Iain McIntosh, the man who draws for Alexander McCall Smith

IF YOU’RE any good as a designer, you can make a mark on a city. It’s not always a big mark, and most times people won’t even realise it’s you who made it. But it must be satisfying, all the same, to be Iain McIntosh. His work is all over Edinburgh, but you’ve got to know where to look. The logo for The Traverse, the castle in the masthead of the Evening News, the labels and packaging for Scotland’s best-selling single malt and one of its premium beers. All the illustrations in The Scotsman for Alexander McCall Smith’s 44 Scotland Street series for more than a decade. All the covers and artwork for his Precious Ramotswe books.

The two men are friends, and have been since the early 1980s, when McIntosh was a freelance illustrator working in advertising and McCall Smith was teaching medical law at Edinburgh University. So when, in May, McCall Smith had an idea for yet another series, he met McIntosh for lunch to talk it over.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

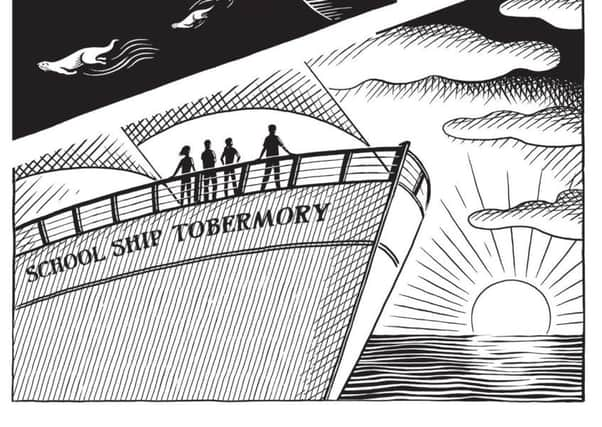

Hide AdSchool Ship Tobermory, published later this month, is the result. The first book in a new series aimed at children aged from eight to 12, it is based – rather typically for McCall Smith – on an idea that no other writer seems to have had before. It is set in a boarding school – nothing special about that – but a boarding school with a difference: one that floats. In fact, it’s a sail-powered training ship, based in Tobermory, and it travels round the world.

“Sandy was very enthusiastic about the idea when we met,” says McIntosh. “He hadn’t written a word of it at that time, but the scaffolding for the story was all in his head. He loves sailing – in the last ten years he’s got all his sailing qualifications – and he wanted to write something that would be like Patrick O’Brian but for children. And with a sailing ship school, you could go anywhere and have all kinds of adventures: you could fall off it into the sea, for example.” Or, he could have added, become a stowaway, or find out what a mysterious film crew that has turned up at Tobermory is really up to.

“It’s a great adventure story,” says McIntosh, “and it’s funny too. Sometimes, as an illustrator, when you read a text, half of your brain is thinking about what you’re going to draw. But here I got caught up in the text so much that I read it through right to the end. Sandy has put a lot of effort and enthusiasm into this and has honed it to perfection.”

The originality of the idea is matched in the artwork. At the end of each of the 12 chapters, McIntosh has drawn a page rather like you’d find in a graphic novel which, rather than taking the story forward, recaps what has just happened. “A bit like the poetry underneath Rupert the Bear?” I suggest. McIntosh beams. “That’s exactly it – except with drawings instead of poems.”

They’d got the idea from a series they had been toying around with about four years ago. They’d called it Tall Tales and the aim behind it was to tell a whole story in just four illustrated panels. “You know the stuff Sandy does, how it can go from very funny to quite serious and turn on a sixpence? Well, it was like that. One strip was about scientific ethics, another was about naming dogs. Sandy would do the words and I’d draw the pictures. It was quite easy for me to draw because Sandy had already roughed the strip out with stick figures. He’s good at thinking visually – remember, for example, how with the first No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency novel, he not only typeset it himself but designed the cover too? He knows and loves typefaces too, as well as being hugely interested in visual art. So he knows what he wants and is very easy to work with. It helps that we’ve both got a quirky sense of humour.”

An only child, McIntosh grew up in Motherwell, and was “good at art” for as long as he can remember. “Before I was five, I can remember sitting and drawing and listening to the radio. And that is exactly what I’m still doing now.

“You know how everyone is supposed to be able to remember what they were doing when President Kennedy was shot? With me, it’s as clear as anything. Lying on the floor, in front of the television, just after 7pm on a Friday and Michael Miles was presenting Take Your Pick! and there was a newsflash about Kennedy being shot in Dallas. I was copying the cover of the New Yorker my dad had brought back from a trip to America the previous month.”

McIntosh was nine. Within a year, he was going to Saturday morning classes at Glasgow School of Art, then when he got too old for them, to the evening classes there twice a week. There was no doubt that he’d go to art school – and possibly because he’d seen so much of Glasgow’s he went to Edinburgh’s.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlready he knew that he wanted to study illustration. It was something to do with the magic of reproducing images you’d already drawn. Because these were pre-photocopier days, that meant cranking out copies on the school Gestetner machine, and because its stencil duplicator technology was so primitive, clarity and legibility mattered more than anything.

Although the technology had shuffled forward a bit by the time he was a student at Edinburgh College of Art (where Harry More Gordon taught him illustration and Stuart Barrie taught him calligraphy), reproduction was still hit and miss: spend hours on a beautiful toned drawing in coloured pencil and copies might still come back blurred and distinctly underwhelming.

Far better, then, to stay with his own style, starting off with a black-on-white scraperboard but now on his Wacom graphics tablet computer, always aiming at clarity, often hinting at retro but still capable of covering the contemporary. Which is, he says, what he has done for decades, from punk fanzines in the 1970s, to advertising in the 1980s and 1990s, to the packaging and publishing work he mostly does today. His style, he says, hasn’t changed much, apart from a few nudges towards unfussiness – but then, if it’s all about clarity, why should it?

And for all McIntosh’s reliance on computers – for storing, layering and detailed cross-hatching – the basic techniques of his art have changed little. The day before we met, he was reading in Michael Pye’s The Edge Of The World about how in the eighth century Eadfrith of Lindisfarne had effectively come up with the first lightbox and the first lead pencil. He’d use lead to draw designs on the back of a page, hold it up to a strong light, and paint the page itself over them.

“And that,” he says, “is basically what I’m doing too. I’ll draw a sketch on paper, then scan it into the computer, fade it down a little bit, but go over it, improving the line as I go. I’ve got better technology, but really the process is pretty much the same.”

Which is true enough. Except when he was illustrating the Lindisfarne Gospels, Eadfrith didn’t have Radio 4 on in the background. And I bet it wasn’t half as much of a laugh.

• School Ship Tobermory by Alexander McCall Smith, illustrated by Iain McIntosh, is published by BC Books, £9.99