UK muslims feel identity under threat since 9/11

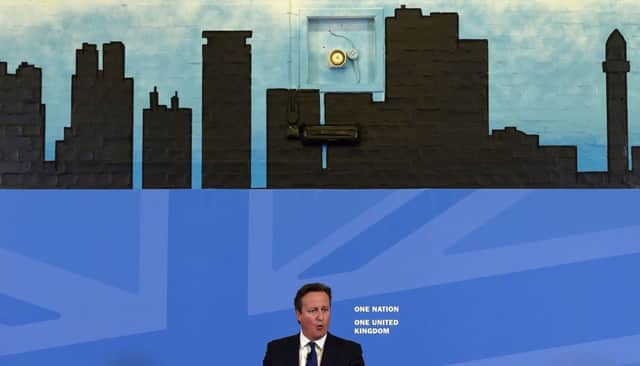

It is a subject so complex that the usual rules of politics don’t apply. When Prime Minister David Cameron set out his five-year counter-extremism strategy last week, even those who might usually be expected to criticise for the sake of criticism were unable to do so.

Take SNP MSP Humza Yousaf, Minister for Europe and International Development in the Scottish Government. Yousaf, a practising Muslim, said that there was “much to be welcomed” in the Prime Minister’s speech outlining the UK Government’s plans to take on those who use a professed devotion to Islam to excuse acts of murderous terrorism.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYousaf – a sworn political enemy of the Tory party – is clearly sympathetic to the challenges Cameron faces, particularly in the aftermath of last month’s slaughter on a Tunisian beach, when a gunman claiming allegiance to the Isis group killed 38 people, including 30 Britons.

The majority of headlines were grabbed by Cameron’s announcement that parents worried that their children may be about to travel to Syria or Iraq to join Isis – as a number of young Britons have – will be able to apply to have their passports cancelled. The right will apply to parents of all children under 16.

But there was much more in Cameron’s speech, in which he stressed that Islam had become, in a number of cases, a cover for violent extremism. It was, said the Prime Minister, necessary for the state to side with moderate Muslims in what he described as a battle of ideas.

He said there was a need for difficult conversations about so-called “honour” violence and female genital mutilation. Britain had to “confront a tragic truth that there are people born and raised in this country who don’t really identify with Britain – and feel little or no attachment to other people here”.

“Indeed, there is a danger in some of our communities that you can go your whole life and have little to do with other religions and communities,” he said.

Cameron said that groups like Isis could offer to some young British Muslims a sense of belonging that may currently be missing from their lives, adding: “Islamic extremism is a radical, exciting, even glamorous ideology that gains traction due to the failures of integration.”

Yousaf praised the positive language in the Prime Minister’s speech, which he said showed an attempt to engage with a difficult subject and bring together the state and the Muslim community.

But he pointed to what he believes is the greatest problem faced by both those of the faith he practises and the UK government – a belief that the generation of extremism is caused only by “one side or the other”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Where I have trouble,” said the MSP, “is that when it comes to the radicalisation of young Muslims, each – the Muslim community and the political establishment – blames the other.

“Until we grasp that there is a mixture of factors, then we won’t make progress. There are external factors – the war in Iraq, the Middle East crisis – that may cause some young Muslims to become radical. But there are also internal factors from within the Muslim community.”

Yousaf said there were hard questions for Muslims in Scotland to consider when it comes to radicalisation of young people. As the Scottish Muslim Heritage Trust campaigns to raise awareness of the positive contribution followers of Islam have made to Scotland, Yousaf said there was a need for some introspection, too.

“In my experience, the majority of Muslims believe only that the external factors I mentioned are to blame. They don’t want to combat the internal factors.”

For Muslims in Scotland, and all over the world, their faith is going though one of the biggest challenges in its history, said Yousaf.

“There are those who believe scripture to the letter and want to follow the text as it was followed back 1,400 years ago, and then there are others, moderate Muslims, who believe in a different way of following the faith.”

Former deputy leader of the Scottish Labour Party, Anas Sarwar – now pursuing business interests since losing his parliamentary seat in the general election – says that Scotland’s Muslim community may be less susceptible to the influences which have radicalised young Britons but counsels against the idea that we are, as a nation, immune to them.

“Traditionally, in our Scottish psyche, we like to believe that we’re more welcoming and find it easier to integrate than others,” he said. “Look at Glasgow, where I was born, and you see people socialise across communities in a way you don’t see so much in Birmingham, Bradford, or Manchester.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But while we might reassure ourselves that we are more likely to integrate, we have seen examples of Scots going to fight for Isis. This is a problem that also affects us.”

