Euan McColm: Corbyn's visit forces Sturgeon to pick sides

Remember, for example, the rallies after the independence referendum defeat where thousands gathered, wearing their officially licensed SNP T-shirts, to cheer on the very mention of Nicola Sturgeon’s name. And then there were less joyous gatherings during the 2015 general election when groups of SNP supporters began rounding on Labour candidates in scenes that brought to mind past clashes between rival fans attending brutal local derbies.

This loud and let’s call it enthusiastic support for the Scottish nationalists helped create the impression that the party was unstoppable and that its dream of independence was an inevitability.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo, it was quite the surprise when the SNP lost 21 MPs in June’s entertainingly chaotic elections. And if the scale of the nationalists’ losses was unexpected, even more discombobulating was the revival in the fortunes of Scottish Labour, which picked up six seats and came within touching distance of the SNP in many more. The Scottish Conservative revival under the leadership of Ruth Davidson may have been the big story of election night 2017 but Labour’s success represented the greater shock.

The result of the general election told us that, despite appearances, the SNP was not untouchable. This news came as a particular surprise to nationalist politicians, swept up as they were in the enthusiasm of their supporters.

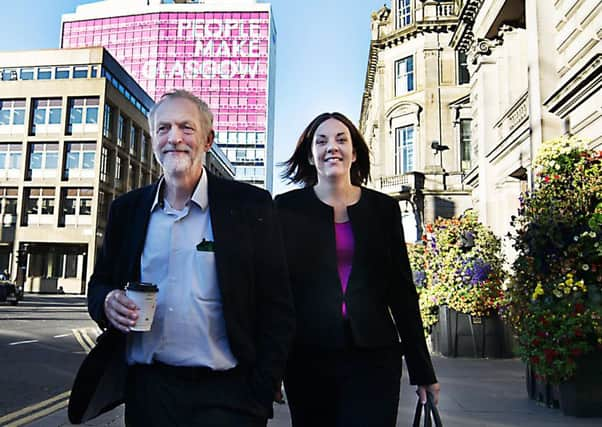

Next month, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn will spend a week in Scotland, travelling around constituencies where the party has the SNP on the back foot. The opposition leader, who many – and I include myself among them – believed was on course to take Labour to a shattering (rather than simply substantial) defeat, is now a bogeyman to the SNP. And it is not clear that the nationalists know what to do about him.

Shortly after the SNP’s second Holyrood election victory in 2011, a senior cabinet source bragged that the party had “built a fortress” on the centre ground of Scottish politics. The joke was on Labour, scrabbling around trying to “out-left” the Nats when what voters wanted was a more moderate, small “c” conservative politics.

Yes, the SNP talked a radical game, but when it came to actions, there was no hunger to scare the horses. Thus, for example, “essential” new powers to raise income tax were not actually used. Having been secured by the SNP, the right to hike taxes was too dangerous to employ. It was one thing to talk loudly about a “fairer” society and quite another to actually do anything about it. The SNP was in no mood to upset those middle class voters who had helped it to power on the basis that it would provide sensible, competent government (a particular line of spin that’s now wearing desperately thin).

The emergence of Corbyn – enthusing, as he has, young voters hungry for change – and the lurch of the UK Conservatives away from the centre have re-established left versus right as a key political battle of our times. Suddenly, the SNP’s fortress on the centre ground looks as if it was built in the wrong place.

Corbyn was not Scottish Labour leader Kezia Dugdale’s first preference to take control of the UK party; she is a more moderate figure than he. But, despite some early differences, the two politicians are said to have a surprisingly good relationship.

Dugdale – wisely, if rather cheekily – claimed full credit for Scottish Labour’s successes in June. But while she may have publicly insisted that her party’s fight against the SNP’s constitutional plans was central to what looks like the beginning of a fightback, those close to Corbyn believe he deserves the credit for Labour’s new Scottish seats.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf Scottish Labour is to build on its unexpected general election result, this tension between those who prefer Dugdale’s more moderate politics and those who back Corbyn’s old-school socialism will have to be overcome. During Corbyn’s visit to Scotland in August, he and Dugdale must present the most united front. Some Scottish supporters of Corbyn would dearly love to see Dugdale replaced by a more “pure” candidate, but they should consider carefully their actions before trying to undermine her. For decades, Scottish Labour has shown how party disunity can have the most negative effect.

Inside SNP HQ, there remains uncertainty about how to take on Corbyn. The Nats’ oft-repeated line about Labour being nothing more than “red Tories” might once have resonated with those on the “radical” wing of the pro-independence movement (and by radical wing, I mean those able to convince themselves that socialism and nationalism are comfortably compatible) but it’s hardly a charge that sticks when it comes to Comrade Corbyn, is it?

The SNP has allowed itself to grow complacent. Of course, there has been no end of enthusiastic interventions on why independence is the answer to any and all ills but of more sophisticated analysis there has been none.

Corbyn’s credibility among the radical left presents a substantial problem for the SNP, which will have to decide whether to hold fast in the centre or start walking the walk when it comes to redistribution of wealth.

In transforming itself from a party of “the shires” into a major force in the central belt, the SNP has lost some of its traditional support. The Tories have surged back in rural Scotland and across the North East, where once the nationalists dominated.

Having seemingly knocked Labour on to its back in urban Scotland, the SNP finds that those vanquished “red Tories” have a new fuel in their tanks.

Just a few weeks ago, the First Minister appeared to be in complete control of our national political debate, now she faces serious opposition from both right and left.

Jeremy Corbyn is able to connect with left-wing Yes voters in a way that no Labour leader has been able to since the establishment of the Scottish Parliament in 1999. The last thing Nicola Sturgeon needs right now is him bringing his own team of enthusiastic supporters to her pitch.