Rwanda: What is Rwanda like? Is Rwanda safe to visit, 30 years on from genocide that killed one million?

When Mark Fleming first visited Rwanda in 2008, he found a country still reeling from the genocide which had ripped it apart more than a decade earlier.

The nation was still deeply divided following the massacre of members of the Tutsi minority ethnic group by armed Hutu militias in 1994. Up to one million people are believed to have been slaughtered and an estimated 150,000 to 250,000 women were also raped during the 100 day ordeal, which came at the end of four years of civil war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"When I first went there, the genocide was still very raw,” says Mr Fleming, chairman of charity Scottish Football for Rwanda, which sends Scottish football coaches to train players and coaches to boost the sport in the country.

"Some of the massacre sites were still left as was: the blood stains were still there and there were soldiers on every street corner. Now, it is more about history, rather than what we would have seen then, which was an open wound.

"The country was a total mess.”

Thirty years after the genocide, it has seen a remarkable recovery, but is still scarred by its tumultuous past, both emotionally and politically.

A third of the size of Scotland, but with a population three times larger, the vast majority of Rwandans still live rurally, but struggle to grow enough food to survive. A large number of people still live well below the poverty line, with over half of the population living on less than $2 a day.

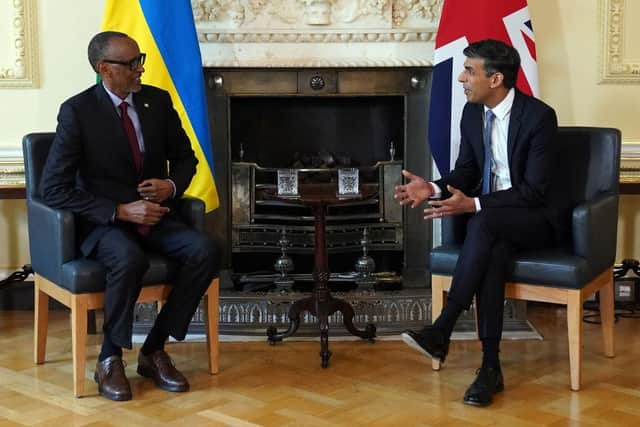

Now, the UK Government has passed legislation to revive its deportation scheme to Rwanda, after it was ruled unlawful by the Supreme Court last year. Despite the court warning that Rwanda is not a safe third country for asylum seekers, the government has pledged to press ahead with its scheme, which could see thousands of people who arrive in the UK through a non-legal route, such as on a small boat, sent to Rwanda for their case to be processed – and ultimately settled - there.

The UK Government has suggested Rwanda has been chosen for its track record in dealing with refugees from Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo - however the country has come under fire internationally for its human rights.

Home secretary James Cleverly admitted in an official document earlier this month that while Rwanda is now a “relatively peaceful country with respect for the rule of law, there are nevertheless issues with its human rights record around political opposition to the current regime, dissent and free speech”.

Surveillance is high in the country, with questions raised over freedom of speech. Meanwhile, Rwandan LGBTQ+ rights group Hope and Care Organisation has previously said that while homosexuality is not criminalised in the country, many LGBTQ+ people keep their sexuality and gender identity secret in an attempt to avoid rejection, discrimination and abuse. Same-sex relationships are not recognised.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

Mr Fleming, however, finds it to be a welcoming and tolerant nation.

"They are a very gentle, gracious people," he says. “And the recovery has been astonishing. I’ve seen terrific change every time I go out there. It really has become a second home.”

His connection with Rwanda began when a friend who worked for another charity, Comfort International, invited him to Rwanda to see the work the were doing supporting survivors of the massacre. He ended up meeting Rwandan footballer player Jacques Kayisire, who, as a Tutsi, had been protected by his predominantly Hutu teammates during the genocide.

As chaplain of the Scottish Football Association, Mr Fleming realised he could use his contacts to help create a training programme for Rwandan football coaches and began to visit every year with volunteer coaches from Scotland.

"The last time I was out there, the UK Government had announced its refugee plan, but no-one in Rwanda was taking it seriously,” he says. “They thought it would never happen.”

The Rwandan government, headed by Paul Kagame, is keen on the partnership. Rwanda has already been paid £240 million for its role in the scheme, with some debate over whether that money would be paid back to the UK if no refugees are ever sent there.

It has said the funds paid to Rwanda were intended to support the country's economic development as well as to "prepare to receive and care for the migrants when they arrive".

