Farewell to Ali, Cruyff and Palmer - sport's swashbucklers

In sport, flamboyance can be suppressed by innate modesty and the single-minded pursuit of victory but here too there were gigantic losses.

Can we find an attractive word which links Muhammad Ali, Arnold Palmer and Johan Cruyff? It’s easy. Stick “swashbuckling” next to their names in a search-engine and drooling testimonies result. Ali, for instance, was the “debonair, swashbuckling pugilist” while the great golfer and the great footballer were always swashing buckles throughout their careers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThink of their trademark moves and how these three lit up not just their own sports but all sport. With a drop of the shoulder and a 180-degree swivel, turning the ball with his right instep back inside his standing leg, Cruyff twisted the blood of the hapless swede Jan Olsson. This was the Cruyff Turn and immediately after witnessing the trick on TV an entire generation of young wannabe footballers attempted to master it.

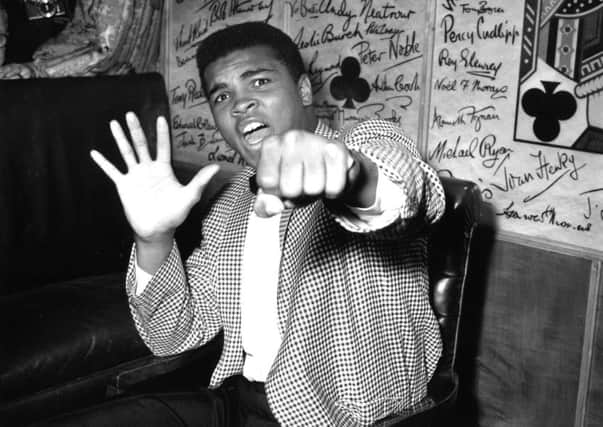

There was footage of the Ali Shuffle, viewed by a vast swooning audience, but less scope to mimic this swashbuckler without getting into trouble, unless you could plead playground provocation. The initial offence, though, would have to have been pretty bad to merit 11 fierce blows delivered in just three seconds. This was the punishment Ali meted out to British “hopeful” Brian London in 1966.

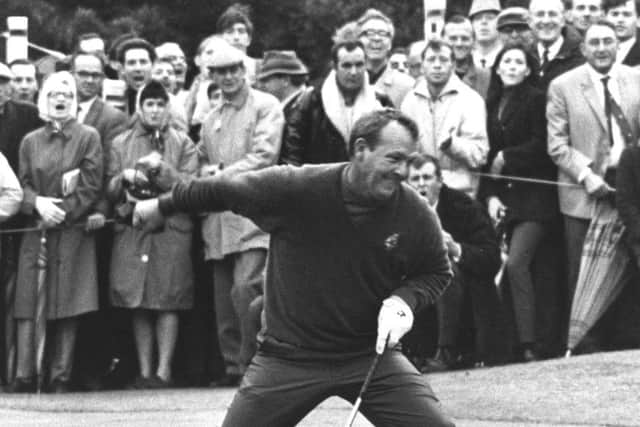

Palmer’s relationship with TV is interesting –indeed it was crucial to both the development of his sport and the success of early outside broadcasts. TV can claim that when it started taking a serious interest in showing sport in the late 1950s, it popularised golf – but the medium would never have been able to do this without the help of a man who removed the game from the smug country-club milieu like he would a ball from a troublesome lie and bestowed on it blue-collar appeal.

Troublesome lies were Palmer’s speciality, producing his signature shot. One of his glowing obituaries recalled the Los Angeles sportswriter Jim Murray seeing Palmer head into the rough where he was confronted by “a pile of leaves and twigs and I think there was a dead squirrel and a beer can in there, too”. This swashbuckler managed to extract his ball and return it to the fairway. “Trouble,” Palmer said, “is bad to get into but fun to get out of.”

The Cruyff Turn, the Ali Shuffle and the Palmer Charge – the latter’s perfectly-timed surge up the leaderboard to claim the prize, such as the birdie-birdie-birdie finish with which he won the 1960 Masters – connect through brilliance, although the trio of originators seemed to have little in common in their early lives.

Cruyff was the Amsterdam greengrocer’s son whose talent was spotted by Ajax at the age of ten, two years before his father died of a heart attack. His mother couldn’t run the shop on her own and became a cleaner at the stadium, re-marrying the groundsman. Cruyff’s maverick intelligence was at odds with traditional learning and he left school at 13, helping his stepfather paint the lines, driving the tractors.

Maybe there’s a distant echo of Palmer’s youth here for the latter, growing up in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, was plonked on a tractor by his hard-drinking golf-pro father at the age of six. “I had to stand up to turn the wheel. That’s one thing that made me strong,” he recalled. By seven he was earning five cents a time to hit the drives of Latrobe’s women members over a fearsome ditch.

And while Cruyff rejected school, or school rejected him, Ali, whose own father liked a drink, was rated as little more than a cretin by his local educational establishment in Louisville, Kentucky – 376th out of a school roll of 391 – while the US Army, initially at least, deemed him too dumb. These early assessments are right down there with Decca Records’ rejection of the Beatles, given the diamond-sharp wit and intellect which would later confirm Ali as TV Heaven’s most sought-after chat-show guest.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAll of our heroes were handsome and cool and while Ali and Cruyff possibly held the upper hand over Palmer aesthetically, golf in his era did not need another smooth swinger. A swishing, gung-ho, go-for-broke style was required and, as every enlistee to Arnie’s Army would testify, their man’s shots couldn’t have been more thrilling. Palmer and Ali were both accorded kingly status while Cruyff was the Prince of Holland. “I’m the king of the world!” proclaimed Ali while Palmer was nicknamed “the King”. But while Ali was boastful, and with very good reason, Palmer wore his crown lightly. “There is no king of golf,” he said. “Golf is the most democratic game on earth. It punishes and exalts us all with splendid equal opportunity.”

Maybe Palmer and Ali were more charismatic than Cruyff, the egocentric loner-genius of football. Ali advertised milk and Palmer marketed an iced tea-lemonade concoction, though, surely, Cruyff, in a less enlightened age, could have earned a lucrative gig promoting cigarettes for the suave way he smoked them. The arch-exponent of total football may have been haughty, but he still gave good quote, such as: “Treat the ball well, let it be your friend.”

All three swashbucklers were fearless modernisers for their sports. Ali was boxing’s first superstar and Palmer the first in golf while Cruyff was the first superstar of European football.

And all three were huge in Britain. We loved Ali coming over here and rendering our heavyweights horizontal and threatening to thump Michael Parkinson.

Our Open was listing as a top-grade international championship until Palmer finished runner-up at St Andrews in the 1960 event and won the next two.

Meanwhile, the Cruyff Turn, which left football open-mouthed at the 1974 World Cup, was given another outing three years later when the Dutch master – who should have been a ballet dancer, according to Rudolf Nureyev – dumbfounded England at Wembley.

What a shame he never turned out for Dumbarton at Boghead, but then even swashbucklers can’t have everything.