Scottish innovations that changed the world

It is the nation that pioneered animal cloning, changed the face of communication with the invention of the telephone, and it was home to the iconic Hillman Imp, which was dubbed “Scotland’s answer to the Mini”.

Scotland has world-leading universities, colleges and research institutes which today are paving the way for exciting developments in everything from food science to big data, aquaculture and oil and gas technology.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHistorically, they have educated and benefited from the discoveries of some of the world’s most renowned innovators and inventors.

Professor John Macleod held the chair of physiology at Aberdeen University until his death in 1935. He is credited with the co-discovery of insulin as a treatment for diabetes, the research he undertook while working at the Toronto University in 1922.

James Young Simpson was a student at Edinburgh University and passed his exams at the College of Surgeons before making a name for himself in obstetrics. The Scot is probably best known for his work in anaesthesia, discovering a use for chloroform in childbirth and other surgical procedures.

“The introduction of chloroform is interesting because Simpson self-experimented,” says Iain Milne, Sibbald librarian at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

“Ether was discovered in America in 1846 and Simpson was one of the first to use it. He was one of those well-educated Scottish scientists who were keen to try all the latest things.

“There were disadvantages to ether – it wasn’t very nice to administer and it was highly volatile. Before that there was no decent anaesthetic – it would have been alcohol or opium that was used to numb the pain.

“You couldn’t do complex surgery because it was just too painful for the patient. Anaesthesia revolutionised things.”

Simpson was determined to discover an alternative to ether and he succeeded in 1847 while experimenting with chloroform with colleagues at his home at 52 Queen Street in Edinburgh.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Simpson was the first person to use chloroform in a surgical operation,” says Milne. “The chloroform he used was provided by Duncan Flockhart & Co, the Edinburgh chemist. We have the Edinburgh Maternity Hospital records here and you can see where, in 1847, chloroform starts to be used.

“Simpson was a real celebrity doctor. His funeral in Edinburgh was the largest public funeral Edinburgh has seen.”

Many of Scotland’s most famous inventions are on display in the science and technology galleries at the National Museum of Scotland.

Dolly the Sheep is one of the museum’s most iconic exhibits. Her birth was of huge excitement to the scientific world and to the public.

“It’s been over 20 years since Dolly, the first mammal cloned from an adult cell, was born at Roslin Institute near Edinburgh,” explains Sophie Goggins, curator of biomedical science at National Museums Scotland.

“Dolly’s birth showed that cells can be reprogrammed to function as different cell types.

“This was an important step for stem cell research, which could be used for new stem cell therapies, for instance creating organs for transplant that your body wouldn’t reject.”

Dolly’s birth opened up new opportunities in stem cell research.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Embryonic stem cells can generate every type of cell within the body, so by making stem cells from adult cells perhaps one day we will be able to grow replacement organs or help regenerate damaged ones,” says Goggins.

“Stem cell therapy has already been used for repairing eyes, skin grafts and rebuilding the body’s immune system.”

Professor Ian Wilmut led the research group that cloned Dolly in 1996; she was the only live lamb produced from 277 reconstructed eggs.

“The Roslin Institute no longer clones animals but uses the skills and experience gained from Dolly to grow their research,” says Goggins.

“One of the hopes for cloning is that it would provide a way of reproducing a genetically engineered animal.

“However, improvements in genetic engineering have made it more feasible to repeat the genetic manipulation rather than clone a single animal.”

Radar, or “radiolocation” as it was first known, was the result of experiments carried out from 1935 onwards in the back of a lorry on a country road near Daventry, in Northamptonshire, by Brechin-born scientist Robert Alexander Watson Watt.

It quickly became Britain’s “secret weapon” during the Second World War, alerting the army, navy and Royal Air Force to the presence of enemy ships and planes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe stone plaque marking the birthplace of Alexander Graham Bell can be spotted by the door of 14 South Charlotte Street in Edinburgh, highlighting yet another Scottish success story.

Bell was working at a school for the deaf when he invented the telephone, a device which he patented in 1876.

For years scientists had attempted to solve what they called the “problem of telephonic communication” but it was the Scot who was able to lay claim to the official title.

