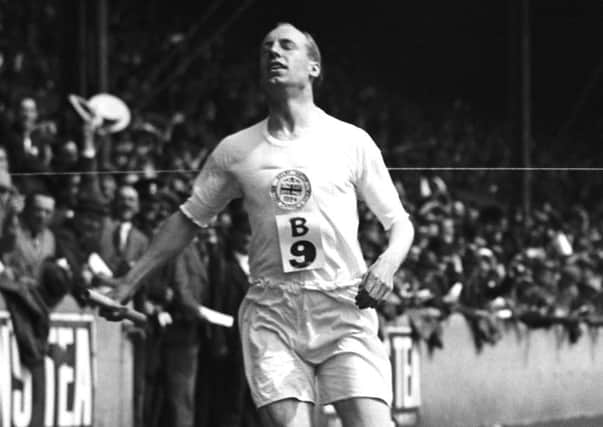

Alan Pattullo: Eric Liddell '“ the plain and simple Olympian

So it is handy to be sitting opposite Duncan Hamilton, author of a masterful account of Liddell’s life pre and – crucially – post the Scot’s 1924 Olympics success. Hamilton is confident he knows the answer; or at least he is as confident as anyone who has travelled so extensively and researched so forensically his latest biography’s subject can be.

“People tend to forget, he thought it should be a competition for individuals,” he says, stressing that Liddell would not be in favour of a medals table ranked on a country-by-country basis. “Because he knew from his own experiences and also from World War One, that nations go to war. And for some people the Olympics had become an extension of war.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is now often an equally off-putting carnival of self-promotion. “I think there is too much bling for him now,” adds Hamilton. “I don’t think Eric would go anywhere near the Olympics. I think he would still compete to a certain level but if he came back and saw what the Olympics were like now, I think he’d prefer to go back to when it was plain and simple.

“He would keep his counsel, congratulate everyone who won a medal – particularly a gold medal, because of the amount of sacrifice and sweat and blood you have to spill to compete at this level nowadays. But the commercialism, the doping certainly, he would not be in favour of that.”

Hamilton would be first to admit that he doesn’t speak for Liddell. But having travelled more than 20,000 miles, from the “spread of modern brick housing” that was once Powderhall stadium in Edinburgh to the internment camp at Weihsien (now Weifang) in China where Liddell breathed his last in 1945, aged just 43, he has been consumed by thoughts of him for nearly three years. It is therefore reasonable to assume Hamilton can provide a more than educated guess at where Liddell might stand if pressed on certain subjects.

The author can also confirm how feted Liddell still is in China. Even though the vest he wore when winning the 400 metres final at the Paris Olympics in 1924 featured a small Union flag, Liddell is regarded as China’s first Olympic gold medallist.

Hamilton notes, grimly, that a man born in China was fated to “always remain in it”. A small wooden cross, with Liddell’s name written across it in black boot polish, initially marked his burial spot in plot 59 of the camp’s graveyard.

Liddell’s commitment to the service of others meant he passed up numerous opportunities to leave as the situation in China, already bad, worsened following Pearl Harbor. His attitude was the antidote to what some regard as the shrieking self-regard of some Olympians today, and the hysterical flag-waving of some of those paid to report what is happening in Rio.

As Hamilton says, “it is not very many people who could honestly say the least significant thing they did in their life was win a gold medal. But that is how he interpreted it”.

On a visit to the University of Edinburgh, where Liddell’s gold medal from Paris is now on display, Hamilton is surprised to feel how “feathery light” it is. Liddell viewed his success as meaning more might come to hear the so-called “reverend with running shoes” – Liddell was ordained in 1932 – speak about his faith. “It widened his platform,” says Hamilton. This is what Liddell felt had been the real fruit of his success.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHamilton had his own platform last week back in the city where Liddell, who also played rugby for Scotland, honed his athletics skills under the watchful eye of innovative coach Tom McKerchar. The author was speaking at the Edinburgh Book Festival. It was a timely appearance since just a couple of days earlier Liddell’s memory was evoked following South Africa’s Wayde van Niekerk’s victory in the 400 metres final in Rio.

