'I would rather die than go to Rwanda' - the fears of LGBT+ asylum seekers in Scotland - Dani Garavelli

Racheal’s mother stopped paying her university fees (her father died when she was very young) and pushed her to get married. Her brother - a police officer - waged a campaign of terror against her. “He had a lot of connections,” Racheal tells me. “He would look for me everywhere. The first time he found out was when my school phoned home. He took me into a police cell. Later, he locked me in a store cupboard at home.”

For some years, Racheal tried to fight back. A beautiful, poised young woman, her family pushed her into modelling - “so I could be more ‘girly’,” she says. She used the money she won in beauty pageants to pay her own way through university, becoming an accountant and eventually securing a job at a small accountancy firm. “If I wasn’t a gay person and I had stayed in Uganda I think my future would have been bright. But they wanted me to pretend and I cannot pretend to be what I am not,” she says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe persecution never stopped. “It was hard to get accommodation, and then every day you were reading in the newspapers about how gay and lesbian people were being treated, so you were very scared.”

Racheal used some of the money she had saved to move to Scotland, securing a year-long visa and becoming a voluntary live-in carer in Inverness. She hoped her family would miss her and tell her to come home. Instead, her brother tracked down her address and started sending abusive messages. She became depressed, and it was suggested to her she should seek asylum.

That was in October 2020. Since then, she has been stuck in the system, waiting for a decision. Despite her poise, she is clearly stressed. She remains cut off from her family and doesn't know what has happened to her girlfriend.

What makes her most tearful, though, is talking about Home Secretary Priti Patel’s plan to send “illegal” asylum seekers on a one-way trip to Rwanda, which shares a border with Uganda.

Being LGBT+ is not a criminal offence in Rwanda. In its assessment report, the UK government said there were “not substantial grounds” for believing LGBT+ people would be at risk of treatment contrary to Article 3 (freedom from torture and inhuman or degrading treatment) of the European Convention of Human Rights.

And yet Foreign Office travel advice for the country states: “Individuals can experience discrimination and abuse, including from local authorities. There are no specific anti-discrimination laws that protect LGBT individuals.”

Last year, the organisation Human Rights Watch reported that the Rwandan authorities had rounded up and arbitrarily detained over a dozen gay and transgender people, sex workers, streets children and others before an international conference. “People interviewed who identified as gay or transgender said security officials accused them of ‘not representing Rwandan values’,” the report said. “They said other detainees beat them because of their clothes and their identity.”

And even the government's assessment admitted concerns over the treatment of some LGBTQI+ people in the east African country, and that investigations point to “ill treatment” of this group being more than one off.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The beliefs that are in Rwanda are the same beliefs that are in Uganda and Kenya and every other African country,” says Racheal. “If I had thought I would be safe in Rwanda then I would have caught a bus across the border - that would have been the easiest route for me. But I wouldn’t be safe. My brother has connections and he could find me. And there are people fleeing Rwanda for exactly the same reason.

“If the UK government sends members of the LGBT community to Rwanda, then it’s like they are signing their lives to be slaughtered.”

*************

I am talking to Racheal in a room in the Adelphi Centre in the Gorbals, Glasgow. She is one of a group of people - members of the third sector organisation LGBT Health and Wellbeing’s asylum seekers and refugee project - who have come to talk to me about their experience of the hostile environment policy, and their fears for the future.

Being LGBT+ is still a crime in 72 countries, with punishments ranging from imprisonment to the death penalty.

Having been through the system herself, development worker Stella Kyalikunda understands how difficult it is for those who have fled to cope with the asylum process which leaves them impoverished, stripped of dignity and often isolated even from their own ethnic groups.

“It is really unfair to treat humans the way the government treats us,” she says. “I am working with some people with no recourse to public funds. They are homeless and destitute, living on £8 a day. There are women who cannot afford sanitary products.”

Kyalikunda says LGBT+ asylum seekers experience an extra level of trauma, often continuing to face discrimination on the basis of their sexuality once they have reached the UK.

“There is a no choice basis on the accommodation, so they may be housed with people who are homophobic,” she says. But there is also ongoing prejudice from people from their own ethnic communities.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“They can’t be open because they will continue to discriminate against them,” Kyalikunda says. “I am a living example. I am from Uganda. I have Ugandans talk about me or they will talk behind my back. ‘Oh that is Stella who works with those people.’ I have tough skin. I am someone who can go: ‘Yes, this is Stella; so what?’ But there are many people who are scared of what will happen to them. I work with people who can’t even come to meetings because they are afraid someone from their community will find out.”