Tutsi Mr Kagame has led the country since his rebel force marched into the capital, Kigali, in 1994 to end the genocide and he has held the role of president since 2000. However, although technically a democracy with regular elections, the nation is essentially a one party state.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn both the 2017 and 2018 elections in Rwanda, irregularities in the vote tabulation process were criticised by international observers, while a US government human rights report published in 2022 warned that the Rwandan government “impeded the formation of political parties, restricted political party activities, and delayed or denied registration to local and international NGOs seeking to work on human rights, media freedom, or political advocacy”.

The next general elections are due to be held in Rwanda on 15 July this year, with Mr Kagame, who won 99 per cent of the vote last time around, planning to stand again to extend his 30 year rule, after a constitutional amendment in 2015 changed limits on the term allowed for a president to be in power. It is expected that he will once again win an overwhelming majority.

While Mr Kagame, regarded in the region as something of a “benevolent dictator”, has faced international criticism for allegations of the suppression of political opposition in Rwanda, he has also been praised for maintaining peace and creating economic growth during his time in power.

After the genocide, he introduced measures to try to build bridges between the Hutu and Tutsi communities, including the release of Hutus from prison, to finish their sentences carrying out community work to help rebuild communities decimated by the massacre.

"The new president recognised there would be ongoing recrimination and retaliation and wanted to stop that,” says Mr Fleming. “It was a massive risk, but it worked.

“When you are there, you don't feel that there is a dictator, you feel very safe.”

However, despite some successes, the country still battles to shake off its past. Mr Fleming’s wife, Aileen, a trained counsellor who works with survivors of human trafficking in Scotland, has accompanied him on many of his trips and has offered her services to people in Rwanda. The couple have also informally “adopted” a Rwandan woman who was orphaned during the genocide and was a teenage mother at the time they met her.

"One of the issues of the genocide is PTSD,” Mr Fleming says. “It is nearly 30 years ago now, but there are people under the age of 30 and born after the genocide, who are showing signs of PTSD, it has been passed down from their mothers who experienced trauma.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe adds: “It is not as raw as it once was, but it is still there.”

Marie-Eve Desrosiers, associate professor at the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs, at the University of Ottawa in Canada and author of recent book Trajectories of Authoritarianism in Rwanda: Elusive Control before the Genocide, says the country is still divided, despite apparent political harmony.

The government publishes a five-yearly Rwanda Reconciliation Barometer, which quizzes citizens on their views of tolerance and understanding of their fellow residents. The last survey, in 2020, found the overall score rose from five years earlier to 94.7 per cent.

"The government would tell you that it has achieved much in terms of reconciliation," she says. “But it depends how you define unity. It's certainly currently unified in terms of compliance behind this veil of coercive and strong, iron fist type of leadership, but once you start looking at what is going on, there is a lot of division."

She points to policies put in place by the government relating to areas such as agriculture, which she says benefit some groups more than others.

"In doing so, it has fed a lot of frustrations and resentment,” she says. “The government still favours certain groups; a lot of people in high positions will tend to be Tutsi.

"Although we tend to think of divides in Rwanda as predominantly ethnic, what has happened is fragmentation of some of these fault lines. In order to understand what is going on in Rwanda right now we need to move beyond Hutu-Tutsi to look at Tutsi as a group which is fragmented following the genocide.

“It wasn't just Hutu versus Tutsi, but an urban versus rural divide. There are all of these different cross cutting identities that create a very complex identity make up in a country which looks very small but is actually quite complex in terms of identity.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt also faces economic struggles. The World Bank’s profile of Rwanda points out that despite making “considerable progress in reducing poverty”, Rwanda has relatively higher poverty rates than African peers with similar income per capita, and poverty reduction has become less responsive to growth in recent years. The Scottish Government recently became the first high-income country to donate to the United Nations' Health4Life fund, which supports healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa, including Rwanda.

Its GDP growth averaged 7.2 per cent a year over the decade to 2019 and its government has invested in services, however, as a small, landlocked nation, its ability to attract incoming investment or export goods is limited.

"If you look at [economic growth] from 1994, you think this is pretty incredible," says Professor Desrosier. “But it has been an unequal division across the country. It also still relies heavily on international aid.”

Cathy Ratcliff, chief executive and and director of international programmes at Edinburgh charity EMMS International, says her organisation had been tasked with working with the Rwandan palliative care association, as well as those of other African nations – but says the group is hugely underfunded, indicating a wider poverty problem in the country.

"It's the least developed association that I have come across,” she says. “I think it’s got one laptop; they've got one very old vehicle. They've got two staff and a volunteer director.

"They don't have any accounts or policies, so we are developing those. It's hard to see what that indicates, but to me it certainly indicates that on the civil society side of their health care at least, they are very undeveloped.”

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.