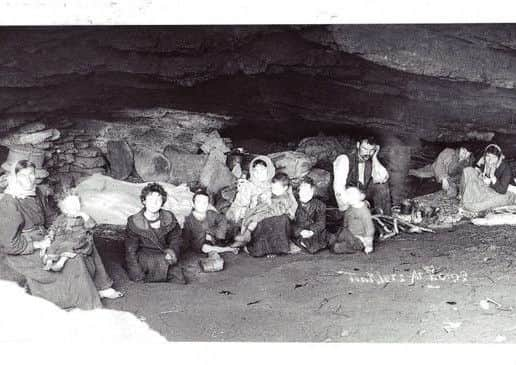

The forgotten cave-dwellers of Scotland’s far North

They were found resting in a cave, 24 men women and children, some naked and scarred, and all making the most of the dying embers of the fire. These were the cave dwellers of Wick, documented by Dr Arthur Mitchell, a physician who studied mental illness and who led several commissions into “lunacy” in 19th Century Scotland.

In August 1886, Dr Mitchell’s studies took him and a colleague to the “great cave” at the south side of Wick Bay at a time when caves were not uncommonly inhabited across the north and west of Scotland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe two reached the cave in falling light, around nine o’clock at night, and found the cave in a cliff with its mouth close to the sea, with high tides encroaching on the rugged habitation.

Dr Mitchell, in his account of the visit, said: “They received us civilly, perhaps with more than mere civility, after a judicious distribution of pence and tobacco. To our great relief, the dogs, which were numerous and vicious, seemed to understand that we were welcome.”

The spot at Wick became known locally as Tinker’s Cave, due to the folk living there being involved in the tin trade.

Dr Mitchell found the cave dwellers lying on “straw, grass and bracken” spread over the rocks and shingle, with each having “one or two dirty, ragged blankets.” Two of the beds were next to a peat fire, with more further back in the shelter of the cave.

His account added: “On the bed nearest the entrance lay a man and his wife, both absolutely naked, and two little children in the same state.

“On the next bed lay another couple, an infant, and one or two elder children. Then came a bed with a bundle of children, whom I did not count. A youngish man and his wife, not quite naked, and some children, occupied the fourth bed, while the fifth from the mouth of the cave was in possession of the remaining couple and two of their children, one of whom was on the spot of its birth.

“Far back in the cave-upstairs in the garret, as they facetiously called it-were three or four biggish boys, who were undressed, but had not lain down. One of them, moving about with a flickering light in his hand, contributed greatly to the weirdness of the scene.”

Dr Mitchell was told of another birth and also of the recent death of a child from typhus.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe physician added: The Procurator-Fiscal saw this dead child lying naked on a large flat stone. Its father lay beside it in the delirium of typhus, when death paid this visit to an abode with no door to knock at.”

On his visit, and according to his account, men and women - “naked to their waists” - gathered to speak to Dr Mitchell and his colleague - and showed “no sense of shame.”

A boy brought a candle from the garret and a woman tended the fire, lit her pipe - and then “proceeded to suckle her child,” he wrote.

The following day, Dr Mitchell returned to find 18 “inmates” eating an early supper of porridge and treacle, which he noted as “well-cooked and clean.”

Three fires warmed the cave, each surrounded by women and “ragged” children. Stones were used as tables and chairs at the cave, which Dr Mitchell found was occupied during both summer and winter, depsite there being no cover at the cave mouth, to protect from the “fierce” winds.

In his account, Dr Mitchell wrote: “I believe I am correct in saying that there is no parallel illustration of modern cave life in Scotland.”

He added: “The Tinkers of the Wick caves are a mixed breed. There is no Gipsy blood in them. Some of them claim a West Island origin. Others say they are true Caithness men, and others again look for their ancestors among the Southern Scotch. They were not strongly built, nor had they a look of vigorous bodily health. Their heads and faces were usually bad in form.

“Broken noses and scars were a common disfigurement, and a revelation at the same time of the brutality of their lives. One girl might have been painted for a rustic beauty of the Norse type, and there was a boy among them with an excellent head.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite his welcome reception to the cave, Dr Mitchell was unflinching in his conclusions. He noted them as illiterate and with no religious belief, and added: “These cave-dwellers of Wick were the offscourings of society, such as might be found in any town slum. Virtue and chastity exist feebly among them, and honour and truth more feebly still.”

Cave dwelling in Scotland formally came to an end in 1915 under the Defence of the Realm Act, possibly to keep coastlines free from fires during World War 1. However, research has found that 55 people were still listed as living in caves in the 1917 government census.