Drug cheats will be a minority at Olympics

It hasn’t quite worked out like that, partly because with the International Olympic Committee still so heavily involved in running WADA, there is a conflict of interest. Being in the business of simultaneously promoting and policing sport is incompatible. As recent events have shown, it cannot work.

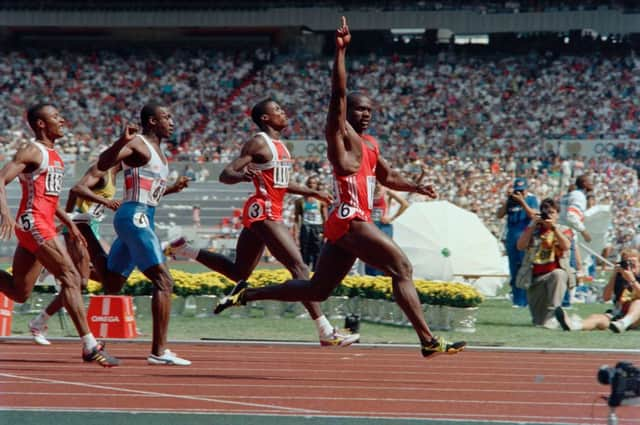

It seemed initially that it might. WADA was established by the IOC in 1999 in partnership with governments worldwide. It represented a first global and concerted effort to tackle drugs in sport 11 years after the biggest scandal ever to occur at an Olympic Games, when Ben Johnson tested positive after winning the 100 metres.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTen years after Johnson, it was the Festina scandal at the Tour de France that was the catalyst for WADA. It isn’t clear why, because the greatest investigation into drugs in sport was undertaken in Canada in the aftermath of the Johnson scandal.

It began in February 1989, lasted 11 months, called 122 witnesses and culiminated in a 600-page report culled from 1,400 pages of testimony. Charles Dubin, who led the inquiry, had old-fashioned ideas about sport and what it should be, but these were crushed by his own findings. Dubin spoke of sport’s “moral crisis”, despairing that some athletes took drugs “because of their inability to accept the limitations of their natural ability and because of a flawed system of values”.

Dubin reserved his most scathing comments not for the guilty athletes but for the governing bodies, including the IOC, whose failure to take the problem more seriously “contributed in large measure to the extensive use of drugs by athletes”.

A quarter of a century after Dubin, another Canadian lawyer, Richard McLaren, delivered yet more grim news for the anti-doping movement on the eve of the Rio Games. McLaren’s relatively brief investigation into Russian sport uncovered a sophisticated state-run doping programme. WADA called on the IOC to ban Russia from Rio but the IOC demurred, passing responsibility back to individual federations. Sir Craig Reedie, the WADA president, was critical of the decision, in particular the IOC’s decision to prevent Yulia Stepanova, pictured right, who helped expose the Russian operation, from running as an independent athlete in Rio. “WADA is very concerned by the message that this sends whistleblowers for the future,” said the agency’s director general, Oliver Niggli. But the IOC’s decision merely underlined where the power really lies – with the IOC. But of course – WADA is half-funded by the IOC; half of its foundation board are IOC representatives; half of its executive board is IOC. It is impossible not to see WADA as a semi-autonomous department of the IOC who can, if they say something the IOC doesn’t want to hear, be conveniently ignored.

It is no wonder that so many have lost faith in what they see at an Olympic Games. When it comes to sport, it used to be the hope that killed – now it’s the uncertainty.

But in all this uncertainty, there is an important point. It is this: that the failures of the IOC and anti-doping do not mean that all the athletes, or all the gold medal winners, are dopers.

There is not a grand conspiracy involving the 10,500 sportspeople who will compete in Rio. There will be cheats, but they will be in the minority. Only a cynic would believe otherwise.

In the wider world, cynicism seems to be on the rise and in sport it has grown out of the endless scandals and the failures of anti-doping. It spreads on social media, gathers momentum, and is then legitimised by “respected” commentators who should know better, until a sizeable community has declared its verdict on an athlete or team and abuses and bullies anyone who retains an open mind or dares offer an alternative view.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe have seen it in the case of Chris Froome, the now three-time Tour de France winner, but it can be directed at any world-class performer. It was this, and the understanding that it isn’t good enough for a journalist to form an opinion with so little information and next to no real insight, that led me to Jamaica after London 2012 to try to find out what I could about Usain Bolt, and the other world-class sprinters who have emerged from there, for my book, The Bolt Supremacy.

The uncertainty makes it difficult to know how to respond to everything that we will see in Rio, but cynicism is not the answer, because cynicism about sport and elite athletes is every bit as corrosive as doping itself.

There will be athletes who have doped in Rio, perhaps a large number, and some of them will win. But you can be pretty confident that there will be an even larger number who have not doped. And some of them will win.

Richard Moore is the author of The Dirtiest Race in History and The Bolt Supremacy.