“Isn’t it ironic that the guy who won the 400 metres did it from the outside lane, like Eric, is a committed Christian, like Eric, and has an unconventional coach, again like Eric?” says Hamilton.

Van Niekerk also broke the world record, like Liddell. But it was Hamilton’s intention to cast light on Liddell’s life post-Paris, to take the story on from Chariots of Fire, where many, including those of us who drive past the Eric Liddell Centre in south Edinburgh almost every other day, might rather shamefully admit to having left this hero.

Hamilton, whose father was born near Bannockburn, was brought up in England on tales of Liddell. He watched the Oscar winning film of his “life” twice in the week of its release in 1981. “What I discovered doing the book is that the film is correct in so much that Eric refused to run the 100 metres because it was a Sunday, he ran the 400 metres and he won it, and all this occurred in Paris. And that was it!”

“But this does not spoil my enjoyment of the film,” he adds. “It is a fabulous script. It is one of those films where if you are surfing channels and you come to it 15 minutes in, you are there to the end.”

But the end of the film is not the end of Liddell’s life, some way from it. Hamilton is especially glad to have been able to uncover details, unrecorded in previous biographies and books about the Scot, of Liddell’s last race. Hamilton describes this performance as perhaps Liddell’s best, “and unquestionably his bravest”.

And yet he only finished second, to fellow internee Aubrey Grandon, whose widow Hamilton tracks down. By now suffering from the effects or what was posthumously diagnosed as a brain tumour, and despite, as one survivor notes, “no-one having much strength for athletics”, Liddell consented to competing at a Weihsien “sports day”. While the dying man narrowly lost, Liddell, in the eyes of his fellow prisoners who felt his kindness each and every day, was still a champion.

Hamilton admits to having been “slightly sceptical” when he approached this project, having already completed critically acclaimed studies of a trio of flawed geniuses – Brian Clough, George Best and Harold Larwood. After some initial basic research, he wondered if anyone could truly be as goodly as Liddell has been portrayed. He determined to apply some journalistic rigour to the task, which might have spooked Liddell’s three daughters, all of whom live in Canada. But no, they welcomed Hamilton’s intention to look at Liddell’s life from a “secular point of view”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHamilton’s account of his face-to-face meeting in Toronto with Maureen, the daughter Liddell never met, is especially affecting. He was used to seeing photographs of a baby with her mother and yet here she was, a woman in her early seventies. “There was a photo of her father in the corner of her flat,” he recalls. “Maureen has had to live all the way through with everyone else’s memories and recollections of her own father.

“If Maureen was sitting here she would say it caused her real problems. She used to say to her mother: ‘why did he leave us – was he really such a good man?’ It took a long time for her to be reconciled. That only happened in the last 30 years or so. I think when the film came out that helped.”

It’s clear Liddell was desperate to join his family in Canada, where they had re-located when it became clear their safely could no longer be guaranteed in China. He talked optimistically of his plans to work with the tribes of native North Americans and Canada’s First Nations people – again, his first instinct was to help others.

But someone who became a specialist at saying goodbye – at the boat dock, the railway station platform, even outside the school gates of the south east London boarding school where he was sent aged just six – was robbed of the opportunity to say a final farewell.

Florence, his wife, received old letters bundled together months after Liddell’s death, and one line stands out. It is a farewell of sorts since Liddell promises, despite everything and in a final affirmation of his faith, that “all will be well”.

But it is comforting to know that the equally saintly Florence, to whom Hamilton’s book is dedicated, lived long enough to hear Allan Wells’ simple proclamation on winning the 100 metres final at the Moscow Olympics in 1980.

“Did you win it for Harold Abrahams?” Wells is asked, with reference to the Cambridge runner who took advantage of Liddell’s refusal to compete on a Sabbath 56 years earlier.

“No,” the Scot replied. “For Eric Liddell.”