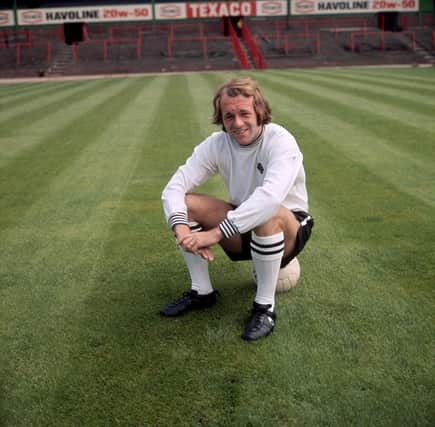

'I don't know how I scored it' - Archie Gemmill discusses Scotland's greatest goal, Derby, Nottingham Forest and his career

Now, bang up to the minute, there’s Wayne Rooney looking like a “suicidal bouncer”. Or a “Chechen guerrilla fighter”. Or a “57-year-old pub landlord in the dock for fiddling fruit machines”. These are all descriptions from press reports of Rooney in the courtroom, not as the accused but the supportive husband by his wife Coleen’s side in the “Wagatha Christie” libel trial.

Then, in 1970, it was Brian Clough in his pants. “Eh?” says Gemmill when I read out a version of events from when the Paisley Buddy, pocket battleship of the midfield and future Scotland immortal was persuaded to sign for Ol’ Bighead.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt says here, Archie, that Cloughie appeared in your kitchen in his Y-fronts having refused to take no for an answer – having the night before removed his shoes to plonk them on the fireside rug and announced he wasn’t leaving until you’d agreed to quit Preston North End and join his Rams revolution. Then in the morning he’s supposed to have whipped up some eggs for you both, possibly still only wearing his grundies, and that was the clincher.

“Well, almost true,” he laughs. “The discussions began in a hotel but Everton were interested in me too. We carried on talking at the house but when I said I couldn’t make up my mind and was off to bed Cloughie announced he was going to sleep in his car. My wife Betty wasn’t about to let him do that but we didn’t make him crash on the floor – he kipped in our spare room. It was Betty who made the breakfast and, yes, that was when I finally signed. ‘Come with us,’ he said, ‘and you’ll win the title.’ And he was right.”

Fifty years ago Clough and assistant Peter Taylor transformed unfashionable Derby into champions of England. Later they would transform unfashionable Nottingham Forest into champions and again Gemmill would be crucial. What a contrast between then and now. Both clubs have long since returned from whence they came – relative obscurity. But at least Forest have a chance of getting back to the big time with playoffs for the Premier League beginning today. Derby have just been relegated to the third tier.

“It’s sad what’s happened to them,” says Gemmill, “especially when you think of Coughie’s time, the team we had, him this mad genius who got everyone talking about Derby, absolutely convinced we were going to win the league, and making us believe it too.

“I went to bed that night at our house thinking: ‘Do I go with this man Clough who’s got the gift of the gab or should it be Everton where I could maybe have a nightmare?’ I obviously made the right decision because everything came from that. Cloughie said he and Peter would turn me into a Scotland player and a year later I won my first cap. I was so persuaded by him that I signed without knowing what I was getting [in wages]. Footballers don’t usually do that!”

Now 75, Gemmill still lives in Derby but, preferring to potter about in his garden, rarely visits Pride Park. It’s nothing personal, simply that as an old-school inside-forward he finds the modern game difficult to watch. What, viewing from afar, does he make of Rooney the manager? “At first I wasn’t sure at all. But everything considered he’s been no’ bad.” Those things that must be considered include the 21 points the club were penalised when they slumped into administration. “Wayne almost made up the deficit so fair play to him. The guy I blame is [owner] Mel Morris.”

Here’s another contrast between then and now, and it explains Gemmill’s disenchantment with the football he watches on TV: “Pass, pass, pass – but most of them are utterly pointless. Anyone can shuffle the ball across the park behind halfway – it doesn’t mean anything.”

