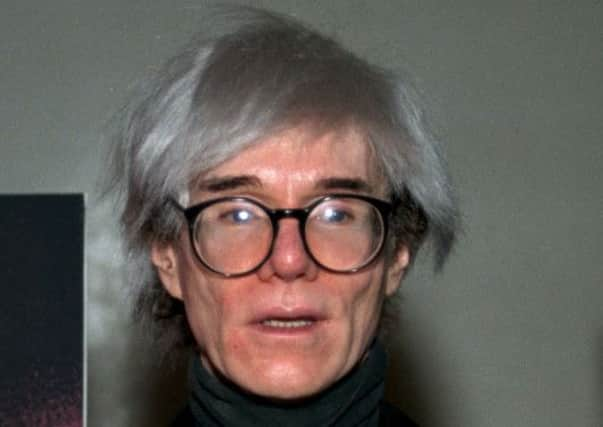

Unseen Andy Warhol works found on floppy disks

The previously unseen pieces, which date back to 1985, were found on ageing Commodore Amiga disks at the Andy Warhol Museum in his native city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania,

The disks had been stored in the institute’s archives for almost 30 years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe artworks were commissioned in 1985 by pioneering home computer company Commodore, which wanted Warhol to demonstrate the graphic capabilities of its new Amiga 1000, as it went head to head with Apple’s Macintosh series.

Although video footage exists of the artist creating the images – alongside the lead singer from the pop group Blondie Debbie Harry – at the launch of the Amiga 1000, the artworks themselves were thought to have been lost.

The artwork extracted from the disks included Warhol’s trademark Campbell’s soup tin illustration, a self-portrait and a recreation of Botticelli’s Venus Rising. It took a team of students and professionals three years to recover the artwork from its original format and the process has been captured on film.

A documentary film, called Trapped: Andy Warhol’s Amiga Experiments, which is based on their efforts will be shown at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Library Hall before going online.

The digital images were recovered by staff and students who are members of Carnegie Mellon University’s computer club. They worked in partnership with the Andy Warhol Museum.

The club was drafted in by self-confessed Andy Warhol fanatic and artist Cory Arcangel.

He noticed Warhol’s involvement in the Commodore Amiga launch on a YouTube video of the 1985 event and he contacted the museum in 2011 to get permission to search its collection.

Mr Arcangel said: “What’s amazing is that by looking at these images, we can see how quickly Warhol seemed to intuit the essence of what it meant to express oneself, in what then was a brand-new medium: the digital.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMagnetic imaging tools were used to copy the data from the disks so no damage was done to the originals.

Examination revealed several files that had titles such as “campbells.pic”, “flower.pic” and “marilyn1.pic” that were reminiscent of Warhol’s best-known works.

The recovery project ran into difficulties as the data was saved in an obscure format that modern Amiga emulators could not read.

Reverse engineering of the format helped to recover the images, many of which turned out to be signed electronic facsimiles of Warhol’s more famous creations. In total, 18 images were recovered, a dozen of which were signed by Warhol.

Andy Warhol Museum chief archivist Matt Wrbican said: “The Amiga hardware and Warhol’s experiments with it are one small portion of his extraordinary archives, nearly all of which was gifted to the museum from The Andy Warhol Foundation.

“In the images, we see a mature artist who had spent about 50 years developing a specific hand-to-eye co-ordination now suddenly grappling with the bizarre new sensation of a mouse in his palm held several inches from the screen.

“No doubt he resisted the urge to physically touch the screen. It had to be enormously frustrating, but it also marked a huge transformation in our culture: the dawn of the new era of affordable home computing.

“We can only wonder how he would explore and exploit the technologies that are so ubiquitous today.”

The museum holds an extensive permanent collection of art and archives.

Warhol, a leading figure in the pop art movement, died in New York in 1987 aged 58.