She says the mental health of LGBT+ asylum seekers and refugees is terrible. “We are seeing an increase of overdosing on medication, and drug and alcohol abuse while people are waiting on a decision,” she says. “By the time the decision comes, their mental health is so bad they can’t do anything.”

Their trauma is being increased by the UK policy over Rwanda. There is no clarity around who will be affected, or what will happen to them should their applications fail. Some of them have already been subject to repeated detentions. So it is no wonder they feel threatened by a policy which has not been properly explained, and may be in breach of international law.

“The Home Office itself has identified LGBT people are likely to face discrimination in Rwanda, but is going ahead anyway,” says Mark Kelvin, CEO of LGBT Health and Wellbeing. “The policy adds to those layers of trauma LGBT asylum seekers face in a way that goes to the root of who they are.

“Imagine you have found somewhere you finally feel you belong - maybe you feel like you have found your people. Now the UK government is saying: ‘This isn’t where you belong.' It is saying: ‘We don’t actually care what happens. Here’s a one-way ticket to a country we know you’ll be persecuted in. That’s how worthless you are'.”

************

Everyone in the room has suffered abuse because of their sexuality.

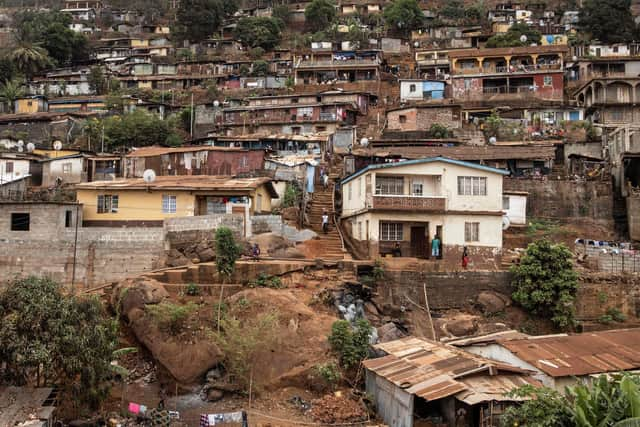

Mo, 20, who is bisexual, began a relationship with a British man who saw him playing football as a teenager in Sierra Leone. When his uncle found out, he said he would kill him.

He arrived in Scotland in March 2020. One day he was in his flat when there was a knock on the door and he was told he had to move to the Park Inn Hotel in Glasgow. Mo was one of the six people seriously injured there in the mass knife attack in June of that year. He was stabbed five times and still has ongoing health issues.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMo feels as if he “came out of the frying pan into the fire”. “It was like hell at home, but it is hell here. Sometimes I think I would rather go back but then I know my uncle would be waiting for me, so I stay and hope it will get better.”

Moses, from Malawi, is 25 and obviously fragile. His parents sent him to the UK because he had a boyfriend. When he arrived at Manchester Airport, he expected someone to pick him up, but they did not arrive. He was detained then and multiple times after. Those processing his asylum claim asked for evidence from his past to prove he was gay. “But I was in hiding in Malawi so I couldn’t give them any,” he says.

His initial claim was rejected and the Home Office attempted to deport him. As he was being taken to the airport he phoned Kyalikunda and the project intervened to halt it. Now he is making a fresh application. But he is living in temporary accommodation and his mental health is poor. “I am suffering depression, depression, depression,” he says. “My flat is temporary so every time I hear a noise I think there is someone at the door about to take me away.”

There are sunnier stories too, though. Ibrahim Kamara is 36 and loves fashion. He is wearing black and white tartan-esque trousers, a black shirt edged with a white trim and earrings which he pulls his lobes to show me.

As a child, he would braid his hair to match his sisters’ which marked him out at his all-boys school. Then he fell in love with a white German boyfriend and he became a target.

Kamara did not want to leave his Sierra Leone home. He had been trained, by the BBC, as a radio presenter and was working at Galaxy Radio in Freetown. He soon garnered a profile, and, having been taught journalists should exercise their freedom of speech, he started talking about LGBT issues.

