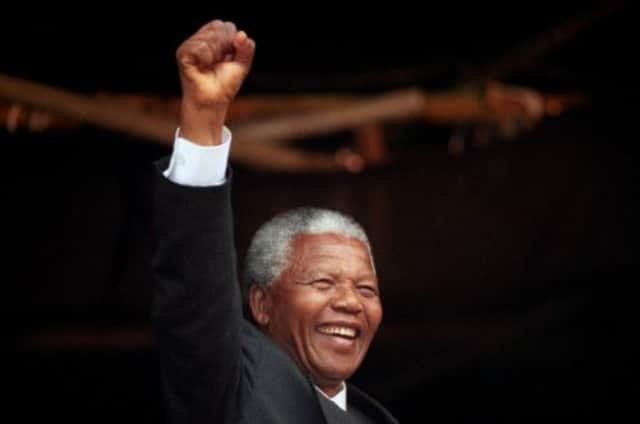

Nelson Mandela: Life of the leader

From his birth on 18 July 1918 in the village of Mvezo in the Transkei in the Eastern Cape province, Rolihlahla Dalibhunga Mandela was surrounded by influential members of the royal house of the Thembu people.

His father, a member of the Madiba clan, was an adviser to the royal house and on his death his nine-year-old son became the ward of the king of the Thembu people, Jongintaba Dalindyebo at the Great Place in Mqhekezweni.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was in this environment that Mandela heard the elders talk of their ancestors’ tales of valour in the wars of resistance and determined to join in the fight for freedom. Those who knew him as young man said Mandela always carried himself with the bearing of one who was born to lead.

Ahmed Kathrada, a former cellmate and long-time friend, recently recalled: “He was born into a royal house and there was always that sense about him of someone who knew the meaning of leadership.”

Mandela was sent to a Methodist school where he was given the name Nelson, in line with the custom of giving all children “Christian” names.

In 1939, he won a place at Fort Hare University, then a burgeoning centre of African nationalism.

He was expelled for joining in a student protest and eventually completed his BA through the University of South Africa.

In 1943, he joined the African National Congress (ANC), the organisation he would lead into government decades later.

After training as a lawyer, he rose through the ranks of the ANC, becoming embroiled in high-profile battles leading to him being arrested on numerous occasions.

In 1944, he married his first wife, Evelyn Mase. The couple divorced in 1956 and he married social worker Winnie Madikizela in 1958.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1956, he had been charged with high treason, but the charges were dropped after a four-year trial. He went underground and was dubbed “The Black Pimpernel” due to his skill in evading the police.

Following the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre in the Transvaal when police shot dead 69 protesters, Mandela, as commander-in-chief of the ANC’s armed wing, secretly left the country to raise money and undergo military training in Algeria, Morocco and Ethiopia.

Two years later, he was arrested, convicted of incitement and leaving the country without a passport, and sentenced to five years in prison.

But it was in 1964 that he really attracted the ire of the white authorities. Charged with sabotage, he was sentenced to life.

He had been facing the death penalty and his “Speech from the Dock” at the Rivonia trial on 20 April 1964 is regarded as one of the greatest of all time.

“I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination.

“I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities.

“It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve.

“But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was sent to Robben Island prison, off the coast of Cape Town, where he was subjected to a regime of hard labour. But it did not break his spirit and he was able to obtain sporadic news of the political struggle from people working on behalf of the ANC.

Mr Mandela, who had been a keen boxer in his youth, realised that his warders were keen rugby fans and learned everything he could about the sport and used this knowledge on his release as one method of unifying blacks and whites.

In February 1990, South African president FW de Klerk lifted the ban on the ANC. On 11 February, after 27 years in prison, including 18 on Robben Island, Mr Mandela walked free from Victor Vester Prison where he had been transferred.

In 1991, Mr Mandela became the first black president of South Africa. Accolades followed and many politicians, such as prime minister Margaret Thatcher who had branded the ANC a terrorist organisation, clamoured to meet him.

