Scotland’s forgotten Christmas cholera outbreak

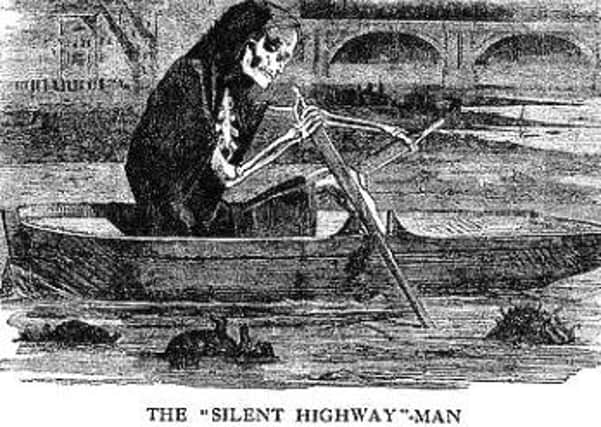

In Victorian Scotland, cholera was a frightening and little-understood killer. Only three years after the beginning of the worldwide pandemic, the bacterial disease - spread via infected water supplies - made its way from Russia and China to Britain, courtesy of a ship landing at the English port of Sunderland laden with infected persons from the Baltic states.

It wasn’t long before cases of infection were reported within Scotland, with the first reported cases recorded on 23 December 1831.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

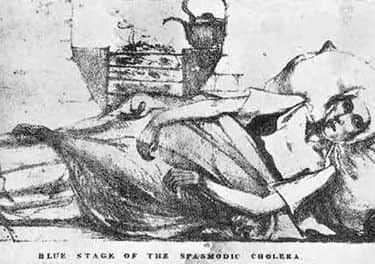

Hide AdThe effects of cholera were immediately noticeable: vomiting and severe diarrhoea would occur, with some victims noticing a bluish change in skin tone before death. While the disease spread to locations throughout Scotland including Edinburgh and Haddington, it was the Clydeside area of Glasgow that felt the vicious effects of infection most keenly.

Glasgow’s thriving port, busy with cargo ships from all reaches of the British Empire, and overcrowded living conditions in the tenements were mainly responsible for the spread of cholera throughout the west coast of Scotland’s communities.

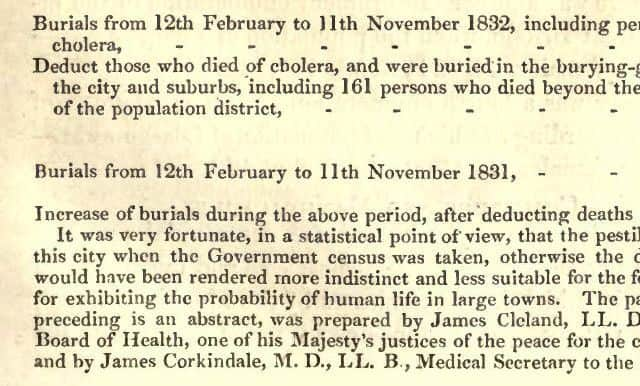

Over 3000 people died of cholera in Glasgow and approximately 450 in Paisley succumbed during the early 1830s, with the inability of doctors to treat the condition ramping up public fear of the disease. Such was the impact of the disease that cholera, along with fellow biological infection typhus, saw the death rate in Glasgow rise from little below 25 per 1000 in the late 1820s to approximately forty per thousand only twenty years later.

As the death rate regressed to that of 200 years previously, people began to fear a Burke and Hare-style conspiracy on the part of doctors to hospitalise those that were incurable, so that their bodies could be sold into the medical profession for dissection once they had died. As a result the Paisley Riots of 1832 were so violent that military forces were called in by the government to quash them.

Much of what we now know about cholera’s effects on Scotland is taken from The Visitor; a periodical which documented the cholera epidemic in 1832 which is now in the hands of the National Library of Scotland.

It shows that the disease spread quickly in industrial towns such as Glasgow, Belfast and Liverpool, and was accelerated by poor living conditions which lacked sanitation. Cholera Riots were also recorded in Paisley and Edinburgh as well as Glasgow.

In addition, the National Archives of Scotland also holds anecdotal evidence of the epidemic, including that of a letter by Alexander Todd of Paisley to his brother Matthew Todd on 24 April 1832. It tells of mass panic at the spread of the disease, with some of Alexander’s neighbours already having died of it. His letter also details mass burials of cholera victims, as well as the destructive effects of the riots.

Despite the largely futile attempts of the medical profession to control the disease, Dr. Thomas Latta of Edinburgh hit upon the idea of the saline solution, or intravenous drip, as a method of treating cholera patients in 1832. Latta correctly identified that a solution of salty liquids could substitute for the blood lost, but as he was unable to work out just how much was needed, treated patients still continued to die - albeit at a reduced rate than before.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSadly, cholera returned to Scotland in 1848 and 1853 in the same overcrowded and poorly-sanitised areas as before. It wasn’t until the creation of better quality housing and adequate sanitation facilities later in the century that the disease was finally tamed.