Dundee United class of ’84 still feel Europe pain

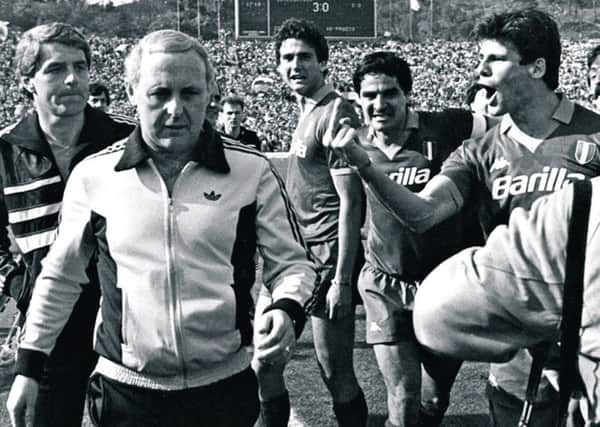

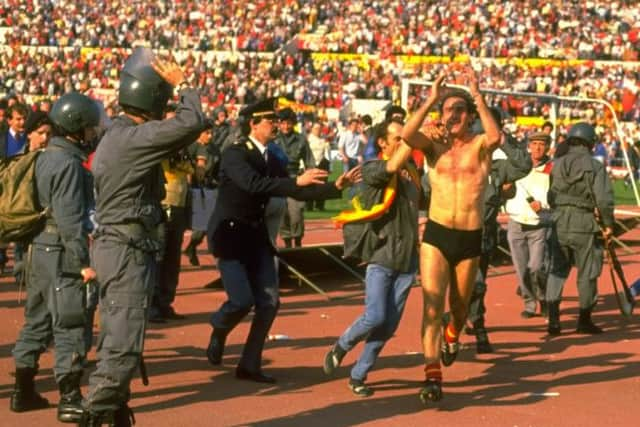

No sooner had the final whistle sounded at the Stadio Olimpico than some of the capacity crowd were on the pitch, Francesco Graziani – wearing only his black underpants – was swirling a shirt above his head and a group of his Roma team-mates, eyes burning with hatred, were sprinting for the touchline to seek out Jim McLean, the Dundee United manager.

Suddenly, the security guards that had been with United were nowhere to be seen and McLean found himself surrounded by a mob of threatening Italians, including Franco Tancredi, the Roma goalkeeper, and Agostino Di Bartolomei, their captain and playmaker. Visibly shaken by a barrage of verbal and physical abuse, McLean somehow withheld the response that would have caused a riot.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn a desperate attempt to protect him, John Gardiner, United’s substitute goalkeeper, and Walter Smith, their assistant manager, lodged themselves between McLean and his assailants as he headed for the dressing-room. “It was the first time I’d ever seen the manager upset,” says Gardiner. “They had obviously identified him as the target. Things got out of hand. They were swearing, spitting at him, punching him ... it was horrible to see. He was just covered in spit. I’d never seen anything like that towards a manager before and I’ve never seen it since. It was degrading.”

In the tunnel was a stairway that led to the dressing room. After McLean had squeezed through the gap, Gardiner and Smith plugged it. The two Scots took several blows to the ribs before responding with a few jabs of their own. A fracas ensued. “I wasn’t going to just stand there and let somebody whack me,” says Gardiner. “We threw our own back. It gave the manager a chance to get to the dressing room and clean himself up because it was disgusting what they had done to him, it really was. I don’t know if they would have hurt him, but the pressure they were putting him under was enormous. And, for the life of me, I don’t know why they picked him out.”

Maybe it was something to do with the 2-0 defeat his team had inflicted on them in the first leg of their European Cup semi-final tie in Dundee. With the final to be held in Roma’s own stadium a few weeks later, the prospect of missing out at the hands of a two-bit, cornershop club from the east of Scotland did not bear thinking about. McLean, more than anyone, was responsible for taking them to the brink of that indignity.

Roma were scared, and sometimes, when people are scared, they take leave of their senses. As the 30th anniversary of that semi-final approaches, all associated with United will reflect on it with a mixture of awe and anger. Awe that a side of United’s stature came so close to a showpiece final against Liverpool. Anger that they were treated so disgracefully by one of the powerhouses of European football.

This is a tale of intimidation, violence, bribery and, in the case of one Italian player, tragedy. “It wasn’t football,” says Paul Sturrock, a United striker at the time. “It was more than football.”

Had it only been about United’s exploits on the pitch, the story would have been compelling enough. That they, a provincial club with a 14-strong first-team squad, had won the league in 1983 was a miracle. That aggregate wins against Hamrun Spartans, Standard Liege and Rapid Vienna the following season should carry them into the last four of the world’s biggest club competition almost defied belief.

But here they were, locking horns with AS Roma, the Italian champions. The first leg, at Tannadice on 11 April 1984, was a culture shock to the visitors, a team sprinkled with household names, from Graziani and Bruno Conti to Falcao and Cerezo, all heroes of the 1982 World Cup. “They just didn’t like that it was a shitty wee stadium,” says Billy Kirkwood, the United midfielder. “They turned up and said, ‘is this the training ground?’”

United’s second-half performance was one of their greatest in Europe. Davie Dodds opened the scoring just after the interval. Derek Stark made it two with a thumping shot under Tancredi. According to Eamonn Bannon, a winger that night, it was United’s failure to score a third that cost them their place in the final. “We blew it in the first leg,” he says. “We should have beaten them by three or four, but we only made it two, and it gave them half a chance. We hammered them that night, hammered them.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the press conference afterwards, it was suggested that United must have been on something. “Well, whatever it was, we’ll be using it in the second leg,” was the gist of McLean’s flippant response, which turned out to be the catalyst for the controversy that followed.