One advantage Scotland has when it comes to dealing with the threat of radicalisation, said Sarwar, was that most Imams were born here and have English as their first language, rather than their second or third.

“We don’t have preachers coming here to describe a distorted version of the faith, we have people born here who understand the culture of this country and how the traditions of our faith can sit with that.”

Like Yousaf, Sarwar believes it is essential for all engaged in tackling the threat of radicalisation to understand the complex mixture of motivations that can lie behind it.

“The problem David Cameron faces,” he said, “is that there is no one-size-fits-all description for what makes someone radicalised and, therefore, no one-size-fits-all solution. Some come to that place through an interpretation of their faith while others lose their faith and find themselves in the same place. Others are angry about something that has happened overseas, while some are angry about something that has happened here, at home. There are so many different possible explanations.”

Sarwar said that, while Cameron had led his speech with tough lines about passport cancellations, the best chance of finding a solution to the problem of radicalisation was for Islamic leaders and politicians to work together to avoid creating a sense of injustice.

“I’m certainly not saying that the grievances some might cite as reasons for their actions in any way justify those actions but we can do more to combat the perception of injustice.”

Yousaf also highlights the belief among young members of the Muslim community that they might be at risk of persecution by authorities as a problem.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“My office is in Glasgow city centre so I do my Friday prayers at the Strathclyde University Mosque and every week, I’m approached by Muslim students who want to know, ‘Is the government spying on us?’, ‘Is it cracking down on us?’ We need to do something about that perception.”

Yousaf said it was essential that those who followed a more traditional form of Islam felt able to express their views.

“I class myself as a moderate, but there are others who follow a more conservative strand of Islam and I support their right to do that and to speak up. We can’t have freedoms for one and not the other.”

But while Yousaf supports the right of conservative Muslims to follow a more traditional reading of scripture, it is clear that he believes Islam requires a radical shift into the 21st century. “There are absolutely difficult questions for the Muslim community in Scotland to face up to,” he said.

“The main mosques in Scotland don’t have a single female committee member among them, for example. That’s something that should change. At the moment we have the same middle-aged men running mosques and we need a broader, more diverse mix of committee members. Are we engaging enough young people and tackling views that some of us disagree with?”

Cameron’s speech last Monday was brimming with tough rhetoric which, in some instances, threw up contradictions.

He said, for example, that one of the aims of the counter-extremism strategy due to be published in the autumn would be to stop extremist agitators who are “careful to operate inside the law”. It is difficult to see how that might be achieved if no laws are currently being broken.

Yousaf said that, in his view, the Muslim community in Scotland had a good relationship with the police and that it was important to protect that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCameron also said that he would legislate for lifetime anonymity for victims of forced marriage in order to increase reporting of such crimes, and he promised new measures to guard against the radicalisation of children in so-called supplementary schools or tuition centres.

And he reiterated that new action needed to be taken to empower broadcasting regulators to prevent access from the UK to foreign TV channels that air the views of hate preachers and extremists. It was difficult to listen to that particular promise without wondering how such a move would prevent young people from accessing dangerous material on the internet.

And there were moments in the speech that may have made some who argue that Islam and extremism are unconnected uncomfortable or even angry. Cameron said Britain had to stop pretending there was “no link between extremism and Islam because the extremists are self-identifying as Muslims”.

He said: “The fact is that from Woolwich to Tunisia, from Ottawa to Bali, these murderers all spout the same twisted narrative, one that claims to be based on a particular faith. It is an exercise in futility to deny that and, more than that, can be dangerous.”

“To deny it has anything to do with Islam means you disempower the critical reforming voices – the voices that are challenging the fusing of religion and politics, that want to challenge the scriptural basis which extremists claim to be acting on.”

Yousaf said that those concerned about radicalisation should be mindful of the pressure Muslims felt “post 9-11”.

“My perception is that since then many Muslims feel that their identity is under threat in a way it never was.

“We see it in different ways, throwaway remarks. My mum wears a headscarf, for example, and she has had more comments directed against her in recent years. My aunt was in Homebase recently and asked another customer if he would hand her something down from a shelf. He said he would as long as she wouldn’t bomb him.”

Not, perhaps, enough to radicalise a middle-aged woman of moderate views, but an example of the change in mood that may be adding to the frustration some misguided young Muslims undoubtedly feel.