Quest for Lockerbie bombing truth takes a tentative step forward, but questions remain

That journey has seldom followed a straight line, and the latest development marks just the latest twist. It is a significant turn of events, but it raises more questions than answers – not least surrounding the conviction of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi – and coming so close to the 34th anniversary of the atrocity, provides a painful reminder the long wait for the truth is not yet over.

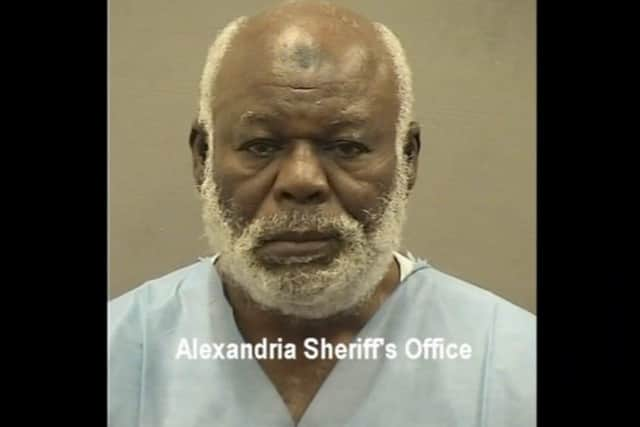

The US justice department confirmed on Sunday that Abu Agila Mohammad Mas'ud Kheir Al-Marimi, a former Libyan intelligence official, had been taken into US custody, nearly two years after the-then US attorney general, William Barr, unveiled criminal charges against him, which alleged that he built the bomb that that was placed aboard Pan Am Flight 103.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe circumstances which led to Ma’sud’s extradition from Libya are unclear, and will doubtless be subject to legal challenges, but he was set to appear on Monday evening in the US District Court of Columbia in Washington to face two criminal counts related to the 1988 atrocity.

All 243 passengers and 16 crew on board the Boeing 747 were killed as it flew over Scotland en-route from London to New York. A further 11 people on the ground in Lockerbie also lost their lives.

Mas’ud is the third Libyan national to be prosecuted in connection with the attack. In November 1991, al-Megrahi and another man, Lamen Khalifa Fhimah, were charged. They stood trial nine years later at Camp Zeist, a former US Air Force base in the Netherlands. Al-Megrahi received a life sentence, while Fhimah was acquitted.

Al-Megrahi, who always denied any involvement in the bombing, was freed by the Scottish Government in 2009 on compassionate grounds after being diagnosed with cancer. He launched two appeals against his 27-year sentence. One was unsuccessful and the other was abandoned. He died in 2012.

That same year, US authorities claim, Mas’ud, then imprisoned in Libya, confessed to his role in the bombing during an interrogation by authorities in Tripoli. The FBI only became aware of the alleged confession five years ago.

The US justice department claims he served as one of the most senior bomb makers under the regime of the late Libyan dictator, Muammar Gaddafi, but it is unclear at this stage what other evidence it has collated alongside the alleged confession from a decade ago.

In any case, the US believes Mas’ud worked with al-Megrahi and Fhimah as a co-conspirator. It was he, they say, who built the bomb, with the other two men placing it inside a Samsonite suitcase that was planted on a feeder flight and from there on to Pan Am flight 103.

For the families of those who were killed, the case against Mas’ud is a chance to find closure, but it is not without its own difficulties. Dr Jim Swire, who lost his daughter, Flora, 23, in the atrocity, welcomed the prospect of a new criminal case allowing all the evidence to be re-examined, while pointing out that he does not believe Mas’ud or al-Megrahi were involved in the bombing. But he stressed he and the other British relatives were seeking the truth, and not “a fabrication that might seem to be replacing the truth”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo that end, the prospect of Mas’ud standing trial in the US leaves many uneasy. Dr Swire referred to statements made by former South African president Nelson Mandela at a meeting of world leaders in 1997, when he said no one country should act as complainant, prosecutor and judge.

"I think it should not take place in America,” Dr Swire reasoned. “I think now, in view of what we now know about how Scotland handled the case, it should not take place in Scotland.

"The obvious way forward it seems to me is to resort to the United Nations and invite them to provide a court with appropriate facilities to try this man and hopefully to review all the evidence that was used against the unfortunate Megrahi."

It may be Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain KC has an opinion on whether Scotland has a greater claim to jurisdiction, given the crime took place over Scottish soil, but so far, she has only said officials in Scotland and the US will continue to investigate the case. Both she and the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS) stressed the “sole aim” was “bringing those who acted along with al-Megrahi to justice”.

But in light of Mas’ud’s impending trial, that insistence that al-Megrahi remains guilty has also sparked questions. Lawyer Aamer Anwar, who represented al-Megrahi and his family, questioned how both men could be held responsible for the attack, and described it as “another piece in the jigsaw of lies, built on the back of the Libyan people, the victims of Lockerbie and the incarceration of an innocent man”.

Mr Anwar, who intends to reflect on how the Mas’ud case impacts on any future miscarriage of justice appeal for al-Megrahi, said: “You now have the ridiculous situation of the United States, that prosecuted the case alongside the UK Government, alongside the Scottish authorities, against Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, saying 34 years later that, actually, no, it was a man called Mas’ud.”

There have long been doubts over the true perpetrator of Lockerbie, with many of al-Megrahi’s supporters of the view his conviction was a cover-up designed to protect the real protagonists. Those doubts may not be allayed once Mas’ud is in the dock. It all marks another tentative step forward in the quest for justice, but that journey remains far from straightforward.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.