Scottish independence: What lessons can be learned from across the Irish Sea

Market reaction to the Liz Truss-Kwasi Kwarteng mini-budget led to one of the largest drops in the value of the pound in recent history.

In light of these events, the latest Scottish Government White Paper on independence continues to propose the informal use of sterling (“sterlingisation”) before adopting a ‘Scottish pound’ that would be managed by a new ‘Scottish Central Bank’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGiven the recent volatility experienced by the pound, the lack of critical reflection on how the proposed currency would function in the event of similar future volatility is somewhat disconcerting.

Part of the dissonance among voters is regarding the vagueness of these plans – it is unclear how such proposals would logistically work or how credible they would be.

Insight for how the proposed currency arrangements could and, more importantly, do work can be gleaned through examination of Ireland’s experience navigating these very same issues since independence from the UK in 1922.

Given the pound exchange rate is now viewed as a barometer of success of UK Government economic policy, such insight would be key for designing credible institutions to navigate independence in Scotland.

Currency regimes

Over the century since independence, Ireland has had five currency regimes: “Sterlingisation” for the initial years of independence (1922-26); a one-for-one peg with pound sterling (1927-79); a multi-country adjustable peg system known as the European Monetary System (EMS) (1979-93); a brief floating currency (1994-98); and membership of the Euro (1999 to present).

Therefore, unbeknownst to the man on the street, in the 100 years of political independence the country has only exercised ‘monetary independence’ for less than a decade.

Similar to the latest Scottish Government proposals, at the onset of independence the Irish Free State did not create a separate currency, and as the Economist gleefully reported in 1923, it “was in no hurry to establish one”.

The early years were effectively “sterlingisation”; sterling continued to be the de facto currency with no attempts to change the status quo ante.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

As Joseph Brennan, a key architect of Ireland’s post-independence fiscal and monetary institutions, later reflected, this was out of "practical necessity” given the turmoil of the time, “as legislation on so vital a matter as currency would probably have created public alarm”.

A central bank was not established immediately upon independence. Irish officials were hesitant to institute any sweeping reforms to the existing monetary system since Ireland had been part of a monetary union with Great Britain since 1826, with the Bank of England acting as a central bank.

The Irish government established a commission of inquiry into banking and currency in March 1926 that was purposefully chaired by an external (i.e., non-British) financial expert.

The chosen expert was Henry Parker-Willis, a professor from Colombia University, who had experience in the establishment and working of the US Federal Reserve system.

The other members of the committee were representatives of key stakeholder groups – banks, the business community, and civil service. This is one area where the Scottish Government could garner credibility and confidence, by following the precedent of establishing a transparent, independent, and non-partisan commission of inquiry.

The two major recommendations of the Parker-Willis committee are similar to the latest SNP White Paper proposals – the committee recommended a sterling peg because of the historic trading links with the UK, but crucially recommended revisiting the sterling link if Ireland’s trading patterns were to someday change.

The other recommendation was the establishment of a body to regulate currency. The Irish Currency Commission – effectively a currency board – was modelled on the US Federal Reserve system with a primary role to manage the peg.

It aimed to serve and evolve with, rather than alter, the existing monetary system.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy 1943, Ireland had converted its currency board into a central banking organisation. The transition was nominal as the new central bank did not expand its activities materially beyond those of a currency board until the 1970s.

Importing Inflation

Two other aspects of “sterlingisation” that are relevant for future debates in Scotland relate to inflation and the exchange rate.

