Scottish scientists first to map brown dwarf

The team at the University of Edinburgh mapped the surface of a brown dwarf – an object larger than a planet and smaller than a star.

Luhman 16B has up to 25 per cent of its visible surface covered in a hurricane-force storm, it was revealed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdResearchers discovered that the brown dwarf, located around six and a half light years from the sun, has a complex structure of patchy clouds made up of droplets of liquid iron and other minerals, with temperatures in the clouds exceeding 1,000°C.

“Weather reports” have previously been received from Mars, Venus, Titan and other bodies in the solar system but this research is unique in observing such detailed phenomena from so far away.

Brown dwarves are sometimes knows as “failed stars” because of their inability to muster enough mass to become stars. Their gravity is not strong enough to compress and heat their centres to a level allowing a fusion reaction to start, which releases energy to light up stars.

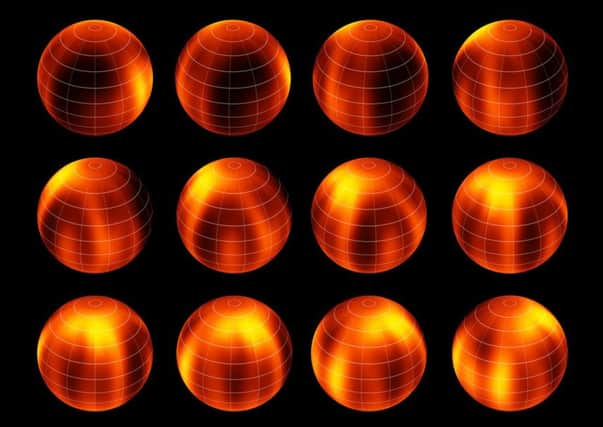

High resolution pictures reveal a full rotation weather map of the brown dwarf over its five-hour day.

Scientists said the discovery and methods used in their study could eventually be applied to examine small, cool planets in other solar systems to better understand their weather patterns.

The brown dwarf is too far away for direct images of its surface to be captured, so the team applied a number of novel techniques using two telescopes at the European Southern Observatory – situated in the Atacama Desert in Chile – to analyse its atmosphere.

As Luhman 16B rotated, bright and dark clouds were seen moving in and out of view and its brightness changed.

The team observed changes in the brown dwarf’s intensity and were able to reconstruct what happens in different layers of its atmosphere.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Beth Biller, of the university’s school of physics and astronomy, who led of the international project which included universities in France and Germany, said: “We are excited by what we have been able to see in these studies, but this is only the start. With new generations of telescopes, such as the forthcoming European Extremely Large Telescope, astronomers will likely see surface maps of more distant brown dwarfs and eventually, surface maps for young giant planets.”

The university’s research on the brown dwarf is published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Professor John Brown, astronomer royal for Scotland, said: “The rate of progress in astronomy never ceases to amaze me. In under 20 years since the first detection of brown dwarfs – those halfway houses between planets and stars – we are now studying their weather and Dr Biller can be proud of pushing back the forefronts of such knowledge.

“In fact, brown dwarfs have been a hot – or should I say warm? – topic at ROE [The Royal Observatory, Edinburgh] since their discovery.”