Art review: BP Portrait Award, Edinburgh

BP Portrait Award, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh

Rating: **

If there is one lesson to be learned from this year’s BP Portrait Award (and the lessons are few this year) it is that one should never trust a portrait painter, even in the family. While it may seem a welcome phenomenon that the vast majority of the 55 pictures in the 2015 exhibition of are of close friends, intimates and family members of the artists, the evidence is plain: they often favour misery over empathy and they will always show your weaknesses.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

Take Sophie Williams, born in 1993 and one must assume blissfully unaware of the complexities of the inner life beyond one’s twenties. She has portrayed her elderly grandparents in their kitchen. Once adventurous, she says, “Now their routines have become simplistic.”

She shows them clutching their spoons over their lunchtime soup in a double portrait entitled Just After Noon. While Williams’ work is skilled for such a young painter, and the painting is likeably constructed, the implied equation of the figures’ apparent physical weakness with some essential truth about their souls seems mistaken to me.

There really ought to be a law to prevent the young or even the middle-aged anywhere near the subject of old age. It is hard in this show to escape from the attempt. This is not so much the cruel ravages of time but the cruellest of clichés about the cruel ravages of time.

There are rheumy eyes, nostril hair and broken veins aplenty. José Luis Corella portrays the elderly Juanito in 1m x 1m of glorious Technicolor. The old man is in his vest with every cracked pore, wrinkle and age spot displayed up close. Raymond Huisman found his subject, Mr L, in an Amsterdam dementia ward. The subject’s face, lit by a nearby window, cranes towards the light but catches only blankness and confusion. These are figures without context and without hope, as though old age was a pit into which one always fell quickly and alone.

There are old folk in their pyjamas and a naked figure prone in a shower attended to tenderly by her child. One picture says it all: a smudgy monochrome of an old woman clutching a bottle, it is called Happy Melancholy.

There are few famous folk in this year’s batch. There’s Bob Geldof, his curly white hair like a secular halo, the losses he has suffered symbolised by the large blank space beside him. One yearns for a portrait of his recent happy marriage, or with his surviving children. Even sad people still laugh.

Portraiture was once a great art, and it still can be. But to do so it has to avoid the well-worn path and to acknowledge the tricky truth that appearances deceive as much as they ever reveal. Seriousness is not always a virtue. It can be an affectation.

Even the young folk in this year’s show are beset by bad moods and melancholy. There is more than one prone Ophelia, one female, and one male: the artist Ian Cumberland apparently afloat in his own bath. The men more often glower at us, through their thick beards and painstakingly acquired existentialism. Rich tattoos apparently symbolise inner restlessness or hidden depths. There are defiantly naked women, who seem somehow scorched or scalded in their nudity. Oh it is weary stuff and wearying to watch all that skill and talent, so carefully applied.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

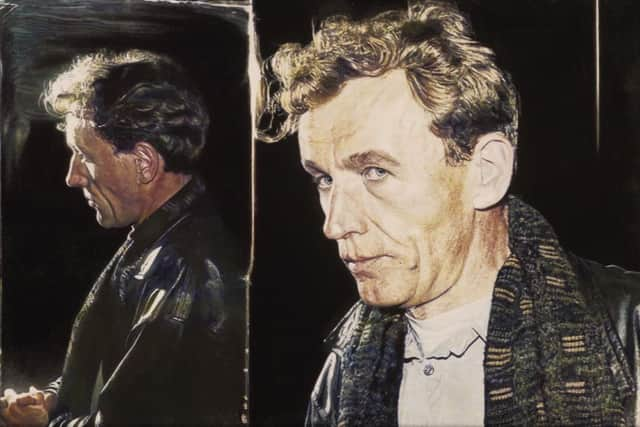

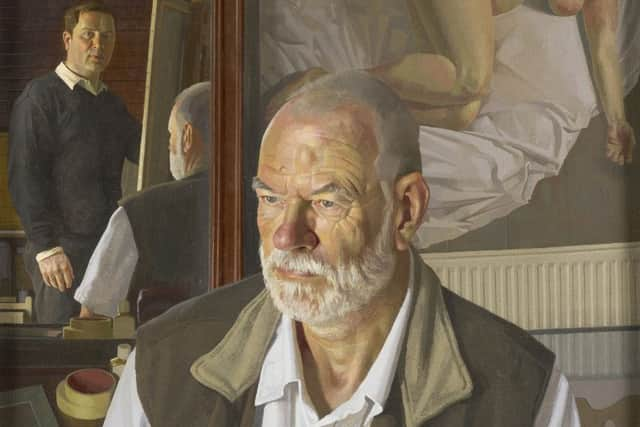

In its 36th year the portrait prize seems stuck, a familiar exercise. Whatever the merits or demerits of his work, the fact that Michael Gaskell, who this year presents a crystalline photorealist portrait, has been selected six times for the show and three years has been runner up, must suggest that the exhibition is short on fresh faces and innovative ideas. The organisers will point to the numbers, they received more than 2,700 online entries, but as the net grows wider its catch seems thinner and less varied.

There are some good things though: I loved Milan Ivanić’s picture The History Men of Dr Thomas Rokhrămer and Dr Kay Schiller deep in debate. Balding and bespectacled, they are also gloriously animated and alive.

• Until 28 February