Psychologist reflects on Apollo moon landing

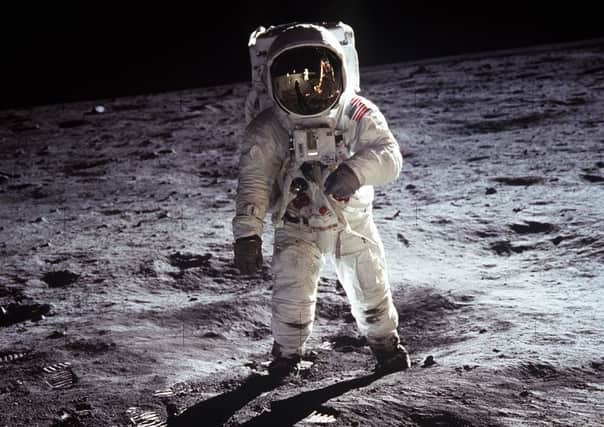

Most of the controllers came from modest, working-class backgrounds, and were often the first in their families to go to college. Perhaps most surprising of all, they were astonishingly young. In fact, when Neil Armstrong set foot on the Moon, the average age of the mission controllers was just 26 years. The group had few of the qualities that we commonly associate with success and yet, somehow, they managed to accomplish the seemingly impossible.

I wanted to discover why, from a psychological perspective, Mission Control was such a hotbed of success, and I was fortunate enough to be given the opportunity to interview several key controllers. Now in their seventies and eighties, they were all remarkably generous with their time and thoughts. I eventually discovered that their breath-taking achievement was due to a unique mindset partly inspired by the charisma and determination of President Kennedy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1958, the Eisenhower administration established the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), ploughing millions of dollars into science education. Two years later, John F Kennedy went head to head with Richard Nixon for the American Presidency. The space race took centre stage, with Kennedy pledging that he would do his best to ensure that America would be first across the finishing line. Kennedy won the day, beating Nixon to the presidency with one of the smallest margins in American history.

Kennedy had energy and determination and spoke to a post-war generation that seemed to have lost its way. The young President encouraged every American to reflect on how they could help others and emphasised the value of public service. His inaugural speech ended with a phrase that beautifully encapsulated Kennedy’s bold vision: ‘Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.’

The President knew that he needed a vision that would engage the hearts and minds of millions of people. He wanted to think bigger and bolder. After many months of meetings, the President eventually supported an idea that resonated with his grand sensibilities: the world’s first manned mission to the Moon. Mindful of the Russians beating America to the punch, Kennedy added a tough time frame, declaring that he wanted a man to walk on the lunar surface before the end of the decade. It was an astonishingly audacious aim.

On 12 September 1962, Kennedy travelled to Rice University’s football stadium to announce his dream of humans reaching the Moon before the decade was out. The event attracted an audience of over 40,000 people. Sitting up in the stands that day was a 15-year-old schoolboy named Terry O’Rourke. Now in his seventies, Terry still remembers seeing Kennedy: “You live thousands of days in your life, but I still have a vivid memory of those few hours.” Terry remembers the stadium being energised by Kennedy’s sense of passion and enthusiasm: ‘I had 100 per cent confidence in him. He said we were going to go to the Moon and I totally believed him. We all believed him. You can call it optimism, or arrogance, or innocence, but it seemed as if everyone in that stadium really thought that America could pull it off.’

Standing a short distance away from Terry was Rice University student and ace basketball player Jerry Woodfill. Originally from Indiana, Jerry had developed a childhood fascination with basketball and eventually won an athletics scholarship to Rice University. Jerry went along to hear Kennedy speak and, like O’Rourke, can remember the blistering heat. At the time, Jerry’s life was not going especially well. He hadn’t obtained great marks in his exams and his basketball training was proving tough. As Kennedy started to speak, Jerry felt something inside him stir. By the end of the speech, he was a changed man. Energised by Kennedy’s passionate vision of being the first to go to the Moon, Jerry returned to Rice University and dropped his basketball career, instead devoting himself to studying electrical engineering. When he graduated, Jerry applied to NASA and was invited to help develop the safety systems on the spacecraft that would attempt to land on the Moon. On 20 July 1969, just seven years after seeing Kennedy speak at Rice University, Jerry was working in the Manned Spacecraft Center, and helping Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the lunar surface.

Millions of people across America were inspired and enthused by Kennedy’s vision of going to the Moon, and soon it seemed as if the whole nation was suffering from space fever. Like Kennedy, Americans believed that heading into the heavens would promote freedom and democracy, and so help create a better world for future generations.

The same sense of passion motivated many of the scientists and engineers who would eventually transform Kennedy’s vision into a reality, and it was essential to their eventual success. When Flight Director Glynn Lunney was asked about how he felt about being part of the team that eventually put Neil Armstrong on the Moon, he responded: “We loved it. We loved the work, we loved the comradeship, we loved the competition, we loved the sense of doing something that was important to our fellow Americans.” Similarly, Flight Controller Steve Bales said that being part of the Apollo missions was so exciting and so much fun, that he would have worked on the programme even if he had only been paid enough to cover his living expenses. The controllers’ comments are supported by a wealth of scientific evidence.

Robert Vallerand, from the University of Quebec, has produced hundreds of academic papers on the psychology of passion. After studying the lives and minds of thousands of passionate people, Vallerand has discovered that this often-overlooked factor is one of the main secrets of success. When people do what they love, their work feels more like play and they are more likely to keep going when the going gets tough. As a result, they end up being especially productive and successful. In the same way that Kennedy energised an entire nation by announcing his intent to go to the Moon, passion has the power to propel people to incredible heights in both their personal and professional lives. Discovering and unlocking your passion is the key to finding satisfaction in all aspects of your life.

Adapted from Shoot for the Moon: Achieve the Impossible with the Apollo Mindset by Richard Wiseman (Quercus, £20.) Out today.