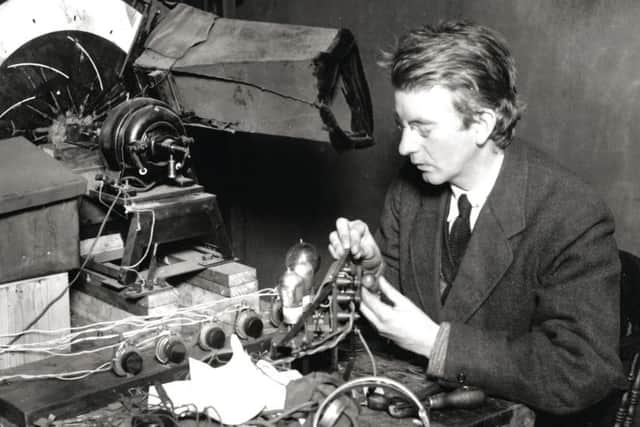

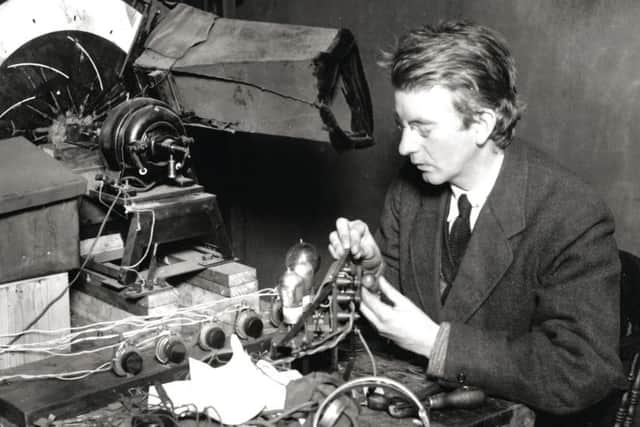

Reeling off a list of popular Scottish inventions, the television would probably come top of the pile. John Logie Baird’s “televisor” was first mentioned in The Scotsman in 1926, although the original contraption was a far cry from today’s flat-screen HD televisions.

“During the 1920s Baird was the first person to transmit experimental TV pictures along a wire and through the air using radio waves,” explains Alison Taubman, principal curator of communications at National Museums Scotland. “He called it ‘seeing by wireless’.”

Baird’s television was first demonstrated to the public at Selfridges store in Oxford Street, London, in April 1925, although much of his pioneering work was carried out in Scotland.

“Around October 1926, Baird gave a demonstration in the Temperance Café in Falkirk with his friend John Hart, who had a radio shop in the town,” says Taubman.

“On 24 May, 1927, he transmitted pictures down telephone lines from London to the Central Station Hotel, Glasgow. In February 1928, he transmitted pictures from London to New York – the beginning of world TV broadcasting.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBaird’s invention continued to develop and in 1929, he founded a television system for the home, which he called a “televisor”. It certainly wasn’t cheap, with only the wealthiest households able to afford one.

The televisor became available for the first BBC broadcasts in the 1930s and by 1932, 1,000 of the devices had been sold. Today, 95 per cent of UK households own a television.

“Today, Baird’s name remains linked to the experimental days of electro-mechanical systems, such as his pioneering televisor, a system which was dropped by the BBC in favour of an electronic system which became the norm we remember as the old cathode ray tube TVs, before the flat screens of today,” says Taubman.

“But Baird was also at the forefront of the development of electronic television, cementing his position as a true television pioneer.

“Just before his death in 1946, he was developing an all-electronic 1,800-line, three-dimensional colour television system.

“He died too early to witness the true television age from the 1950s but did succeed in taking out many patents for television and related subjects.”

Scotland has had its fair share of medical breakthroughs, from the work of the leading anatomist Dr Robert Knox – who is perhaps better known now for his involvement in the infamous Burke and Hare murders – to the discovery of penicillin in 1928 by Ayrshire-born physician Sir Alexander Fleming.

“I think because of the link to medical education in Scotland, which has been strong since the 18th century, you could say Scotland has a strong history of medical innovation,” says Milne.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe highlights the work of leading physicians including Sir John Crofton who combined streptomycin with other drugs to find a cure for tuberculosis.

“In the 1950s tuberculosis was still a much-feared disease which was often incurable,” says Milne.

“Crofton’s study was one of the first ever randomised controlled trial. In 1900, TB had been responsible for 155 deaths per 1,000 but by the end of the 20th century that was one per 100,000.”

It was pioneering work, as was the discovery of a vaccine for hepatitis B by Sir Kenneth Murray at Edinburgh University in 1978, and Sir James Black’s discovery of propranolol – or beta blockers – in the 1960s.

Also among the long list of leading Scottish innovators is Sir Ian Donald. The Glasgow gynaecologist was inspired by the use of ultrasound machines in shipyards to check welds and considered its use for prenatal scans.

“This was using industrial innovation for medical use,” says Milne. “It was a big radiological advance.”

Born in Edinburgh in 1831, James Clerk Maxwell is considered to be one of the most influential scientists of all time. “His research confirmed and expanded previous theories about the colour sensors in our eyes and he drew upon this to, in 1855, suggest that a photograph could be taken that would appear fully coloured, using black and white photography,” explains Tacye Phillipson, senior curator, modern science at National Museums Scotland.

To do this, three separate images would be taken, each through a different coloured filter; red, green and violet. These slides would then be paired with their respective filters, and the resulting image appears nearly fully coloured.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis work was acknowledged by Albert Einstein, who stated that the origins of the special theory of relativity lay in Maxwell’s theories. He is reported to have said: “The work of James Clerk Maxwell changed the world forever.”