Insight: The pilgrimage to Lisbon to watch the Lions play

Dom Sweeney – self-made man and Celtic fan extraordinaire – is sitting behind a big desk in a big office in the headquarters of his property company in Glasgow. To his right is a table covered with photographs, testaments to a life fully lived. Most are of his sons and daughters, two of each, squirming in school uniforms or smiling under mortar boards: his own little dynasty.

Laid out on the desk in front of him are trophies of another kind: souvenirs from his trip to Lisbon to see his club win the European Cup in May, 1967. He has already shown me his passport, a pocket diary and a handful of hazy pictures from an Instamatic camera, the clearest of which shows four gallus teenagers on a dusty back road in France. But now Sweeney is beckoning me closer to look at a small white box. With due reverence, he opens it to reveal… what? Shreds of tobacco, perhaps, or wood shavings from the Cross? Neither. But this is as close to a Holy Relic as Sweeney is ever likely to possess: a few desiccated blades of grass from the Estádio Nacional; a piece of the very pitch where Tommy Gemmell and Stevie Chalmers’ goals secured their own immortality.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

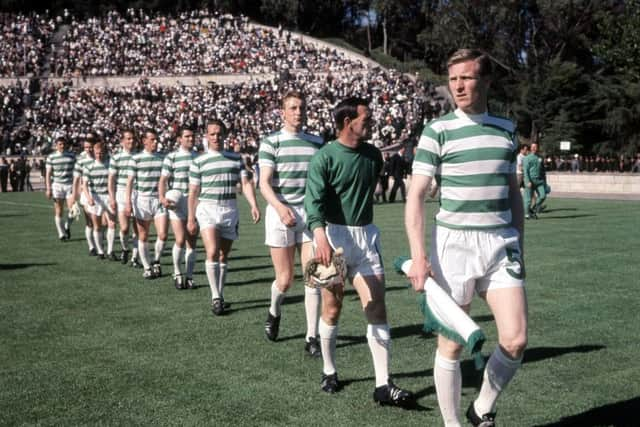

Hide AdSweeney – a dapper gent, with white, fly-away hair – was one of 10,000-plus fans who travelled to see 11 players from the still mean streets triumph over legends Inter Milan 50 years ago next month. From the Gallowgate, from the Gorbals, from Govanhill, from Garngad they came – hard-working labourers and Barrowland bovver boys alike – having scraped together enough money for the ticket and the journey, and precious little else. Some travelled by plane or train or in the “Celticade” led by Evening Times reporter John Quinn in his Hillman Imp. Others, including Sweeney, hitchhiked.

To those of us raised in the era of the replica strip, they look a stiff bunch, these men who refused to surrender their winter clothes to the threat of sunshine. But, off, off, off to the Continent seven years before Y Viva España heralded a British invasion, they were champions of the charter flight, pioneers of the package holiday. And their respectable facades masked an inner recklessness. For they went on to have the wildest of times. They ran jubilant on to the pitch, they partied in the streets, they spent all their escudos and threw themselves on the mercy of the British embassy. And they returned home with a panoply of stories, which they burnished and embellished and showed off like war medals for half a century.

Stories, Sweeney has a few. Aged just 17, and with £12 in his pocket, he and a friend thumbed lifts from Glasgow to Dover, took the ferry across the Channel, then walked the 20 miles from Calais to Boulogne, hooking up with two more pals along the way. At Boulogne, they caught up with the Celticade, inveigling their way into the back seats of cars. They made it to Lisbon in plenty of time, sleeping in a doorway the night before the game. And what a game it was. Sweeney recalls the surge of adrenaline as Gemmell knocked the ball into the back of the net for the equaliser, the chaos after the final whistle and the moment Billy McNeill lifted the trophy: a Greek god atop a stately amphitheatre.

But his best anecdotes, the ones he tells with greatest gusto, don’t involve the match at all. There’s the one about setting off from his Govanhill flat at 8pm, and making for a haulage company where, rumour had it, a truck driver called Archie would be willing to take them as far as London. “We arrived, our Celtic scarves wrapped round our necks, and we waited and waited,” Sweeney laughs. “Finally, Archie turned up. ‘These boys are wanting a lift to London,’ says one of the workers. Well, Archie took one look at what we were wearing and said: ‘That’ll be f***ing right.’ That was when we realised Archie was a Rangers fan.” Somehow, Sweeney and his friend made it out to the A74. But it took them many rides and 22 hours to reach the capital.

Then, there is the story of the impounded passport. After the game, Sweeney and his friends ran out of money so – along with hundreds of others – they pitched up at the embassy looking for a sub. It was mayhem. “There were Scots in sleeping bags all up the marble staircase and some guys frying sausages on a stove in the foyer,” he says. They were given £5 each, which – naturally – they spent on a trip to Estoril, the up-market resort where the team were staying. They tried to peek through the windows at the players, then lay on the beach where they all got burned. Sweeney had blisters all over his body. Out of cash again, they trooped back to the Embassy, where he promptly collapsed. Taken to the British Hospital, he was doused head-to-toe in Calamine lotion.