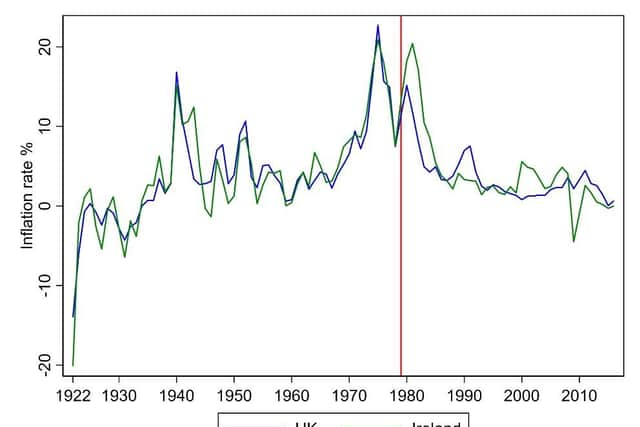

The close relationship between the UK and Irish currencies was reflected in contemporary inflation rates. Set against the backdrop of the instability and hyperinflation of the interwar years, Ireland’s monetary stability should be celebrated, although the continued adherence to the sterling peg deserves most of the credit here.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, Irish authorities became increasingly concerned the weakened pound would mean UK inflation would be imported into Ireland.

By 1978, Irish officials were increasingly in favour of joining the EMS with one perceived benefit being a reduction in inflation.

When the sterling link was finally abandoned in 1979, contemporaries expected the punt would increase in value against sterling. There was an associated concern regarding the consequent ‘adverse effects on the balance of payments and foreign reserves’.

Conversely, the punt actually lost value against the pound on floating, as the latter gained value due to North Sea oil and deflationary policies pursued in the UK.

It was not until the 1990s that the punt strengthened against sterling. While breaking the sterling link was fortuitous in providing Irish exports with a competitive advantage, it initially coincided with higher inflation in Ireland in the early 1980s.

Fiscal constraints

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOver the years, UK monetary policy was also a constraint on the Irish government’s budget. The political temptations to engage in fiscal stimulus were strong from the outset, set against the promises of independence and sizeable debt relief, but maintaining the peg required fiscal discipline.

Although in theory the Irish government was free to decide how to tax and spend, the need to maintain the sterling peg prevented various Irish governments from deviating too far from the UK’s approach.

While modern readers are familiar with Ireland’s difficulties associated with the 2007-08 financial crash, an episode from the sterling peg years (1927-79) is more illustrative of the challenges inherent in the Scottish Government’s “sterlingisation” proposals.

One of the defining post-war events in Irish economic history was a disastrous monetary experiment in 1955.

The Central Bank of Ireland experimented with declining to raise its rate of interest in line with the Bank of England, as had been tradition. This led to ‘capital flight’ and the end result was a devastating balance of payments crisis and, in 1958, the highest levels of emigration since independence were recorded.

When rates were realigned, a ‘draconian’ fiscal response was employed to rectify the trade balance.

The episode highlighted the importance for a small, independent region to monitor external balances within a currency union.

It also provided a painful example of internal devaluation via fiscal austerity as a means of rectifying such imbalances. Fifty years later, however, the painful lesson was long forgotten in Ireland.

What lessons can be drawn from the Irish example?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor 50 years, the sterling link was widely accepted as being in the best interests of the Irish economy. It has been argued the contrast between the instability of the ‘floating’ exchange rate (between 1979 and 1998) and the stability of the sterling peg consolidated support for the adoption of the Euro in Ireland from 1999, and the Euro continues to have widespread public support.

As a small country highly integrated with its nearest neighbour, Ireland could not have exerted monetary independence had the option been open if such policy did not mirror the UK’s, as evidenced by the 1955 crisis.

The sterling link provided price stability, but it remained controversial, perpetuating Irish trading links with a sluggish post-war UK economy, yet maintaining the sterling peg placed considerable constraints on fiscal policy and effectively kept the Irish economy tied to the fate of the neighbouring isle.

Ultimately though, as Patrick Honohan reflected, "the choice of currency regime is less decisive for economic performance than is often supposed”.

While an independent Scotland may wish to set up an independent central bank , the Irish experience suggests that adopting a de-facto central bank, with a flexible currency board style arrangement, may be a more suitable approach.

Such an approach shields policy makers from certain political pressures, while offering the credibility and policy space to alter the regime, when the composition and volume of trade warrants.

- Eoin McLaughlin is a professor of economics at University College Cork in Ireland. He was a guest on The Scotsman’s podcast series How to be an independent country: Scotland’s Choices.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.