Soldier suicides kill more than Afghan weapons

The Ministry of Defence confirmed that in 2012, seven serving soldiers were confirmed to have killed themselves, while a further 14 died in suspected suicides where inquests had yet to be held. The government does not record suicides among former soldiers, but an investigation by the BBC’s Panorama found at least 29 veterans also took their own lives last year.

The total of 50 suicides compares with 40 soldiers who died in action in Afghanistan during the same period.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA spokesman for the Ministry of Defence (MoD) said suicide among members of the armed forces was “extremely rare”.

But former senior officers said they believed the issue was worse than was acknowledged.

Colonel Stuart Tootal, a former commander of 3 Para, said: “The evidence suggests there’s more of a problem than the government and the MoD are admitting to.”

The recently retired head of the British army, General Sir Richard Dannatt, has called for the suicide rate among veterans to be monitored. He said: “It’s pretty clear to me that it should be happening, because once you have some statistics you can start to do something about it.”

Labour has been pushing the government to strengthen its military covenant and take the mental health of soldiers more seriously, particularly of those who have served in combat.

Labour’s shadow defence secretary Jim Murphy said: “It is essential that this information is used as the basis for a full assessment of the post-service support our personnel receive, especially mental health support.

“Our responsibility to service personnel does not end after they leave the battlefield. They should not be isolated when tackling the invisible injury of mental health problems caused by exposure to conflict.”

Panorama said it wrote to every coroner in the country to ask for the names of soldiers and veterans who took their own lives last year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere is added pain for the families of personnel who killed themselves after ending their tours of duty. While the names of those who kill themselves on duty are engraved on a national memorial to military casualties, the same is not done for those who die out of uniform.

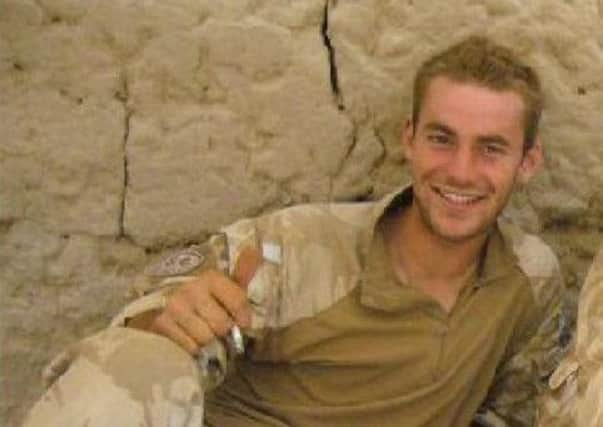

Lance-Sergeant Dan Collins, who survived a bomb blast while serving in Helmand province in Afghanistan in 2009, killed himself while still a serving soldier on New Year’s Eve 2011, after suffering with post- traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the BBC reported. His mother, Deana, told Panorama her son was a “victim of war” and his name should be added to the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire, which honours the casualties of every conflict since the Second World War.

“Soldiers with PTSD are exactly the same. They’re victims of war and they should be treated exactly the same,” she said.

An MoD spokesman said: “Suicide amongst members of the armed forces remains extremely rare and is lower than comparative rates in the civilian population.

“Mental health of our personnel and veterans is a top priority for the government and that is why £7.4 million has been committed to ensure there is mental health support in place for everyone who needs it.”

He also pointed to research published by Kings College London, which shows a lower rate of suicide and self-harm in those who have served in the armed services than the equivalent age group in society as a whole.

The research revealed that the prevalence of reported self-harm in the UK military was 2.3 per cent, lower than the 4.9 per cent reported among the general population.

The MoD spokesman said: “Medical experts working in our armed forces and the NHS are committed to ensuring a smooth transition from the armed forces into the NHS.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“This includes improving the transfer of medical records on discharge to provide better continuity of care and providing mental health assessments prior to discharge.”