To compare with politics, the contemporary midfielder is always fudging, ducking questions, hiding behind his Minister and stalling for the official inquiry – whereas Gemmill was the radical progressive who got things done. Watch, if it’s your thing, the players of today in his position race each other to amass the “most passes completed” no matter if many are mere flim-flam – then rev up YouTube for a typical piece of direct action from our man, such as his Match of the Day classic from 1977-78.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“One of my favourites,” he says, of his “Goal of the Season” for Forest against Arsenal on a City Ground mudheap when he plundered the ball just outside his own penalty box, passed out wide to Peter Withe and, instead of flipping open a garden chair to admire the rest of the counter-attack, scampered upfield as fast as his wee legs would carry him, acknowledged by an excitable David Coleman: “Gemmill’s arrived all the way from the back … Withe hasn’t seen him … he has now!”

Gemmill is Dark Blue royalty, scorer of course of Scotland’s greatest-ever goal, and was chosen for his tough, tigerish talents by Bobby Brown, Tommy Docherty, Willie Ormond, Ally MacLeod and Jock Stein. He was a product of that factory, formerly of world renown, which supplied English football with little big men who could look after the ball - and themselves.

His story began with hometown team St Mirren.

“I grew up in Candren Road, Ferguslie Park, my dad was a slater and mum a cleaner and as an only child, given what we had which wasn’t much, I was spoiled rotten.” Gemmill reached the undizzy height of 5ft 5ins – did anyone ever say to him regarding football: “Sorry, son, but you’re too wee”? “If they did I didn’t pay the slightest bit of attention,” he says.

His stature hadn’t put off Rangers who’d vied with St Mirren for his signature. “My dad, being my dad, decided: ‘You’re going to St Mirren. At Rangers maybe you wouldn’t be seen again. At Love Street you’ll have a chance.’”

He’s a quiz question, being the first substitute in a top-class Scottish match, against Clyde in the League Cup in 1966. “I came on for Jim Clunie, a Buddies man from birth to the day he passed away. Our centre-forward came from Iceland – Therolf Beck who we called ‘Tottie’ and who was looked after by my granny.”

Preston’s Scots helped him settle in English football. They included the Georges, Ross and Lyle, and Jim Forrest, banished from Rangers following the Scottish Cup humiliation at Berwick. There were, though, “a few problems with the managers, as happened often”. It was no help that Jimmy Milne then Bob Seith were fellow countrymen. Next in charge, Alan Ball, father of the World Cup winner, was the one to deliver the message: “Brian Clough’s been on the phone.”

Gemmill has had time to reflect on the whirlwind that blew through the East Midlands with two epicentres 15 miles apart. “At Forest I knew what to expect from Cloughie – his management was brilliantly simple. My job was to get the ball to Robbo [John Robertson]. Sometimes I think the modern-day managers talk too much and over-complicate the game. Obviously Cloughie talked a lot – he was a celebrity – but not to us about tactics. I can’t really remember any beyond that basic instruction. And as everyone knows, sometimes before matches he’d take us all for a pleasant walk, maybe even to a pub.”

The order had been the same at Derby for Gemmill; he was to supply their left-winger, Alan Hinton, nicknamed “Gladys” on account of his blond curls, white boots and lack of aggression. There’s another contrast between then and now – the name has fallen out of favour, for women and footballers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was an order, though, and Gemmill remembers having strips torn off him by Clough on the odd occasion he’d failed in his duty. Right now, if you never saw this guy play, you may be forming an impression of a mere water-carrier. This would be very wrong.

Go back to YouTube and seek out another terrific goal on the run for Derby in the topsy-turvy 4-4 Boxing Day, 1970 clash with Manchester United. It wasn’t Pride Park in those days but a snowbound Baseball Ground. Something else you don’t see very often in the era of the hairweave is the bald footballer. Two were prominent that day - Bobby Charlton and the Rams’ tall Welshman, Terry Hennessey - but no more so than the little Scotsman who would soon join them in thinning on top.

But oh that pitch - how did Derby ever win the title on what seemed like a permanent quagmire? “It was a bog,” laughs Gemmill. “A lot of parks were like that but maybe ours was the worst. Cloughie wouldn’t allow that to be an excuse, though. ‘There’s nothing wrong with it,’ he’d say, ‘and nothing wrong with the fellows in your team. Get out there and play.’ And I must say I loved the Baseball Ground: 42,000 most weeks, the crowd jam-packed and right on top of us, a great racket.”