The Italian media seized on his remark. Some said that McLean had called the Roma players “Italian bastards”. Others suggested that he had been cocky about his team’s prospects in the return. That nobody can quite put their finger on what McLean is supposed to have done wrong left many to conclude that it was an orchestrated campaign, constructed on the flimsiest of evidence, to make the second leg as uncomfortable as possible for United.

In his autobiography, Jousting with Giants, McLean absolved Nils Liedholm, the Roma manager, of all blame for the subsequent frenzy, but somebody, somewhere was responsible. Italian journalists, players and supporters turned on the Scottish underdogs with a vengeance. “Nobody wanted Dundee United to be in that final,” says Sturrock. “The crowd would have been halved. The TV rights and everything would have been affected. There was a lot of political stuff going on.”

In Italy, United fell victim to every trick in the book. The kick-off on April 25 was scheduled for 3.30 in the afternoon, when Rome was at its hottest. Their hotel was teeming with security men, whose dogs were allowed to bark 24 hours a day. The night before the match, motorbikes gathered outside to peep their horns and rev up their engines. When the Scottish players used the lift, they were greeted by a gun-toting policeman.

According to Gardiner, there were claims that United’s food, cooked by their own chef, had been deliberately contaminated. “They came out with some kind of soup, but the chef took it away, and the next thing we know, we are being told not to touch it because it has been tampered with. That’s how bad it was getting. We were fearful. It was an experience I’ll never forget.”

On matchday, the team bus was pelted with eggs and fruit as it arrived at the stadium. When the players emerged for the warm-up, oranges were thrown over the trackside mesh and on to their heads. “You can joke about it, but there were hundreds of them, thousands, and they were coming from a fair height,” says Sturrock. “Doddsy and I tried to break the ice by playing keepy-up with them, but it just incensed them even more.”

Plumes of smoke filled the air as a fevered crowd – bringing record gate receipts of more than half a million pounds – laid out the welcome mat. “God curse Dundee United” read one banner. “McLean F*** off” was the message on another. “The players were hyped up, the crowd were hyped up ... it really was over the top,” says Gardiner.

Goodness knows what the reaction would have been had Ralph Milne not slashed an early chance over the bar. It was to be a costly miss as two first-half goals by Roberto Pruzzi, and Di Bartolomei’s penalty, turned the tie on its head. For those in Scotland, who were watching on television, the only consolation was a technical hitch that interrupted the live feed. Early in the game, the broadcast briefly gave way to a snowy picture from which there emerged a snooker match between Jimmy White and Rex Harrison.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFew would dispute that, on the day, the better team won, but the manner in which United were intimidated almost certainly contributed to their uncharacteristically meek performance. In the TV commentary, Archie Macpherson described the atmosphere as “partisan and belligerent”. Sturrock says that he felt unsafe. Kirkwood suspects that United, who would later reach a UEFA Cup final in 1987, losing 2-1 to IFK Gothenburg, were just not ready for the experience. “For the players, the manager and everybody connected with the club to be 2-0 up against Roma in the semi-final of the European Cup ... it was mind-blowing,” he says. “Maybe it was just a step too far.”

Maybe, but the revelation, two years later, that Roma had tried to bribe the referee, Michel Vautrot, only compounded United’s sense of injustice. The Italian club were suspended from European football for a season, and their chairman, Dino Viola, was banned from official UEFA activities for four years.

The referee maintained that he never received the £50,000 – some claimed that the middleman did a runner with the money – but in 2011, Riccardo Viola, the chairman’s son, shed new light on the mystery. He told of a dinner on the eve of the match, when Vautrot was alleged to have informed them, in coded language, that the deal had been done.

During the game, United’s players had sensed nothing untoward. Vautrot seemed to be a homer, as many referees are in Europe, but none of his decisions was blatantly corrupt. He even disallowed a Roma goal. The theory is that, if there was a bribe, it must have been an insurance policy. “It was one of those games that, if we had been 3-0 or 4-0 up from the first leg, the Italians would still have won,” says Kirkwood. “Looking back, you could say there was no chance of us winning. They weren’t going to let us.”

For Sturrock, Kirkwood, Bannon and all those who took United almost to the summit of European football, only to be punched, spat on and accused of taking drugs, further evidence of foul play was the final insult. Last month, Sturrock wrote to Michel Platini, asking the president of UEFA to consider taking retrospective action. The Scot, who would go on to manage United, as well as a host of other clubs, has since received a reply in which he is assured that the governing body will look into it.

“If I’m asked, I would like the medals,” says Sturrock. “I think it would be appropriate if runners-up medals were given to all the players, and Platini himself came over to present them. I was lucky enough to finish up playing in a World Cup, which was probably the biggest thing in my career, but to play in a European Cup final, with Dundee United... that would have been incredible. I feel unjustly done by.”

Of all the tales to emerge from this sorry episode of European football history, perhaps the most disturbing was to come almost a decade later. On the tenth anniversary of the final against Liverpool, Di Bartolomei walked on to the balcony of his villa in San Marco di Castellabate and shot himself through the heart. In his suicide note, he referred to financial problems, a loan that had been refused, but the date of his death cannot have been a coincidence.

On the same day, ten years earlier, he had come up short against Liverpool, despite playing the game of his life. Desperate to lift the European Cup in the city of his birth, Roma’s captain won the man-of-the-match award, only to see his team denied by a goalkeeper whose eccentric mind games in the penalty shoot-out have been written into football folklore. “I can remember watching it,” says Gardiner. “When [Bruce] Grobbelaar did his shaky-legs routine, I’m sure everybody in Dundee was cheering. They [Roma] didn’t deserve to be there.”