Finally, officials agreed to fund their journey home, but, wise to their spendthrift ways, they refused to give them the cash, insisting they turn up at the station the following morning. “This woman met us – I think it was 8am – handed over tickets and packed lunches and sent us on our way. That was us, through Portugal, Spain, France, England and back to Glasgow. I felt terrible, and we had to hand in our passports at Dover, but it was worth it.”

As the 50th anniversary approaches, and Celtic prepares for a week of celebrations, there are those who wish these stories would dry up now. They are tired of old-timers going on about how they sold their house to fund the trip, and the way the Lisbon Lions mythology has come to dominate Scottish footballing history. Feyenoord – perpetual underdogs to Ajax – beat Celtic in the European Cup three years later, and yet, in its stadium museum in Rotterdam, the victory merits only a fleeting mention. So why does 25 May, 1967 continue to wield such a powerful grip on the Glasgow psyche?

Sweeney has another story which may shed some light. It goes like this. Not all the turf he brought back from the Estádio Nacional is still in the little white box. A devotee of JFK – whose photograph once graced the walls of the Celtic boardroom – he swapped a few blades for a tiny bit of the grassy knoll brought back by an acquaintance from Dallas, Texas.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis exchange marked a literal and symbolic mingling of two seminal moments in the history of Irish Catholic identity. Seven years after Kennedy’s election helped validate Irish Catholics in the US, their counterparts in Glasgow were still struggling for recognition. Discrimination was rife; whole industries were out of bounds. The fans who travelled to Lisbon knew what it meant to be asked what school they attended. And that discrimination extended to football. “A Catholic could be the best goal scorer in the land, but they’d never play for Rangers,” says one fan. “It was hard to shake off a sense of injustice.”

You didn’t have to be Catholic to be involved with Celtic – Jock Stein was, famously, a Protestant – but the extent to which club and faith were intertwined could be seen by the splashes of green and white that brightened up churches in Lisbon on the morning of the match, which was also the Feast of Corpus Christi, and in the number of Glasgow priests who said an extra prayer for an incorruptible and keen-sighted referee.

Seeing the club – whose players lived in the same tenements in the same streets as their supporters – prove themselves in Europe was more than just an excuse for a party, it was a much-needed injection of self-confidence. Is it too fanciful to imagine it helped propel a generation on to success? Because, against all the odds, many Glasgow-based Irish Catholics born in the 60s or early 70s reached the tops of their professions. Some like Sweeney – aka Mr Artex – built up businesses from scratch; others went on to storm the Protestant citadels of finance, law and medicine.

Many cultural shifts contributed to this phenomenon. There was the disintegration of the old industries, the introduction of comprehensive education, and the chippy determination that comes from being continually put down. But Celtic’s European success is somewhere in the mix.

“When you talk about 1967, you are talking about a time when [Irish Catholics] didn’t feel accepted by mainstream Scotland, so this victory is not just a sporting victory, it’s a victory for a community, which rightly or wrongly felt themselves to be oppressed,” says historian Professor Sir Tom Devine. “The pride was incredible and it did represent a phase in emancipation. It wasn’t the only factor – the educational ones were much more potent – but in terms of signal events, the Lisbon Lions victory probably stands alongside the visit of Pope John Paul II in 1982.”

One family caught up in the swirl of social change were the Cowan brothers: Jimmy, 74, John, 69, and Gordon, 63, whose disparate lives are fused together by a passion for their team and the shared memory of one fine day in the Portuguese capital.

At his home near Queen’s Park, Gordon is sifting through a mound of keepsakes – tickets, programmes, newspaper cuttings – to find a photograph taken on the way to the game. It shows the brothers, their father, also Jimmy, and two family friends, under the awning of what was then known as Abbotsinch Airport. Gordon, 13 has a cheeky grin on his face, and a hold-all containing a whole cooked chicken at his feet. Jimmy Snr is wearing a tie and holding a placard for Sarsfield Supporters Club.

Jimmy Snr was – the brothers agree – a larger than life character full of drive and vision. He was the kind of man who, with the right education and opportunities, would have gone on to achieve great things; the kind of man who, on learning that Celtic had made it to the final, thought nothing of walking into a travel company and chartering a flight.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThough they must have recounted it 1,000 times, the brothers still sound awestruck by his daring. “Other people were booking individual flights through holiday companies, but he believed he could fill a plane so he raised and paid the £300 up front,” says Gordon.

“Remember, back then there were no mobile phones, no social media, so it was much more difficult to organise things. And many working class people had never been abroad. But our phone was ringing off the hook right up to the last minute, with people desperate to secure a place.”

Jimmy, a fireman, was born in the Protestant stronghold of Bridgeton Cross but brought up his own family in the Gorbals. By 1967, the family had moved to a tied house in Pollokshields, but Jimmy continued to serve as bus convener for Sarsfield Supporters Club (now renamed Jimmy Cowan Evergreen in his honour).

His plan, though well laid, was not without its flaws. To the Cowans, the European Cup final was just another away game, so it seemed reasonable to catch a 9.30am flight for a 5.30pm kick-off. With hindsight, however, they were cutting things a bit fine.

