A blast from the past at Scotland’s forgotten dynamite factory

Eight men died at the British Dynamite Factory in February 1914 while handing gelatine in a mixing house on the vast industrial complex that was once embedded in the sand dunes on the Ardeer peninsula in North Ayrshire.

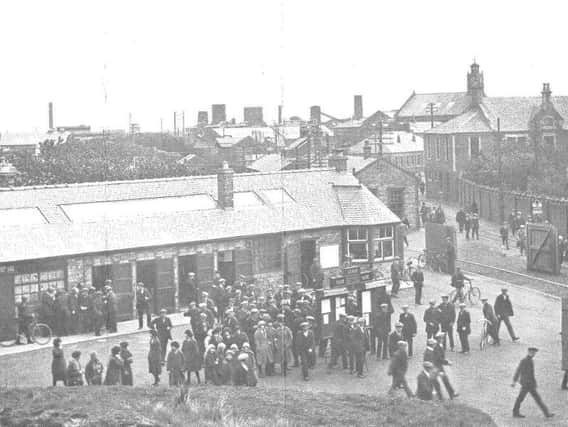

At least 6,000 lbs of explosives were in the building that disappeared that day with “heart rending scenes” reported as hundreds of women and children rushed to the gate for news of those who had been taken with it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne worker, Robert Moore, had just left the mixing house moments before the explosion.

“The bogey which I was holding was blown away, and I was thrown against the sand bank. I lay there for some time, not knowing what had happened, but as soon as I recovered ran round to see what had happened the others, but I could find no trace either of my comrades or of the house about where they had been working. Nothing but a big hole in the ground showed what had taken place,” Mr Moore recalled.

It was one in a series of explosions that mired operations set up by Swedish inventor and businessman Bernhard Nobel, the creator of a dynamite made from a form of nitroglycerine absorbed in a clay-like material, which could be handled relatively safely.

Despite the dangers of the job, the business was a major employer with up to 13,000 people working at the plant which functioned like a “mini town,” said Iain Hamlin, a conservationist who has taken an interest in Ardeer for many years.

“It had its own train station, its own bank and its own travel agent. It was a very important employer locally but it was also a very dangerous work.

"Lots of people got blown to bits, there was asbestos and some of those who works in the acid departments got their lungs damaged. There was also a condition suffered by those working with nitroglycerin, which relaxes and widens the arteries. People got used to it and when they went on holiday, for example, their bodies missed it. Some people ended up having heart attacks.”

Nobel took over the site in 1871, with the help of several Glasgow investors, with the dunes creating natural blast walls and the site suitably removed from the public.

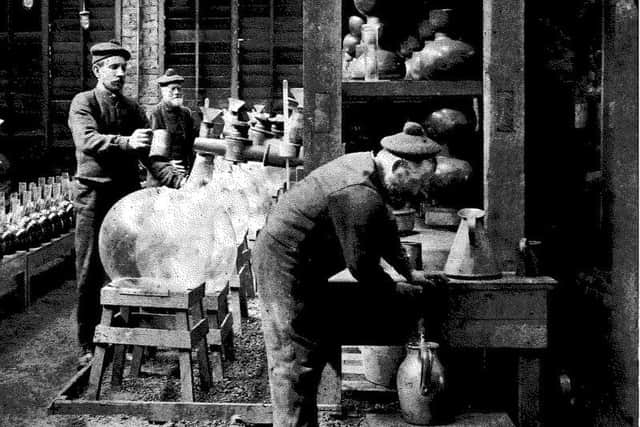

Export business expanded, particularly to the colonies, and by 1914 the plant was manufacturing an array of blasting explosives and chemicals, many which were supplied to the military.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdToday, abandoned industrial buildings can be found among the dunes, the rusted and twisted metal the last remaining traces of the mixing houses and the long huts where cartridges were filled by armies of women.

Mr Hamlin said: “There are still quite a few buildings there and you do get a sense of how it was.”

In one corner of Ardeer, you’ll find Chemring, which makes pyrotechnics and detonators, among other products, for the aerospace, security and defence

markets with the odd test explosion still heard today.

But the site has largely gone wild with the natural environment flourishing once again. The factory actually helped to bring wildlife onto the site, with woodland planted to screen the factory and fire pond since attracting new life. Biodiversity is king here, with more than 260 species of beetle recorded at Ardeer in recent years, plus a large number of wasps and solitary bees.

Mr Hamlin said: “The factory has gone but the wildlife has always been here,” he added.

Conservationists continue to object to both the industrial dredging of the sand dunes and plans the plans to connect Ardeer by bridge with a new waterfront development at Irvine. A holiday resort and new industrial site is also planned for the peninsula.