Aidan Smith: Ali changed the world (and invented rap)

Then I saw a still photograph of this beautiful man and realised I was wrong. Then I saw moving pictures and suddenly every other athlete was slow and cumbersome in comparison, not just every other boxer.

Then I heard him speak. In the 1960s everyone was funny, even if they weren’t a comedian. The Beatles were funny, Brian Clough was funny, the haughty grande dames of the Hollywood silver screen were funny and even Harold Wilson had his moments. But no one was funnier than Clay, or as he then became, Muhammad Ali. No one had changed their name before either, adding to his fabulous intrigue.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen you gain wisdom you realise that most pop bands, the vast bulk of actors and all politicians are actually quite dull. Ali never was, and he put every other sportsman to shame with his dazzling quickfire wit – then and especially right now.

In this PR-controlled age an athlete would pay a marketing whizz a lot of money to dream up a slogan the equal of “Floats like a butterfly, stings like a bee”. Ali minted that one, and the rest, by himself. Imagine him emerging today, with those tutors in media-training which sport employs so eager to work their bland alchemy, turning him into a “Take each fight as it comes” bore. You know he’d resist their attentions, and that he’d probably do it in verse.

Lucky Hugh McIlvanney, granted a two-hour audience with the man in 1974, just after he’d beaten George Foreman in the Rumble in the Jungle to reclaim the world heavyweight crown: “It was an amateur against a professional, a kid against a man,” declared Ali, awaiting lunch at his villa comprising two steaks and eight scrambled eggs. “I tell you somethin’, if he had got up I could have humiliated that boy. George has been actin’ up with fancy clothes and all that stuff with his dog, and misusin’ people, runnin’ the press around, talkin’ funny when he does talk. He used to be a nice fella’ but he’s changin’. You know how big it makes me to get the title back ten years after I won it from that other big bad bully [Sonny] Liston? Yet you can walk in on me here and talk to me, no sweat. Tomorrow I’ll be back in the ghetto pickin’ up black babies and drinkin’ soda at a corner-store… ”

Note the line “when he does talk”. A little jab at the inarticulacy of others. Some who didn’t care for boxing wondered how such a good-looking, intelligent man could be involved in such brutality. Many more only got interested in boxing when he emerged, fists and tongue moving so fast in a cartoon blur, and when he finally quit the ring they followed. He was a gift to boxing but he changed all sport – and, as a fearless and charismatic black man amid the civil rights convulsions of the 1960s, he changed the world, too.

Remember boxing when it didn’t involve Ali? In this country, for the armchair spectator at least, that was Harry Carpenter’s lunchtime round-up on Grandstand with the bigger bouts vying with rugby league for extended coverage on Sportsnight. I say bigger but these scraps would involve Brian London with his DA quiff or Billy “Golden Boy” Walker or Jack Bodell who Carpenter unfailingly fanfared as “the chicken farmer from Swadlincote”. They would be be matched with horizontal heavyweights, which might seem unkind, but this is how much Ali changed perceptions. He made all of these guys seem horizontal, apart from Henry Cooper who once managed to floor him – with a punch Ali generously described as being “so hard my ancestors in Africa felt it”. London, for instance, stumbled into a whirlwind – 11 fierce blows in three seconds. Think about it: all you’d manage to do in that time would be lift a coffee cup to your lips.

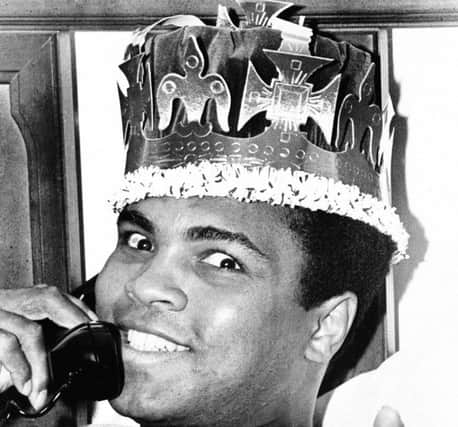

Did he invent rap? Think about that. “If you like to lose your money/Be a fool and bet on Sonny,” he chirruped. “Even Tarzan, the king of the jungle in black Africa, he’s white.” Then, bravely: “Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong.” The world hadn’t heard such jive talkin’ before. You can turn on a reality show today and see call-centre operatives behave in a brash and cocksure way – but in more deferential and restained times no one seemed to do this before Ali and certainly no one in boxing. Ringside pressmen – the white ones – were initially confused and irritated by the Louisville Lip. They’d been far more comfortable with the shy and retiring Joe Louis. There had always been braggadocio in boxing but suddenly there was this guy hollering: “I am the king of the world! I talk to God every day! I am the greatest!” And then Ali turned these bravura performances into chat-show gold.

Michael Parkinson’s best-ever guest – sorry Billy Connolly – rounds off the dream Saturday-night schedule in TV Heaven. From that delicious moment when we weren’t sure if he was going to slug his host, he became everyone’s Muhammad, but Ali was first and foremost a boxer and his passing will be felt most in paint-peeling gyms, among the broken-nose fraternity, and in a tiny flat in Leith.

Chatting to Ken Buchanan at his home a few years ago, the Scot was only too happy to recall his first encounter with our hero, despite having dined out on it ever since the unforgettable night backstage at Madison Square Garden. “It was me versus Donato Paduano and, further down the bill, Oscar Bonavena against some guy called Muhammad Ali – the only time a British boxer’s name has ever appeared before his,” smiled Buchanan. “Now he didn’t have a dressing-room. Angelo Dundee, his trainer, hurried over: ‘Can we share with you?’ Ali had a big entourage so I got a piece of chalk and drew a line on the floor. The place went silent. Ali said: ‘What you doin’, Ken?’ I said: ‘Just so we don’t get confused, Muhammad, this area is mine and that much smaller bit is yours.’ He just laughed.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Greatest” gets bandied around all the time now. Underwhelming men walk off with the title “Sports Personality”. Ali really was the greatest of the greatest and he had the charisma to power a chunk of Africa with enough left over for a certain London TV studio.