At the airport, events careened out of control. “At first the place was buzzing and everyone was buoyant,” says Gordon. “But it quickly became apparent there were delays. The guy my dad had been dealing with, a guy called Mr Bell, who looked like Leonard Rossiter, kept insisting everything would be OK, but our flight slipped further and further down the list.

“In the end tensions were running so high, reporters were sent out. My dad was quoted in The Citizen. ‘James Cowan, 56, flight controller,’ it [wrongly] called him. The article went on to describe the ‘tremendous roar of relief’ when the flight was finally called. Aye, especially from the travel agent who thought he was going to be lynched.”

Many people on board had never travelled by plane before. It is said some tried to prise open the windows so they could stick their scarves out; others had a whip-round for the pilot. By the time they touched down at Lisbon, however, it was already 5pm, and a full-blown rammy seemed inevitable.

The air stewardesses opened the doors, ushering in a blast of hot air, but the steps were still in the process of being wheeled over. “I remember this guy with short sleeves and sunglasses looking up at us with a mañana, mañana expression,” says Gordon. “ So Jimmy, John and a couple of others decided to take matters into their own hands. They jumped, or rather dreeped, out of the plane and on to the tarmac. People ask us: ‘ How come they didn’t break a leg or ankle?’ But they didn’t.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOnce the steps were locked in place, the other passengers followed, forcing their way past all barriers. “An officious security guard or policeman had shut the door to arrivals, but one guy shouted ‘stand back Big Man or ye’ll get malkied,’ and he must have realised there was no way he could keep everyone calm, so he opened it.” The fans pushed through – Jimmy Snr still keeping a close eye on Gordon – and raced to find cabs. “I don’t know if it was a nervous release of energy, but when we got into the taxi we were in stitches.”

By the time they reached the stadium, the first goal had already been scored. “There were travellers sitting on the grass outside; a woman said ‘1-0 to Inter’ and my heart just sank, because in those days the team had perfected this defensive system called ‘catenaccio’, and when they scored, you might as well go home.”

Thankfully, though, Celtic’s attacking style won the day and many a macho west of Scotland heart combusted. “My dad was crying and he turned round and gave me a hug,” says Gordon. “I don’t ever remember him doing that before.”

Fifty years on, much has changed for the Cowans. Jimmy Snr is long gone. But he lives on through his three sons who remember the important things: the way he always thought bigger than everyone else; the way he stood against sectarianism; the way he took time out in Lisbon to buy a charm (a tiny gold ship from the city’s Coat of Arms) for his wife’s bracelet. The day he died, in December, 1997, the whole family had been due to watch Celtic play Hearts at Parkhead. Shellshocked, Jimmy, John and Gordon went anyway; they didn’t know what else to do.

Their father would surely be proud of what they have made of their lives. Now retired, Jimmy Jnr spent more than 30 years working for the Inland Revenue, while Gordon forged a career in life assurance. As for John, he was one of the first Glasgow-based Irish Catholics to scale the heights of the finance industry. He joined Scottish Amicable – where he was given a bowler hat and a Triumph Herald car – and eventually became a director. Today, he is the chairman of three companies and owns a £3.5m flat in Mayfair.

When the brothers returned to Lisbon, along with John’s son Christopher, to see Celtic play Benfica in 2012, they did so as “nice middle-class boys who could afford to stay in hotels”. But they haven’t forgotten where they came from. “People look down on the fact you grew up in the Gorbals, but I have always been proud of it,” says John. “Living in such a diverse community, amongst Poles, Lithuanians, Italians and Jews, was an enriching experience.”

It is 11am on 11 March, 2017, the day of the Old Firm match at Celtic Park. Jimmy, John and Gordon are standing beneath Billy McNeill’s statue, talking about you know what. Behind them, gulls swoop theatrically over the metal gridwork of the Lisbon Lions stand and fans cluster round the floral tribute to Gemmell, whose funeral took place a few days earlier.

They are fading out, the men who took the club to glory. Ronnie Simpson, Bobby Murdoch, Jimmy Johnstone and Gemmell now play on Elysian Fields. McNeill has dementia. No-one knows if he remembers how it felt to raise the Cup before an adoring crowd.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe legacy they leave is mixed. Their success is a source of enduring joy, of course, and collateral against future losses. But some believe the relentless focus on their legend has been a burden on later players, who could never hope to rival their achievements, and on supporters, who can only ever experience the elation of ’67 vicariously through the moist-eyed reminiscences of their fathers.

Even were the club to triumph in Europe again, the pride would be less personal. Today’s star players, most of them brought in from abroad, do not – cannot – belong to the community in the way the Lisbon Lions did. The spirit of enterprise that sent Sweeney hitchhiking across a continent has been replaced by a shiny commercialism, evident in the 50th anniversary Hydro concert that sold out in 30 minutes.

The Cowan brothers do not have tickets for the gig. Instead, they plan to head back to Lisbon to bask, once more, in their shared experience. “Jimmy won’t remember,” John laughs, “but at the end of that game, I said: ‘You know, life will never ever get any better than this. They can stop the world now.’”

With that, he and his brothers set their faces against the wind and walk together – and ever-hopeful – into Paradise.