“I was telling people they had the right to live the life they loved,” he says. The abuse grew. His dad attacked him, and he was prevented from praying at the mosque. He left to join another radio station, then moved from Freetown to Kambia on the border with Guinea.

But the abuse followed him to his new home. He pulls back his top lip to reveal slightly crooked teeth and a scar where he was punched. He went to the police who told him they’d have to lock him up and at that point he realised he had to leave.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdKamara's boyfriend helped him to get out of the country. He travelled to London, where he stayed for a while, but there was a big Sierra Leone community there and, once again, he found himself targeted.

A year and seven months ago, he moved to Glasgow. When he arrived, he was handcuffed and taken to a police station but the organisation Migrants Help put him in touch with a lawyer who is supporting him in his asylum application.

Kamara is still awaiting a decision but is upbeat because he can finally be himself. “I feel relief when I walk in the streets in Glasgow,” he says. “I joined LGBT Unity, I went on the Glasgow Pride march, the LEAP Sports festival fortnight and then I joined Vogue Scotland. Back home I couldn’t dress like this, I couldn’t wear these earrings. I started being happy because the people around me accept me for who I am.” He is also volunteering at a radio station in Govanhill. “I felt I was home, doing my thing,” he says.

Kamara says the first time he heard about the Rwanda policy he couldn’t sleep. “I was like, imagine there are some people in my country who didn’t have the opportunity to leave with a visa. Some of them will go from Sierra Leone through Guinea, and Senegal and Libya and, after all that, some will make it to the UK. Imagine going through all those borders and now they find themselves in the UK, thinking I am here for human protection. We still think the UK is the best country for human rights, but then the government says to these people: ‘We are sending you to Rwanda’.

“Maybe the government in Rwanda wants to make a deal with the UK, because maybe they need the money. They will say LGBT people will have a good time here but they won’t. It will be difficult for them; for some, it will be like killing them.”

**********

Beyond the walls of the Adelphi Centre, the controversy over the policy rages on. Last week, Patel said the first group of asylum seekers in the UK had already been notified of the intention to send them to Rwanda.

On Friday night, ITV News obtained documents which show those who face being sent there are to be given between seven and 14 days to provide reasons in writing as to why they shouldn't be deported.

The documents say: "If the journey you have made to the UK may be described as having been dangerous, you may be eligible for relocation." Those who have been detained have seven days to submit information, while those outside of detention have 14 days.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the same time, the policy is being fiercely opposed. The Public and Commercial Services union (PCS), along with charities Care4Calais and Detention Action, have launched a legal challenge on the grounds that Patel’s failure to disclose the eligibility criteria for being transferred to Rwanda is "an unlawful breach of her duty of transparency and the wider constitutional right of access to justice". They also argue the removal of asylum seekers from the UK to Rwanda would itself be unlawful, as the policy penalises individuals on the basis of irregular entry, in contravention of the Refugee Convention.

Freedom from Torture is seeking a judicial review of the policy. It argues the Home Office’s description of Rwanda as a safe country is “irrational”, and that the policy breaches human rights laws and the Refugee Convention.

And a small Nottingham-based law firm, InstaLaw, which specialises in public and international law, has also launched an action in connection with an Iranian asylum seeker who arrived in the UK in March and believes he will be amongst the first to be extradited.

At the time, Stuart Luke, a partner at the firm, said the Iranian would face extreme hardship if sent to Rwanda. "He could be the only Iranian in the country, there’s no network there, no community, no one who speaks the language. How’s he going to manage, survive? How’s he going to find a job, get educated?" he asked.

Kelvin points out the policy is discriminatory. “It’s blatantly racist,” he says. “The [University of Oxford-based] Migration Observatory has pointed out only a quarter of those seeking asylum come from African countries. And yet there is this idea that we are sending them back,” he says, “And then there is the fact that if the government was saying: 'Let’s send people from Ukraine to Rwanda' there would be a much bigger outcry about how inappropriate it was.”

In the meantime, uncertainty hangs like a pall over the asylum seeker members of the LGBT Health and Wellbeing project.

“It breaks my heart,” says Kyalikunda. “Coming from Uganda, I know the culture in Rwanda is the same. They do not like LGBT people, and they will not accept them. I am working with people whose mental health is so bad and they have told me point-blank: “I would rather die than go to Rwanda.

“I am so scared that will become a reality.”

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.