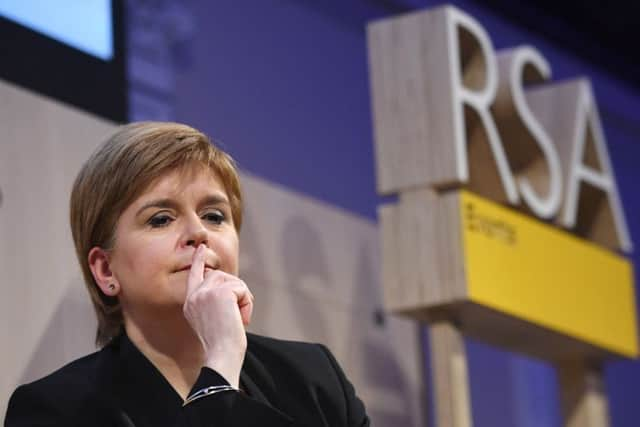

Paris Gourtsoyannis: The problem with Nicola Sturgeon's Brexit plan

Nicola Sturgeon has won considerable praise for the calibre of her leadership in the two-and-a-half years since the Brexit vote. Much of it has been well deserved.

Because she carries so much more authority and credibility than many of her political opponents on this island, her missteps have been forgiven or forgotten.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe miscalculated badly in the immediate aftermath of the Brexit vote, assuming that it would boost support for independence when in fact, wary voters retreated deeper into their constitutional positions.

It also remains an open question whether she was right to weaponise Unionism so dramatically in the final leaders’ debate of the 2017 general election, by claiming Kezia Dugdale privately said she supported a second independence referendum.

By and large, however, Sturgeon has been judicious in her language, cautious in her strategy, and honest about the realities of the impossible position the UK finds itself in – rare qualities, these days.

That’s why her speech in London yesterday was so interesting, because in a few key ways, it departed from type. The Scottish Government trailed it as the presentation of a “common sense” alternative Brexit strategy in contrast to the reckless gambling of both the UK Government and the Brexiteer Tories and DUP snapping at its heels.

In fact, Sturgeon set out what amounts to an audacious gamble, in which the odds of success are, by any objective measure, less that 50:50.

The First Minister couched her speech in familiar measured tones and sound analysis. A no-deal Brexit would be hugely damaging for UK businesses and citizens. The Prime Minister’s preferred Brexit, as set out in her Chequers plan, wasn’t as bad, but still wasn’t any good: it left the mainstay of the UK economy – services – cut off from the EU market.

More to the point, as Sturgeon put it bluntly: “Whatever it is that the House of Commons comes to vote on later this year, it will not be the Chequers proposal.”

Going out of her way to be constructive, the First Minister said that even though she thinks it’s wrong for Northern Ireland to get ‘special status’ within the single market while Scotland leaves with the rest of the UK, the SNP won’t stand in the way if that’s the price of preserving the Good Friday Agreement. With that statement of responsibility alone, Sturgeon set herself apart from the bulk of Brexiteers, Tory and Labour.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe least worst solution, as Sturgeon has consistently concluded, is for the whole UK to stay in the single market and customs union. But she then made two contentious claims.

The first was that her preferred Brexit outcome would mean the UK “would no longer have to be part of the common agricultural and fisheries policies” – the latter of which the SNP has long said it would seek to renegotiate as an independent EU member state. No state in Europe currently enjoys these terms.

It should also be recalled that the SNP would want an independent Scotland (re)joining the EU to avoid the requirement to commit to using the euro, at least initially. I was in Brussels last week to speak to senior EU figures, and asked whether the SNP vision for Scotland in Europe was realistic. That’s not any member state we recognise, came the reply.

The second claim was that voting down the Prime Minister’s Brexit deal offered a chance – indeed, the “only chance” – to get that ‘least worst’ deal which Sturgeon has been pushing vainly for two years. But how? The SNP’s Westminster leader Ian Blackford has spoken about trying to take charge of the parliamentary process when it comes to a ‘meaningful vote’ on the Brexit deal, but hasn’t explained the means to achieve that.

Even if he could, the vote is on an agreement with the force of an international treaty, and changing the words of a motion at Westminster doesn’t change the text in Brussels. Most importantly, this is not how the EU sees it. There are certain things that Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty doesn’t make clear – for instance, can the UK unilaterally change its mind and stay in the EU? – but it is explicit that any withdrawal agreement has to be approved by a two-thirds majority of the 27 EU member states, and a majority of the European Parliament.

If MPs vote against the only deal negotiated between London and Brussels, what would be left to approve? And how would there be enough time to negotiate something new before March 29, 2019? Again, in Brussels I asked whether there was a route to restarting negotiations after rejection of the Brexit deal by Westminster. The only answer is that without the agreement of MPs, there is no deal.

Another reason why Sturgeon’s plan has awkward implications is that it relies on her political rivals. The SNP leader might help rally enough opposition to vote down May’s Brexit deal, but putting something new on the table almost certainly needs a new government – a truth that lurked in the wings during Sturgeon’s address, unspoken.

Sturgeon can’t guarantee that the next leader of the Conservative Party would be a reasonable Remainer but, instead, Boris Johnson – and she can’t sort out Tory party discipline, either. Nor can the First Minister force an election that puts Jeremy Corbyn into Downing Street. Unless the Labour leader offers the SNP another independence referendum, it isn’t even guaranteed that the two parties could do a deal at Westminster after a snap vote.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSturgeon is right to point out that the UK Government, having spent two years arguing that no deal is better than a bad deal, can hardly turn around and warn MPs they’re endangering the economy by voting down May’s Brexit.

But if entertaining a no-deal Brexit is risky, then so is voting against the only deal on offer – because once that decisive step towards the cliff edge has been taken, it isn’t clear that the UK can turn around.