Dani Garavelli: Truth about miners could still save lives

Much has been made, since the inquest jury gave its unlawful killing verdict, of the way in which South Yorkshire police demonised Liverpool fans at Hillsborough while covering up their own mistakes; the way it created a false narrative of the tragedy that persisted long after the truth was obvious. But the culture that made it possible for them to lie with impunity had been fermenting for years – from the fit-ups of numerous IRA suspects in the mid-70s onwards – and only began to be challenged after the Birmingham Six had their convictions quashed in 1991.

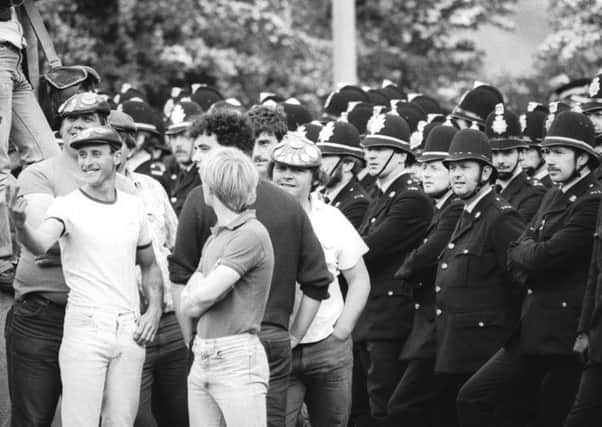

Arguably, it reached its apotheosis during the miners’ strike, when thousands of officers were drafted in to confront demonstrations at pits and at coal-dependent plants such as Ravenscraig steelworks, Hunterston Ore terminal and Orgreave cokeworks. Police (and politicians and newspaper editors) already understood their power to control the story; so the miners were portrayed as a collective threat to national security, while the police were heroes risking their lives to keep the rest of the country safe. In that context, it wasn’t hard to persuade people that the pickets were spoiling for a fight and that the officers merely acting in self-defence.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe extent to which the Battle of Orgreave – the bloodiest confrontation of the dispute – set the template for Hillsborough, however, is only now being properly understood. In 2012, a BBC documentary suggested officers had colluded in writing court statements exaggerating the aggression of the picketers (charges against 95 of them were dropped after police evidence was discredited). A heavily redacted IPCC (Independent Police Complaints Commission) report conceded this was probably true, but said too long had elapsed for anyone to be brought to book.

Now, the Yorkshire Post, which has seen the unexpurgated version, says the same senior officers and solicitor were involved in both events, fuelling suspicions that – under pressure – the force fell back on tactics that had proved effective five years earlier. If the miners at Orgreave could be passed off as violent trouble-makers, why couldn’t Liverpool fans be drunken thugs who caused the fatal crush? Had the handling of the Battle of Orgreave been thoroughly investigated and recommendations acted on, then the Hillsborough cover-up might never have happened.

The fact that the families of the 96 have succeeded, in the face of almost impossible odds, in forcing the establishment to acknowledge the truth gives hope to those seeking the same for the miners at Orgreave. With prominent voices such as shadow home secretary Andy Burnham backing their campaign, a public inquiry might finally be within their grasp.

That Orgreave is subject to scrutiny is important, no doubt. Though the falsely accused miners were compensated, no officers were charged, though some were suspected of having committed perjury. Nor has the suggestion that the picketers were lured into a field so they could be charged at by the cavalry been interrogated in court.

But an inquiry into Orgreave alone is too narrow. Neither the culture that allowed for the fabrication of evidence nor the enduring distrust of the police it engendered was confined to South Yorkshire. And the unanswered questions about the way the strike was handled extend way beyond the English county. As Scottish politicians have pointed out, more picketers were arrested at Hunterston and Ravenscraig than at Orgreave and many still have outstanding convictions.

Some of the issues that ought to be addressed run deeper than the handling of individual demonstrations. Were soldiers secretly deployed? How widespread was phone-tapping? And why was the Tory government allowed to use the police to further its own political agenda?

And yet we mustn’t allow the focus on the 1980s to divert us from what’s happening right now. Though it’s true new restrictions over the questioning of suspects and new technology such as smartphones and ESDA tests make cover-ups more difficult to carry out, the temptation to close ranks when something goes wrong has not disappeared. Nor has the tendency to see protesters as the enemy, otherwise forces wouldn’t have sent undercover officers to infiltrate environmental groups (a practice that is now the subject of another public inquiry).

A year after the death in custody of Sheku Bayoh, a statement issued by solicitor Aamer Anwar last week on behalf of the dead man’s family accused the force of encouraging the press to portray him as drug-crazed and knife-wielding and putting its own interests before those of the family (the case is being investigated by the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner and will also be the subject of a Fatal Accident Inquiry). Meanwhile, Police Scotland’s Counter Corruption Unit was hit by scandal after it emerged it had broken new spying rules to obtain details of a journalist’s sources.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA public inquiry into the miners’ strike (with prosecutions if appropriate) is necessary not only so we can close the door on a terrible chapter in the history of British policing but also to remind the officers of today that if they lie to cover their own backs and the backs of their colleagues, they will be held accountable, however long it takes.