Deepwater Horizon disaster: Bugs ‘ate’ BP slick

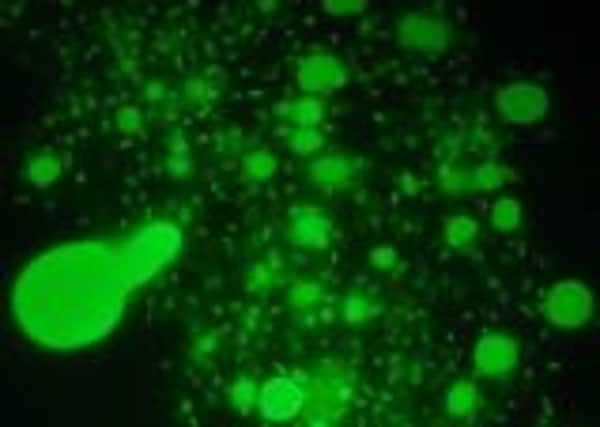

Scientists at Heriot Watt University working as part of an international team have found the first evidence that microscopic bugs which were found in vast numbers in slicks on the surface of the Gulf of Mexico spill were feeding on the oil.

The study confirms the belief among environmental experts that the organisms can have a significant impact on cleaning up oil spills naturally.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdResearchers are now analysing the genetic make-up of the most dominant bacteria, cycloclasticus, to find out more about how the bug breaks down oil and what conditions encourage feeding.

They hope the work could lead to the creation of new “fertiliser” treatments designed to provide the optimum nutrients needed to promote maximum feeding rates in the bacteria.

Dr Tony Gutierrez, associate professor at Heriot Watt’s School of Life Sciences, said: “Many big scientific papers have come out and shown the dominant types of bacteria in oil slicks, particularly at the Deepwater plume, but they have not confirmed that the bacteria were definitely using the oil as food and breaking down the hydrocarbons. This paper does that.

“We are the first to isolate the most dominant bacteria in the surface slicks, cycloclasticus, which accounted for about 90 per cent of the total bacteria found at the Deepwater spill, and to prove that it was breaking down the oil.

“Now we have that evidence, we are working to sequence its DNA to try to find out more about how it breaks down oil pollution. If we can find out which genes are involved it will improve our understanding of what could limit the bacteria’s ability to break down oil.

“You could have lots of oil and lots of bacteria but they might not break it down because they may need a particular ratio of nutrients, such as nitrogen or phosphate.

“What we find out could help create fertilisers which could be used to treat a spill by speeding up the breakdown of hydrocarbons by bacteria.”

The blow-out of the Deepwater Horizon well off the Louisiana coast in 2010 was the worst environmental disaster in US history and one of the most devastating worldwide, causing the deaths of 11 workers on the rig and spewing more than four million barrels of crude oil into the Gulf over a period of nearly three months.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShorelines were polluted from Texas to Florida as a vast slick spread over around 20 miles.

It caused widespread damage to wildlife and habitats and massive losses to the fishing and tourism industries, forcing operator BP to agree a multibillion-dollar compensation deal in 2012.

The Heriot-Watt research was based on analysis of water samples taken by a PhD student from the university who was among the experts on the first research ship to reach the site of the spill.

Scientists used specialist techniques to mark carbon molecules in the hydrocarbons from the slick to reveal which bacteria had ingested the oil.

Cycloclasticus accounted for the majority of oil taken in by the micro-organisms, while similar bacteria, Alteromonas and Halomonas, were also found to have ingested oil at the spill.

Dr David Green, microbiologist at the Scottish Association for Marine Science in Oban, said the research provided key evidence improving understanding of which organisms were involved in breaking down the toxic hydrocarbons present in crude oil.

He added: “[The study] suggests that the whole community [of organisms] working together may be important for cleaning up oil spills. These research findings support my research hypothesis that a healthy, productive and diverse ecosystem is likely to be better at recovering from an oil spill than a more degraded ecosystem.”

However environmentalists warned that the findings were unlikely to save wildlife from any future disasters on the scale of Deepwater or Braer, Scotland’s worst-ever oil spill where around 85,000 tonnes of crude oil leaked into the sea after the Liberian-registered tanker ran aground off Shetland in 1993.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Richard Dixon, director of Friends of the Earth Scotland, said: “I think it’s good news that nature is so clever that it can even ‘eat’ oil, but even if we got really good at manipulating that I think the impact would be small.

“It might be promising for cleaning up small spills or the last remnants of a big spill but I don’t think it could be deployed on the kind of scale needed to deal with the devastation to wildlife and the seas caused by a major incident.”

The 20th anniversary of the Braer disaster earlier this year brought renewed warnings from environmentalists that another marine catastrophe was “never far away” due to the combined risk of safety cutbacks and record levels of North Sea drilling.

In 2011, a leaking pipeline at oil giant Shell’s Gannett Alpha platform, around 100 miles east of Aberdeen, caused the UK’s worst oil spill for a decade.

The research is due to be published in the International Society for Microbial Ecology journal later this year. It was carried out with experts from the universities of North Carolina in the US and Vienna in Austria.

Twitter: @ScotsmanJulia