Susan Dalgety: After year-long tour of Europe, desire for a shared future is clear

I have just returned home after a year-long odyssey to every country in the European Union. Yes, all 28, and Serbia.

My husband and I discussed the fall-out of the 2008 crash with rich Luxembourg bankers and mused about migration with sceptical Germans and happy Somalians.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe even eavesdropped on Nigel Farage enjoying a pint (or several) in the bar of the European Parliament in Strasbourg.

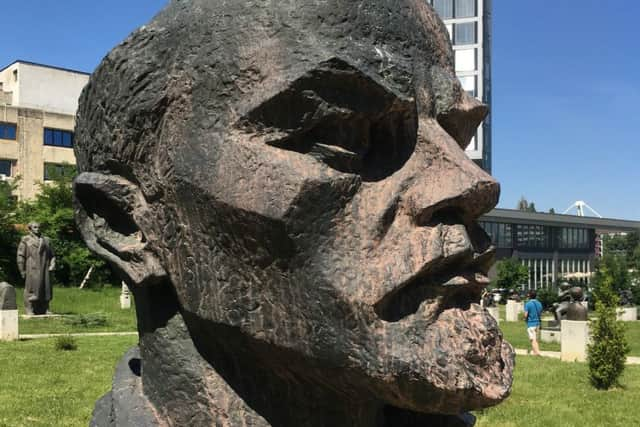

We marvelled at the beauty of ancient cities like Bratislava and Sofia, enjoyed Christmas lunch outside in the warm Greek winter sun, and – this is my personal favourite – stood on the very spot where, in 1905, Lenin met Stalin for the first time, and the world changed forever. The two met in the Workers’ Hall in Tempera, Finland, rather boringly at a conference.

What did I learn on this road trip of a lifetime?

That every country, no, every region, in Europe has its own distinct identity, from tough industrial areas like Wallonia and the Ruhr Valley, to small French and Italian villages where the local cafes serve food worth a Michelin star, but at fast food prices.

Just like here, people rail against the bureaucracy of Brussels. The parliament and its civil servants are seen as too distant and too interested in lining their own pockets to worry about the impact of their policies on young Spanish job-seekers or Latvian pensioners.

There is an almost palpable anger, mixed with fear, at the prospect of mass migration, and a definite whiff of racism in some places.

We saw only white faces in the former Soviet-bloc countries, and were shocked by the number of young African women forced to sell sex in Italian lay-bys.

Yet despite pride in their own culture, anger at a faceless elite and fear of strangers, almost everyone we met was fiercely proud to be European. And very confused, hurt even, that we Brits were turning our backs on them.

It is too easy to dismiss this European solidarity as the inevitable legacy of the horror of the Second World War.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

It is definitely a factor. Everywhere we went we saw poignant reminders of that terrible conflict, from tiny shrines to Greek resistance fighters at the side of mountain roads, to the 2,000 square metres Alsace-Moselle Memorial, just outside Strasbourg, which tells the story of this small French region, “annexed” by the Nazis in 1940.

But there is something deeper at play.

A German friend spoke movingly of his joy the first time he was able to drive freely across the Oder into Poland. And we marvelled at the ease with which we were able to criss-cross the European mainland without having to show our passports.

There appears to be a genuine desire by the people of mainland Europe to build a future together, one based on a single market, freedom of movement and rooted in shared values of democracy, justice and liberty.

A Europe where a young person can plan, with confidence, to study in Florence, work in Bratislava and retire home to Lisbon.

This belief in a shared European future is not confined to the 26 countries on the mainland.

Across the water in Ireland, there is that same sense of a common destiny, and absolute despair at the thought of a hard border between north and south.

We spoke to very few politicians or bureaucrats on our journey. Why would we want to? It is, in part, because of their ineptitude and arrogance that we are facing exile from the rest of Europe.

Even the good ones in Westminster and Brussels, and there are some, grew deaf to the British people’s growing alienation from the European ideal.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is too late for Britain now. There will be no going back on Brexit. The best we can hope for is to stay in the single market and the customs union, but with blokes like Liam Fox and Boris Johnson in charge, I fear a hard Brexit, followed by economic Armageddon, is more likely.

But I hope that European politicians recognise the need for reform. The centrist model, where absolute power lay in the Brussels commission, may have worked in the 1950s and 60s, but it is now as outdated as the manual typewriters the Treaty of Rome was drafted on.

We need a European Union that celebrates regional and national differences, a bureaucracy that is the servant, not the master of the 500 million people it serves.

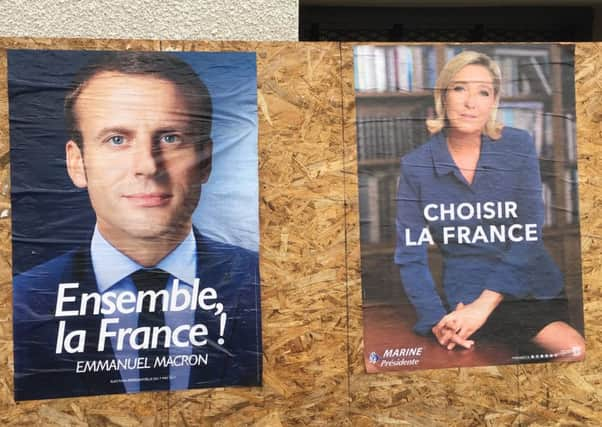

The new generation of European politicians, like the French President Emanuel Macron, understand the need for reform.

His recent call to “give Europe back to its citizens” is one that must not go unheeded by traditionalists such as Juncker and Merkel.

Nor is his vision of a European Union where the UK might “one day find its place again” as fanciful as it may sound.

The darling of the hard left, economist and former Greek Finance Minster Yanis Varoufakis, who is no fan of the EU’s conservative leadership, suggested a few days ago that Britain could, in time, return to its European home.

He said: “You can leave but maintain good links, and potentially come back in if the EU shows it’s transformed itself.” He also said that his “close friend” Jeremy Corbyn, was now of a similar view.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI am not sure I would want to put my faith in Mr Corbyn, a Eurosceptic for much of his career, but I do hope that young pro-Europe politicians, such as Labour’s Ian Murray and Scottish Tory leader Ruth Davidson, continue to campaign vigorously for a sensible Brexit.

And in the years ahead they will build alliances with their European colleagues, at a regional and national level, to secure a new, more perfect union. A union that we might, one day, feel able to re-join.