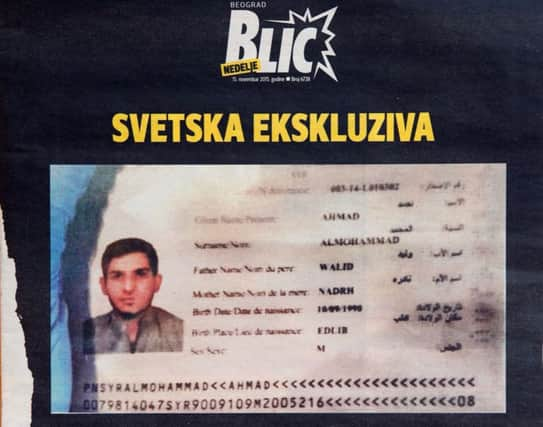

Paris attacks: Was terrorist’s Syrian passport fake?

The passport was found beside one of the suicide bombers at the national stadium. However, it was still not clear whether it is real or a fake, or whether it belonged to the bomber.

Greek officials said it had been used to enter Greece on 3 October through Leros, one of the eastern Aegean islands that refugees have used as a gateway to the European Union.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSerbian police said the passport was used at its border entry with Macedonia four days later, and Croatian police said the document was checked at a refugee centre the day after that.

The migrant corridor is known for its lax controls and the ease with which transit documents can be obtained.

Police in these countries said yesterday the owner was allowed to proceed because he passed what was essentially the only test in place – he had no international arrest warrant against him.

However, German defence minister Ursula von der Leyen downplayed claims terrorists were entering Europe as refugees.

She said: “Terrorism is so well organised that it doesn’t have to risk the arduous refugee routes, and life-threatening crossings at sea.”

Trafficking in fake Syrian passports has increased as hundreds of thousands of people fleeng war and poverty try to get refugee status. Most of those who enter countries on the so-called Balkan corridor for migrants – Greece, Macedonia, Serbia and Croatia –are registered with authorities.

Their data are checked against Interpol records, and their fingerprints and photos are taken. But many people tell officials they’ve lost their identity papers, and they can give false names and other information, including their country of origin.