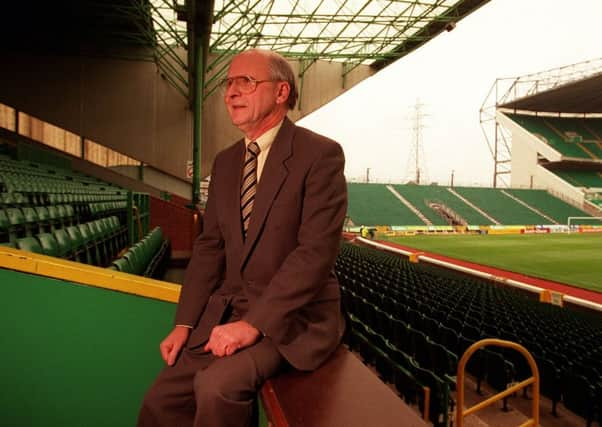

Andrew Smith: ‘McCann was brave, bold and bolshy’

The 20th anniversary reflections on Fergus McCann’s impact at Celtic have appeared somewhat one dimensional, dwelling, perhaps understandably, on his remarkable rebuilding of a football club. But as brave and bold as any commitment to bricks and mortar was the Scots-Canadian’s Bhoys Against Bigotry campaign.

At this point I must declare. I was editor of the club’s weekly publication, The Celtic View, for the first four years of McCann’s five-year tenure and so had involvement in the anti-sectarian initiative. It wasn’t, as some detractors claimed – the late Tommy Burns included – a “sop” to the business community, or an attempt to make Celtic more politically correct and “dilute their Irishness”. McCann sought to tackle the prejudices among the club’s support because he thought these were wrong, and that was the right thing to do. Many of us, a silent majority among those connected with the club, genuinely agreed with him. At times, McCann could be intransigent and infuriating and, to an unreconstructed leftie like me, alienating with his arch-capitalist, right-wing leanings. But I had nothing but pride in him, and admiration for him, in his daring to rail against what he called, with incredible courage, “Catholic bigots”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo challenge your audience – or customers, as he would have it – in such an unrepentant manner could have been considered commercial suicide. But he valued making a stand, and making a point about how there was an unpleasant religious undercurrent to the behaviour of some, above keeping punters sweet.

As might be imagined, the backlash that we felt at the View, through abusive phonecalls and letters, was intense. McCann had refused to indulge in whataboutery, but others did. They were raging that Celtic had taken the lead on this matter when Rangers’ problems were so much more widespread. Yet the aphorism-laden McCann had an answer to that: before you look out of the window, look in the mirror.

In asking supporters to refrain from singing songs that name-checked the IRA, old and new, he was accused of failing to understand the club’s roots. Yet, then as now, the counter-argument would run that there is more to Irish history than the war of independence or the Troubles. And, for a time in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the effect the campaign had was that – gasp – Celtic Park would regularly resound to songs about the football team.

The amusing volte-face among supporters and media on McCann, even between the tenth and 20th anniversaries of his Celtic takeover, has manoeuvered his reputation from Micawber to Messiah. In reality, he was neither, but rather a visionary the like of which Scottish football has rarely witnessed. That is enough, surely. Not least when the construction of a 60,000-seat stadium and his contempt for what he called, privately, David Murray’s “jam tomorrow” irresponsible governance explains why Celtic will not go bust and Rangers did. It was a blast to work with McCann because, as is too often overlooked, he had a highly caustic wit and a way with a one liner, and popular culture references.

“Principles, can’t afford them”, he would quote from Pygmalion, or mumble about “gold changin’ a man’s soul” from The Treasure of Sierra Madre after particularly fraught dealings with agents. “And all the stars that never were are parking cars and pumping gas”, was his Do You Know The Way To San Jose response to a journalist asking if he was worried about losing “stars” under freedom of contract. He also amused unwittingly, much of which related to his eccentricities and capacity for going from nought-to-narky in 0.1 seconds. I remember at a heads of department meeting, I made a complaint about the View losing the little cupboard in which we had been developing our own photographs, because it had been commandeered by the restaurant. McCann, till that point having seemed distant, suddenly jumped up and barked: “You guys playing darts! Why you playing darts!” No Fergus, I had to explain, I said I wanted the return of our dark room, not darts room.

In his first summer, we went to the Walfrid restaurant to do an interview reviewing the circumstances leading up to his takeover. As he sat down, he noticed that one of his “rebel” associates was also in for lunch, but had elected to remove his jacket before sitting down. “Look at that,” he squealed, “the man’s an ignoramus!” I still don’t know what etiquette rules were broken.

The subsequent interview – “eat faster, eat faster!” he said as I slurped my soup – resulted in both of us, and the magazine, being sued. The decision was taken to settle out of court. At that time the View was in the process of being brought back in-house, having been sold off to save costs in the dying days of the old regime. However, I still wasn’t a Celtic employee then and so McCann refused to pay my legal costs, which was more than half a year’s salary. As a goodwill gesture, the old publishers stepped in (keen to ensure they retained the publishing contract, it must be said).

Sentiment and business never were confused with McCann. When the View was to return in-house, it was decided there would be wage reviews. The intent was to pay the going rate. All staff were members of the NUJ, which the club would not recognise, but the union provided us with illustrations showing that our wages were 33 per cent lower than the national average. I was called in by the commercial director, expecting this to be righted, only to be told that there would be a smaller increase and that “you’ll just have to accept Celtic are poor payers in the sector”. Three years later I moved on for around a ten-hour reduction in my hours and 43 per cent increase in my salary.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere were aspects of the McCann regime that didn’t sit comfortably. With the help of his public relations guru who was effectively his consigliere, the club’s very history was rewritten. Out went the “Irish Catholic immigrants” element to describe the poor the club was formed to provide food tables for. Yet, in reality, Brother Walfrid’s driver for forming Celtic was not alleviating poverty but providing sustenance in a Catholic environment to prevent this discriminated community “taking the soup” elsewhere.

The whole charity fund/foundation element introduced in McCann’s time had more than a whiff of corporate plasticity about it.

Celtic’s charity operation was essentially a tax on supporters, who had to dip into their pockets to sustain it and then sit back as the club indulged in back-slapping. And the cloying talk about the club’s charitable origins – which only lasted ten years – started to be ramped up to an excessive degree in the McCann era.

The most egregious example of this occurred when the players became embroiled in a row over Champions League group stage bonuses in 1998. To make a point, and embarrass them for their “greed”, as he saw it, McCann decided to donate their £250,000 bonus pot to Yorkhill Sick Children’s Hospital. In itself, fine, but to generate maximum publicity, the club gathered children with leukemia to Celtic Park and had them pictured holding up one of those obligatory massive cheques. A tacky stunt.

He was never happier than when taking his lunchtime walk round the stadium as it took an ever-more impressive shape, or welcoming another financial big hitter on to the board. He was particularly excitable about the appointment of Quinn, a former deputy governor of the Bank of England. I interviewed the new man for the View and McCann asked that he see the piece before publication. With Quinn gushing about joining the club he had supported all his days, the article began “Lifelong Celtic fan Brian Quinn…” When it returned from McCann, this phrase had been scored out and above it he had scrawled “World respected businessman Brian Quinn...”

McCann’s rare feat was to straddle and serve both the football and business worlds, and yet, in the main, also make Celtic aspire to higher ideals of conduct. That is one monumental legacy.