grave are the club badges of Sunderland and Liverpool, beside his name and above the inscription: SCOTTISH INTERNATIONAL GOALKEEPER. Two of he and wife Davina’s eight children, Miriam and Edward, sleep beside him. For many years, the burial plot was unmarked – family efforts remedied that travesty. Some don’t forget.

The grave is just about equidistant between Anfield stadium and Goodison Park. Doig, known to all who followed football as ‘Teddy’ or ‘Ned’, had signed for the Reds in 1904. He was, by then, 37 years old, with a palmy and revered career behind him. Ned Doig played on at Anfield for four years. He is still Liverpool FC’s oldest-ever footballer.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt started in Arbroath. Young Ned, a teenager from the Letham sticks, begged three wooden beams from a shipyard and constructed his own goal frame. There was some interest for a while in an outfield posting – he started at outside right for local club St Helena – but the act and artistry of stopping the ball going into the net soon transfixed Doig.

He trained as if preparing for a montage sequence in the movie of his life. A leather football was strung from the timber crossbar on a length of nautical rope. Doig, ambidextrous when writing, learnt to punch so hard with both hands that it would loop twice around. Adult interlopers could manage only one circuit. Later, when a professional player, he was able to thump the ball to team-mates lodged on the halfway line, a feat only otherwise achieved by the legendary – and remembered – William ‘Fatty’ Foulke. Further, Doig made his own dumbbells in a local foundry, rested one by each post and dashed from side to side, grabbing and lifting the weights.

Though Doig would only ever rise to 5ft 9in tall, this eccentric regime forged agility and a strapping physique. In the Arbroath Sports Day of 1888, he won the high jump, 300 yard sprint, skipping race, hop step and leap and hoofed the ball more than 50 yards to take the place-kick title too. By that time, he had already won a cap for Scotland.

It is likely that Ned Doig was in the crowd when Arbroath defeated Bon Accord 36-0 in 1885. History seemed to follow him around in that manner. He was certainly at Gayfield for a game with Dundee Harp in February 1886. That day, with regular goalkeeper James Milne suddenly unavailable, a crowd member hollered ‘Let Ned Doig play!’ His prowess had been noted across town and by the Red Lichties. He was summoned and readied, the civilian changing into his superhero outfit in a phonebox. Doig’s debut ended in a 3-2 loss to Harp.

Even so, he managed to stand out, The Arbroath Herald remarking how his ‘skilful and dextrous movements’ were ‘the talk of the match.’

Defeats and conceding in multiple were not something he would grow accustomed to. Word spread of an almost unbeatable young goalkeeper, a supple, unflappable junior Hercules.

Though spry and mobile, Doig could be a boulder when necessary, resisting the violent charges of opponents. To be a custodian in Victorian times was to be an object for barging and bundling. He was, appropriately for Arbroath, a lighthouse in a tempest. Doig was noted, too, for his emphatic and accurate kicking, his feet becoming weapons for sweeping up and launching forward play, that habit so venerated currently.

The Scotland selectors telegrammed in 1887. Doig’s first cap came just after his 21 st birthday in a 4-1 victory over Ireland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSunderland were Scottish in all but location. Since their foundation in 1879, they had looked north for players and strived to perform in the Scottish manner of what counted then for pass and move. It was natural and obvious that they should tempt the country’s best goalkeeper to Wearside. Newly married to Davina in the summer of 1890, Doig left his job as an insurance clerk and the two swapped one North Sea port for another. The move into English professionalism placed a halt on his international career – until the mid-1890s, the SFA refused to call up players who had gone south to earn a grubby living by being paid for their skill.

Sometimes a club fits a player like a conker and its shell. Sunderland and Doig were meant for each other. The Mackems craved only the best footballers and in ‘Teddy’ they had acquired a masterpiece. Though records alone cannot narrate Doig’s wondrous performances on Wearside – contemporary match reports are peppered with terms like ‘brilliance’, ‘daring’ and ‘cat-like’ – they say much: four league titles won and over 400 top-flight games.

Collectively, Sunderland were known as The Team of All the Talents; Doig was popularly referred to as Prince of Goalkeepers. When the Talents won the league in 1894/95, the Prince was one of 10 Scots in the usual starting XI. Supporters loved Doig firstly for his otherworldly abilities, and secondly for his captivating personality. Notoriously hostile towards his own bald head, Doig wore a disguising cap.

Opponents would pull at it to rile him. If ever it should blow loose, it was said that the keeper would always chase hat over ball.

Circumstance – first that SFA policy and then Sunderland’s frequent refusal to release him for international duty – meant Doig never achieved the number of caps he should have done.

He was, notably, Scotland’s goalkeeper against England during the first Ibrox Disaster, in 1902. A match report noted that ‘It was a most unusual and impressive thing to see big stalwart men like Ned Doig looking on with tears in their eyes.’

When Doig’s time at Sunderland concluded after 14 years, Liverpool paid £150 to shift this northern star west. He was goalkeeper as they won promotion to Division One in 1904/05, but gradually lost his place to the England man Sam Hardy.

It was muttered that his performances had been affected by rheumatism. In 1908, Doig enjoyed his final game in red, now aged 41, before playing on for two years at St Helens Recreationals. At retirement, he had played more than 1,000 games of football.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Doig family remained in Liverpool, living still a few streets from Anfield. In early November 1919, Ned was taken ill. He died soon afterwards of Spanish Flu, less than a decade after his retirement from football. Death of Ted Doig, ran the Liverpool Echo headline, ‘Talents Goalkeeper and Splendid Fellow.’

Those who stroll by 18 Miriam Road on their way to matches now are passing the old home of a forgotten prince.