However, clinical psychologist Dr Claudia Herbert said PTSD was the body’s “natural response” to distressing events such as combat situations.

She said the condition could take years to emerge, but was treatable if caught early. Symptoms included flashbacks, severe anxiety and depression.

Dr Herbert said: “Post-traumatic stress disorder in itself should not lead to suicide.

“PTSD is a condition that indicates something has deeply disturbed the system and is a warning that the system needs help and needs to regulate again.”

The Kings College study also raised concerns about the effects on regular soldiers who leave active service. The issue has become more acute in the past few years, as the government is making 20,000 soldiers redundant.

Grim statistics

166 Afghanistan veterans are being supported in Scotland by Combat Stress, the organisation that helps personnel and veterans after active duty

90 Iraq veterans are being supported by Combat Stress in Scotland

5,200 total UK caseloads for Combat Stress

7 Known suicides of serving personnel in 2012

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad14 Suspected suicides of serving personnel in 2012, pending inquests

29 veterans found to have killed themselves in 2012 by Panorama

2.3 per cent suicide and self-harm rate among military personnel, according to Kings College London

4.9 per cent suicide and self-harm rate in the general population for the same age group

134,780 soldiers have been deployed to Afghanistan since 2001

£7.4m committed by MoD to mental health care for service personnel

Case study: Black Watch soldier’s call for help was never answered

BLACK Watch soldier Aaron Black, from Perthshire, was found to have killed himself in December 2011 after leaving the forces.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSeven months after he was discharged, Mr Black, 22, from Rattray, near Blaigowrie, in Perthshire, surrounded himself with treasured photographs, including a picture of a former girlfriend, his army medals and a crucifix.

He sent a last text message to his mother before hanging himself.

His mother, June, demanded a fatal accident inquiry into his death in a bid to prevent similar tragedies.

She believes there was a “systematic failure” in getting her son the help he needed after he returned to the UK from duty in Afghanistan.

Medical records show that Mr Black had been suffering from “depressive symptoms and trauma symptoms from Afghanistan, is still jumpy, with dreams and flashbacks”.

The records add: “He continues to have suicidal thinking, accepting it is worse when he has been drinking.”

According to the records, Mr Black was referred by a consultant psychiatrist to a community mental health nurse for “trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy” before his discharge from the army, but missed his second appointment.

The records state that Mr Black would then have been referred to a mental health social worker at RAF Leuchars before he left the army.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, Mrs Black claims that no contact was ever made with her son.

Analysis by Andrew Cameron: We must not neglect mental wellbeing of our veterans

Every suicide is one too many, but 50 in one year is desperately sad. More than 200,000 soldiers have served in Iraq or Afghanistan during the last decade. We expect that one in five will suffer from some form of mental illness, with between four and seven per cent suffering from the more serious and life-limiting post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

These people will need support but they must be able to access it quickly and easily if we are to prevent further tragedies.

Demand from veterans seeking mental health support is increasing. The charity sector and the NHS must manage this challenge together.

The NHS has a crucial role to play in ensuring soldiers and veterans access the support they need. Eight in ten veterans we treat have tried to access NHS services but found them ineffective or lacking understanding.

If we are to prevent a national tragedy, then more must be done to ensure NHS clinicians are equipped to deal with veterans’ unique experience of battle trauma and service life.

Generally speaking, NHS and emergency services staff are the first to have contact with veterans who are in deep emotional turmoil.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFurthermore, developing NHS veterans’ mental health services are patchy and we need to assess what practices are effective and what are not. Best practice needs to be spread nationally to provide knowledgeable, effective coverage.

Combat Stress is working closely with the Ministry of Defence and Department of Health to develop these services now because the challenge will continue to increase post conflict.

Those who have sacrificed so much to protect our freedoms deserve our respect and support. This report is a wake-up call for us all and the situation will only get worse if action is not taken. As a country we can do better – and must do better.

• Commodore Andrew Cameron is chief executive of Combat Stress