Paris Gourtsoyannis: Give gold medals their proper value

It’s a level of success that is making some people, with typical British modesty, a bit uncomfortable. The fact that Team GB looks likely to split China and the USA on the Rio medals table puts beyond doubt the UK’s status as a sporting superpower.

But is that what the UK wants to be? The unprecedented success of the country’s Olympians at an overseas games has raised questions about the level of investment in elite sport, which in the four years leading up to Rio totalled £274.4 million.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s a huge amount of money, and many, including my colleague Martyn McLaughlin, have rightly asked what we get for it all. Public money – whether it comes from the exchequer or from the National Lottery, as majority of UK Sport’s budget does – is finite, and spending it is about priorities. Many argue that some of that money should be spent at the grassroots, so that more people can take actually take part in sport rather than watching it on TV.

Much of that criticism springs from disappointment that the Olympic legacy of health and well-being we were promised after London 2012 never materialised. It’s only in recent decades that multi-sport mega-events like the Olympics have been weighed down with enough expectation to make a Armenian dead-lifter faint.

The blame rests with the brilliance of Sebastian Coe in securing the Olympics for London in the first place. Sydney was an all-Australian party. In Athens, the Games returned to their spiritual home – leaving a fantastic built legacy that Greece soon found out it couldn’t afford. Beijing announced the start of the Chinese century.

But it was Lord Coe’s genius in taking a group of children from the east end of London to lobby International Olympic Committee delegates and convince them that the Games would transform their lives and communities through sport.

It raised expectations that every subsequent Games would regenerate a city, raise the horizons of a generation of underprivileged youth, and inspire us all to take up sport for the first time.

Of course it never happened, but the balance between elite and grassroots sport isn’t a zero sum game.

Building a genuine Olympic legacy may require different choices, but there are better places to start than UK Sport’s elite athlete programme. We can’t expect the Olympics to do a job that belongs to schools, communities and governments – but mainly ourselves.

When it comes to how money is spent, grassroots sport has much more to do with facilities at a local level, most of which are managed by councils. While Lottery funding has swelled by 466 per cent since 2000, local government budgets have been bled by the SNP in Scotland and butchered in England by the Conservatives.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe impact is clear is obvious across Scotland and the UK: leisure centres and sports facilities have had their hours cut, and each council budget round brings increasingly dire warnings that gyms and pools face closure if the squeeze on funding continues.

Some councils have even cut back on regular grass-cutting and line marking of pitches, despite already charging community groups for their use.

Transferring facilities like swimming baths and leisure centres to arms-length bodies is a near-universal practice, with the share of council funding steadily dropping in favour of service charges for users. Many local authorities are now also passing management of school gyms and playing fields outside term-time on to arms-length organisation so they can charge for their use. You could slash UK Sport’s budget and still not make a dent in the hole made by years of under-funding and neglect.

The answer to the central question about the value of gold is that success inspires. Anything involving the parading of flags will inevitably attract jingoism, but it’s the stories of individuals striving to reach their potential against the odds – sometimes without any funding at all – that make elite sport so compelling.

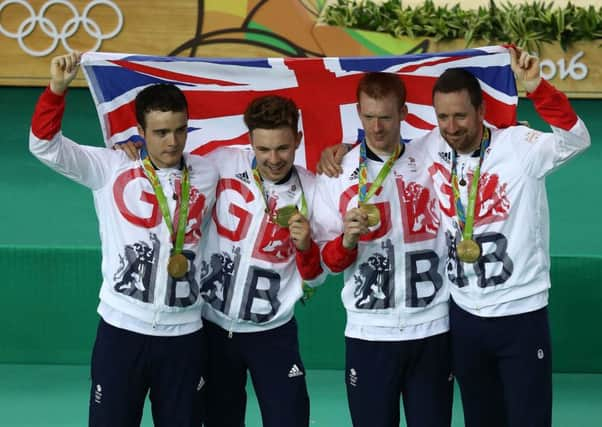

The first anecdotal evidence of the virtuous circle created by Team GB’s success emerged at these games, in a photograph of Bradley Wiggins – who benefitted from the first wave of money into British cycling – with his Athens 2004 gold medal round the neck of a 12-year-old Laura Trott.

Even more remarkable is the photograph of a young Joseph Schooling posing with his hero, Michael Phelps, ahead of the Beijing games. Last week the Singaporean became the only person to beat Phelps in Rio, and won his country’s first ever gold.

No more than anecdotes, of course. Evidence that neither London 2012 nor the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow produced a documented increase in overall sporting participation has been widely quoted.

In fact, sports that did well at London 2012 did see a significant post-Games increase in participation, with up to a quarter of a million more people taking up cycling on a regular basis, and athletics also enjoying a significant boost.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut while greater participation is welcome, on a population level it will not have the same impact as a change in day-to-day physical activity. Cycling is one of the sports that has been pumped full of cash since the advent of Lottery funding, helping to churn out gold medals. Glasgow 2014 left the city the Sir Chris Hoy Velodrome, but that will have a fraction of the impact that a proper cycling infrastructure would. The kind of segregated on-street cycle paths now in abundance in London, New York and Montreal are rarely seen in Scotland.

One sporting jamboree can’t do the slow, painstaking work of changing lifestyles. That should neither surprise or disappoint us. After all, the aim of the ancient Olympics was to bring heroes from warring city-states together in a spirit of friendly competition, observing a truce across the known world.

That, unfortunately, isn’t going to happen either.