At the 1995 Rugby World Cup, Mr Mandela strode on the pitch wearing the green jersey of the largely white team with its iconic springbok emblem. It was a political move aimed at reassuring white fans that they were to be part of the nation’s future.

The photograph of him handing the Rugby World Cup to Springboks captain Francois Pienaar is regarded as one of the unifying moments in the new South Africa.

In July 1996, Mr Mandela met the Queen at Buckingham Palace, where a state banquet was held in his honour.

In 1999, he stepped down as president but continued to travel the world meeting world leaders and campaigning.

Family at loggerheads over legacy

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNelson Mandela’s death has left relatives continuing what has become an unedifying feud over his fortune and family.

Chief Mandla, Mandela’s eldest grandson, has had the bodies of three of Mandela’s deceased children moved from the family plot in Qunu village, where Mr Mandela spent his boyhood, to Mvezo, where he is building a cultural centre and backpackers’ lodge to attract tourists to the area.

At least 15 family members then took Mandla to court earlier this year to exhume the bodies and return them to Qunu in a case likened to a soap opera by the South African media.

In a separate dispute over Mandela’s legacy, his daughters Makaziwe and Zenani went to court in July in a bid to oust three of his aides from Mandela’s companies, said to be worth millions of dollars.

Among the aides were lawyer George Bizos, 84, and Tokyo Sexwale, 60, a fellow prisoner on Robben Island. They have, it was claimed by the daughters, “hijacked” a family trust intended for them.

WHAT HE SAID

“During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to see realised. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die”

On facing the death penalty at the end of the Rivonia Trial in April 1964.

“I stand here before you not as a prophet but as a humble servant of you, the people. Your tireless and heroic sacrifices have made it possible for me to be here today. I therefore place the remaining years of my life in your hands”

On his release from 27 years in prison in February 1990

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“For to be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others”

On freedom, in his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, 1994

“I learned that courage was not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it. I felt fear myself more times than I can remember, but I hid it behind a mask of boldness. The brave man is not he who does not feel afraid, but he who conquers that fear”

On courage, in the autobiography

“Never, never and never again shall it be that this beautiful land will again experience the oppression of one by another and suffer the indignity of being the skunk of the world”

At his inauguration as president of South Africa, May 1994

“Archbishop Tutu and I discussed this matter. He said to me, ‘Mr President, I think you are going well in everything except the way you dress’. ‘Well,’ I said to the archbishop, whom I respect very much, ‘Let’s not enter a discussion where there can be no solution’.”

Speaking about his penchant for colourful shirts, August 1995

“Death is something inevitable. When a man has done what he considers to be his duty to his people and his country, he can rest in peace. I believe I have made that effort and that is, therefore, why I will sleep for the eternity.”

On death, in an interview for the Academy Award-nominated 1996 documentary Mandela

WHAT THEY SAID

“A typical terrorist organisation”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMargaret Thatcher on the African National Congress in October 1987

“The BBC have just gone bananas … many will remember his record and the record of his wife as they take the podium. This hero worship is misplaced”

Conservative MP John Carlisle on the decision to broadcast footage from a tribute concert at Wembley Stadium in 1990

“How much longer will the Prime Minister allow herself to be kicked in the face by this black terrorist?”

Conservative MP Terry Dicks speaking after Mandela declined to meet Mrs Thatcher on a trip to London in 1990

“Mandela let us down. He agreed to a bad deal for the blacks. Economically we are still on the outside. The economy is very much white”

Mandela’s former wife Winnie, although she later distanced herself from the comments

“The criticism has been that he made too many concessions, while the real victims of apartheid still have to live with the consequences. He is a global icon, a great leader, but he was not perfect”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAdam Habib, vice chancellor of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, commenting on the suggestion that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission had in fact allowed the criminals of apartheid to evade justice

“Now all over the world there are three words which spoken together represent the triumph for freedom, democracy and hope for the future – they are President Nelson Mandela”

Former United States president Bill Clinton in 1994

READ MORE: