An introduction to the art of the Glasgow Boys

They were fresh, real and somewhat rebellious and, by the end of the 19th century, the Glasgow Boys were the most significant group of artists working in Britain.

An informal collective of 20 artists, their most prominent members were William York Macgregor, Joseph Crawhall, George Henry, Edward Atkinson Hornel, Sir John Lavery and Arthur Melville.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey blew away old conventions of composition and storytelling in painting and forged a new path, with the artists heading outside with their easles to reconfigure representations of rural life and landscape.

Latterly, some of the group focussed on the pastimes of modern monied society, largely on the west coast of Scotland, while others immersed themselves in a potent mix of symbolism, folklore, texture and materials, including gold.

Anne Dulau, curator of the Huntarian Museum and Art Gallery, said the Glasgow Boys were caught up in a “current of change” that was sweeping the art world right across Europe in the late 19th century.

They were instrumental in pushing against the sentimental, chocolate box style from which sprung so many depictions of Scottish country life, from Sir David Wilkie’s Country Fair to Thomas McEwan’s Interior of a Peasant’s Cottage.

It was the overly sentimental content and the generally brownish tones created by varnish swept over the finished canvas that they particularly disliked and derided as “gluepot” paintings.

They headed outside with their easles to places such as Brig O Turk, Crail, Monaive and Cocksburnpath, where they sought to capture the everyday in its own right, from rural labourers to school children walking home - all under a moving palette of shade and light.

Ms Dulau said much of the Glasgow Boy’s work was in keeping with the Impressionist direction taken by painters such as Edouard Manet at the time.

She said: “By the late 19th century, European artists did not need to work to gether to share similar goals. This was a direct result of the new direction modern art was taking, and of it engagement with what French would call ‘l’air du temps’, or current trend.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn moving away from the “gluepot” style, she added: “They wanted to capture what was in front of their eyes, to work directly in the landscape, to look rather than copy, to feel rather than to analyse.

“Following in the footsteps of their idol, James McNeill Whistler, they believed in art for art’s sake.

“Painting had to be aesthetically pleasing and they weren’t interested in telling a story.

Ms Dulau said that the works of the Glasgow Boys did have its supporters of the day, despite the Impressionists’ work being widely derided by the art establishement.

She added: “When you look at what they were exhibiting in 1883, the Impressionists and their French and Dutch contemporaries had already broken the ice for the Glasgow Boys.

“There were collectors in Scotland who were travelling to exhibitions in London and in Parisand knew what was happening in the art world.

“When they saw the Glasgow Boy’s, they understood what was going on.”

SIX PIECES THAT DEFINED THE GLASGOW BOYS

Moniaive by James Paterson, 1885-6

Paterson lived in the Dumfriesshire village for many years. The balanced composition and muted colours were a tribute to Whistler, who was idolised by the Glasgow Boys for his rejection of established ideas about art.

A Hind’s Daughter, James Guthrie, 1883

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis was Guthrie’s first painting from Cockburnspath, where many of the Glasgow Boys relocated to in 1883 as they got to work experimenting with their new ideas. Here you can see a nod to another major influence, the French painter Jules Bastien-Lepage, a leader of the naturalist artistic style. Here in Guthrie’s work you can see a nod to theat movement, with the girl placed in low winter light against a high horizon. He has also worked in square bushstrokes, again a practice of Bastien-Lepage.

To Pasture’s New, James Guthrie, 1882-83

Here again Guthrie has recorded an everyday scene, but in a daring way. He created a sense of movement by cutting off one of the geese from the edge of the canvas. The scene is brought to life with an almost photographic composition, with the flat, agricultural lands represented in simple natural tones favoured by those seeking realism in their work.

The Tennis Party, 1885, John Lavery

The Glasgow Boys by now had reputation as landscape painters but some new directions and returned to well-off areas such as Helensburgh, Cathcart and pockets of Paisley to capture comfortable surburbanites at leisure. This work, which won medals in Paris and Munich, was painted at Cartbank and is considered in the vein of the Impressionists, with its large scale depiction of a social scene which caputure a wide spectrum of movement and light.

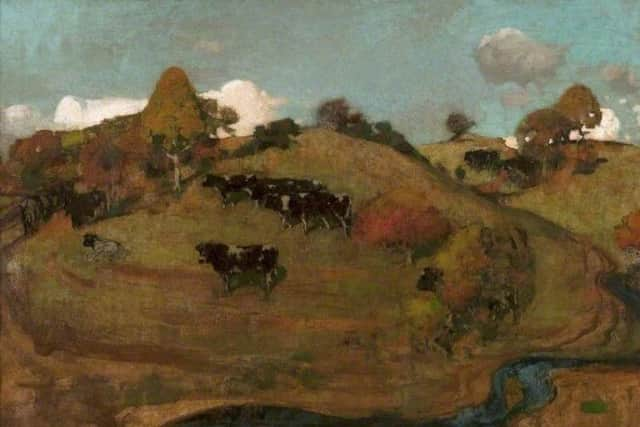

A Galloway Landscape, George Henry, 1889

Henry was to execute a major shift in the paintings of the Glasgow Boys’ work, with strong colours, pattern and design becoming increasingly crucial. Symbolism was taking over from more detailed and literal depiictions with nature represented through colour and texture. Here, you can see Henry’s blitz on horizon and perspective. An ordinary landscape is transformed and some have likened the effect to a Persian carpet.

The Druids - Bringing in the Mistletoe, 1890, George Henry and Edward Atkinson Hornel, 1890

Here you can see the use of symbolism in full flow. Folklore was a rich spring from which particualrly Henry and Hornel energised, This piece shows a group of Celtic priests and druids descending from a sacred oak grove. Mistletoe, highly revered by the druids for its magic and medicine, is entwined around the horns of the white cattle - an animal linked to regenerative cosmic power. The use of gold in the piece was also considered very daring, with only other artists experimenting with its potential being Gustav Klimt.