Independence and Brexit debates should learn from Rwanda genocide – Murdo Fraser

Lesley’s message was a powerful, and timely one. “The genocide did not start with clubs and machetes,” she said. “It was many years in the making, and it started with words. It began in subtle ways: discrimination; humiliation and mocking; treating others as less than human; the language of hate.”

She went on to make the point that treating others as less than human leads, in the end, to violence. And if we are to avoid future genocide we need to avoid the factors that lead to polarisation and division, by treating one another with dignity and respect, particularly those with whose ideas we totally disagree.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOver the last few years, we have witnessed the heat of both the Scottish independence referendum, and then the Brexit vote, with a rise in political discord and division, and a country divided down the middle. The “othering” of political opponents is something to which we have become accustomed in Scotland in the period since 2014. Hardly a day goes by without the use of insults such as “traitor” or “quisling” being thrown around on social media. To their shame, we have seen leading figures in nationalist parties like UKIP and the SNP tacitly, or even explicitly, encouraging such language, by questioning the loyalty of those who take a different view.

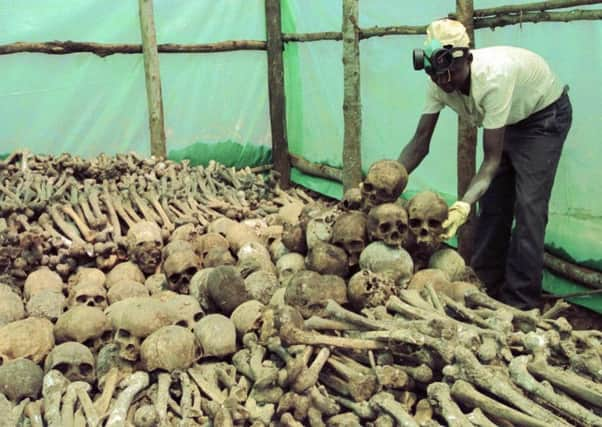

Some political issues are by their very nature divisive, but that does not mean that we cannot conduct a political debate on a respectful basis. We need less division, less discord, more compassion, and more reconciliation. We are fortunate that in modern times we have never suffered the horrors seen in a country like Rwanda, but that does not mean that there are not lessons we can learn from the experience there.