Gemmill disputes the suggestion the gluepot in its challenging way improved the skills of Kevin Hector, Colin Todd, Roy McFarland plus the Scottish Johns, McGovern and O’Hare - “They were all smashing footballers.” But a key figure in the victorious ’71-’72 campaign was another Scot who was no longer at the Baseball but deserved the fullest mention in dispatches.

“Dave Mackay, who’d gone to Swindon Town [as player-manager], laid the foundations for that title and was with us in spirit. On the field and off it he was a fabulous person. He gave every single ounce when he played for Derby and if something went wrong in a game everyone always looked to Dave. In the season we won the league I don’t think I was the only guy who was still going: ‘What shall we do here, mate?’”

Derby would win it again three years later - with Mackay as boss. But the handover was far from smooth. After months of melodramatic tiffs with the club hierarchy, Clough and Taylor resigned in October ’73. The fans protested and campaigned for the duo’s reinstatement, as did Gemmill and the rest of the first-team squad. “We signed a petition and actually staged a sit-in. The directors didn’t want to come out of the boardroom and legend has it they had to relieve themselves in a champagne bucket.” Well, at least it wasn’t the league trophy.

“That was a hairy time. Dave stayed in the background and played it very cool. Then, on a Friday, it came to the crunch: were we going to play or not? If we’d said no we would have been in breach of contract. Dave made it plain the Cloughie era was over and if we didn’t accept that he’d have to move us on and that would happen very quickly. So we backed down.”

That wouldn’t be the end of Gemmill’s “problems with managers”. For Scotland Docherty didn’t pick him after a ’72 Home International defeat by England and the spell in the wilderness lasted three and a half years. “I was scunnered by that because I loved playing for Scotland. I missed the World Cup in West Germany and was so upset that I didn’t watch the tournament. I ended up with 43 caps, which was great and I cherished every one, but would love to have made it into the Hall of Fame.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

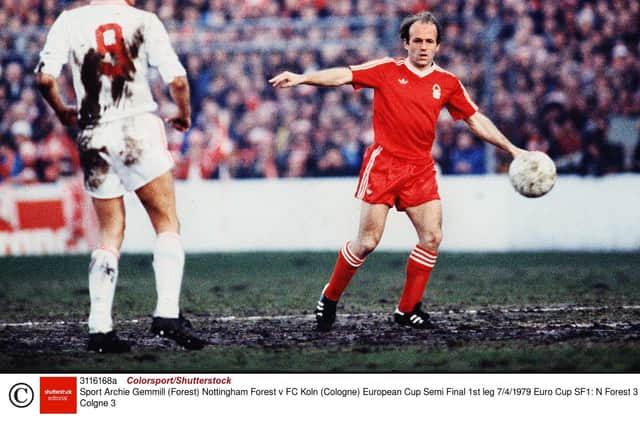

Hide AdThen at Forest, injured against Cologne in the semi-final en route to the first of the club’s two successive European Cup triumphs, he was dropped for the showdown against Malmo. “Cloughie said: ‘Get yourself fit and you’ll be playing.’ I did but he went with Ian Bowyer. Afterwards he wanted the medal I’d been given as one of subs. I said it was mine. He said if I didn’t hand it over I’d never play for him again. I chucked it across the floor and walked into the showers. It was an unfortunate end to our relationship but towards the end of his life we were able to make up with each other.”

Still, Archie Gemmill will always have Mendoza and so will we. The Argentina World Cup has been left until last today after his son Scot, who Gemmill wanted born north of the border in the hope he might one day play for Scotland which he did, lamented how for the old man the focus has always always been on the wonder goal to the extent those remarkable club achievements can be overlooked.

“Ach I don’t mind,” he says of the questions he’s been asked on and off since 1978. How did he score it? How did he feel scoring it? Did he wonder at that moment, 3-1 up against classy Holland, one more needed, what was happening at home? Did he know that Scotland, the entire country, was actually levitating? And again, how after that delirious dribble was he able to summon the composure for that perfectly gallus, quintessentially Scottish, chipped finish?

“I sometimes wish I had a better answer but the honest truth is I don’t know. You can call it a great goal, and lots of folk do but all I can say is I’m glad it brought some joy and still seems to be doing that even now, but I didn’t have a clue what I was doing out there!”

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.